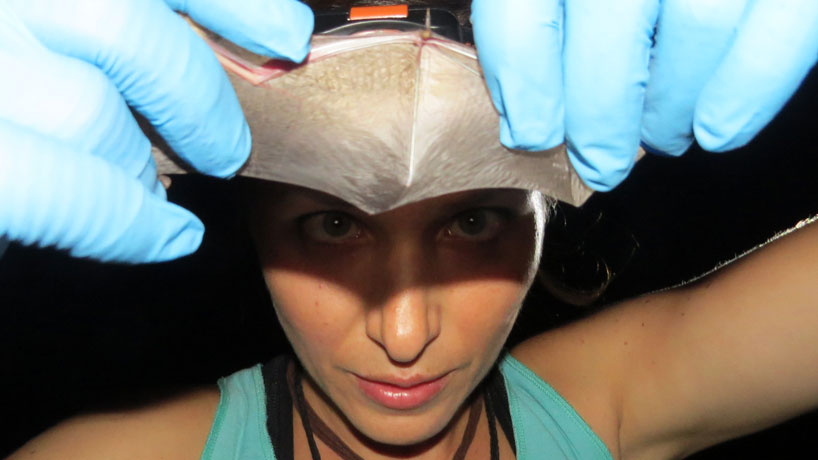

Vona Kuczynska, a threatened and endangered species specialist for SCI Engineering, examines a big brown bat’s wing for damage. She graduated from UMSL with a master’s degree in biology in May. (Photos provided by Vona Kuczynska)

When Vona Kuczynska says she goes to work, she means she hikes around wildlife areas in the night with a headlamp looking for bats.

“It’s scary,” the University of Missouri–St. Louis alumna says. “First of all, it’s pitch black, really far removed from city lights, and a lot of times you trip and fall over logs, run into snakes or hear weird noises out in the woods.”

Kuczynska, who earned her master’s degree in biology in May, is a threatened and endangered species specialist for SCI Engineering, a consulting company hired by developers to make sure their projects abide by the Endangered Species Act.

Kuczynska holds a Mexican free-tailed bat, which she says is not native to Missouri and must have gotten lost.

It’s a job she feels strongly about. Every day Kuczynska helps protect wildlife, including birds, insects, amphibians and endangered plants. But bats are her specialty.

“If I capture bats at a site, I put transmitters on them and track them for seven days,” she says. “We usually try to catch females and their babies because they all sleep in one tree. There can be up to 150 bats in one tree, making up a maternity colony.”

She says it’s a headache for the developer when she locates a colony.

“We can’t relocate bats, so sometimes developers have to stall their projects and wait to clear the trees until November, when the bats have left to hibernate in caves for the winter” and the construction is no longer likely to harm them.

For Kuczynska, it’s important work because all animals have “innate value.”

“I think they have just as much of a right to be here as we do,” she says. “If we can protect them and bring them back out of endangered status to healthy population levels, then we should.”

On record there are 14 bat species in the state of Missouri, and on a typical day Kuczynska says she observes about four to five of those.

“The ones I’m always looking for, and the ones that are the biggest concern, are the Indiana bat, the northern long-eared bat and the gray bat,” she says.

Ever since she was child, Kuczynska knew she wanted to work with wildlife, but she stumbled upon her love of bats helping a wildlife biologist with research.

“I will never forget when I removed my first bat from a net,” she says. “It was such a deciding moment when I held it in my hand, like this is what I want to do.”

So when she was looking for graduate programs in St. Louis, it disheartened her that at the time, none had professors specializing in bat research. But at UMSL, she found Bob Marquis, professor of biology and director of the Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center, who was happy to take on his first graduate student specializing in bats.

“He was so open-minded about letting me do what I wanted,” Kuczynska says of her former adviser.

Marquis specializes in animal/plant interactions, so Kuczynska’s project looked at how invasive plant species, like bush honeysuckle, displace native plants and the insects that depend on them, effecting bats that rely on those insects for food.

“What we discovered was that where there is honeysuckle, there is less bat activity because structurally, the honeysuckle leads to dense bushes and thickets that don’t leave room for bats to fly through.”

Two Harris Center scholarships funded the project: the Leo and Kay Drey Scholarship and the Peter H. Raven World Ecology Research Scholarship.

Before Kuczynska graduated, she already had her position at SCI Engineering. She also landed a part-time position with Titley Scientific, a company that specializes in bat acoustic monitoring, which had her conduct bat surveys over the summer.

During surveys, Kuczynska left bat detectors out in the woods that recorded ultrasonic calls produced by bats. The bats make calls and listen to the echoes they produce to “see” their surroundings and also to locate insect prey.

“Their calls are very loud, actually, if people could hear them, and they carry far,” she says. “You can tell a lot from a bat call. Different species make different calls, so I determined which species were here and how long they were here for.”

For SCI Engineering, surveys involve “mist netting.”

“We set up these really big volleyball-size nets, but the mesh is really fine,” Kuczynska says. “The bats come around corners and they don’t have enough time to maneuver around them, so they fly into them and get caught.”

Handling bats might seem dangerous, but she says that less than one percent of bats carry rabies.

“As a wild biologist, you get vaccinations ahead of time, so I have my pre-rabies exposure vaccine,” Kuczynska says. “And really, I’ve never actually seen a bat covered in disease the way you see possums or rabbits. People think that bats are going to be the ugliest things, and always the first reaction I get is: ‘Oh, they’re actually really cute.’”