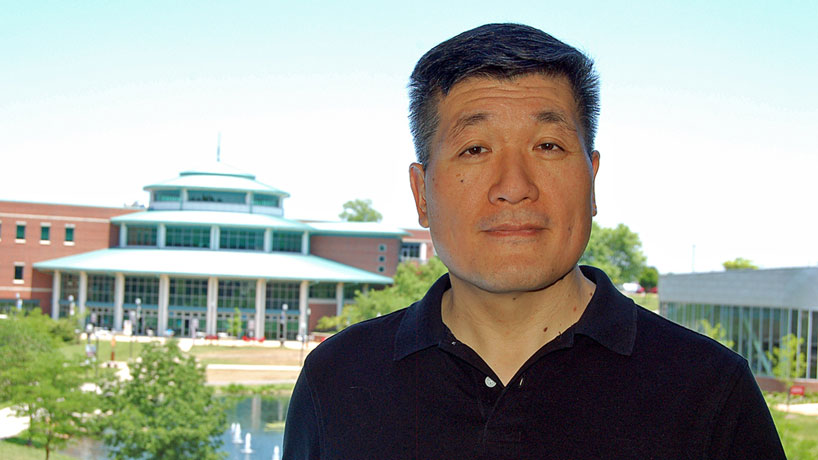

Associate Professor of History Minsoo Kang’s English translation of “The Story of Hong Gildong,” a Korean tale similar to Americans’ Robin Hood, has earned him positive reviews and interviews in The Washington Post, NPR and newbooksnetwork.com. (Photo by Bob Samples)

Do you remember the first time you heard of Superman or Robin Hood?

Probably not – because their tales are so ingrained in American culture that they’ve always just been a part of our consciousness. For Koreans, the character Hong Gildong has similar cultural prevalence, according to Minsoo Kang.

An associate professor of history at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, Kang has just completed an English translation of the classic tale of Hong Gildong, written sometime around the middle of the 19th century by an anonymous author.

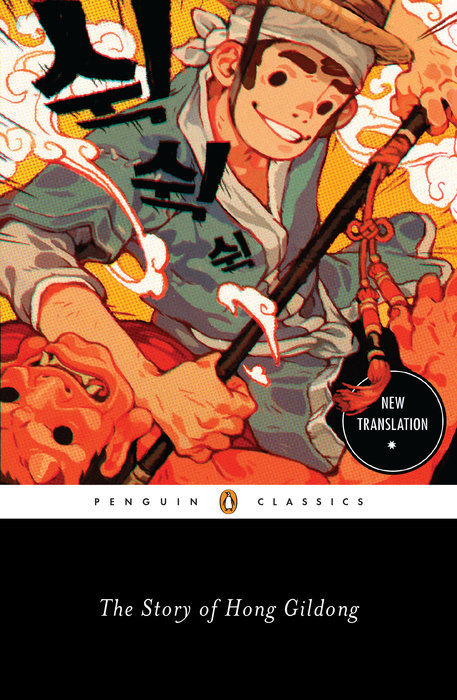

Published by Penguin Classics, “The Story of Hong Gildong” recounts the tale of a child born of a nobleman and female servant. The child is otherworldly talented but not accepted into nobility. Leaving home as a young adult, Hong Gildong becomes a bandit leader who steals from the rich and punishes the corrupt and ultimately establishes a country where he becomes king. Billed as part swash-buckling fantasy, part social protest novel, the tale features assassins, corrupt officials, magic, monsters, romance and vanquished kingdoms.

Published by Penguin Classics, “The Story of Hong Gildong” recounts the tale of a child born of a nobleman and female servant. The child is otherworldly talented but not accepted into nobility. Leaving home as a young adult, Hong Gildong becomes a bandit leader who steals from the rich and punishes the corrupt and ultimately establishes a country where he becomes king. Billed as part swash-buckling fantasy, part social protest novel, the tale features assassins, corrupt officials, magic, monsters, romance and vanquished kingdoms.

Kang’s is not the first English translation of this classic Korean work of fiction, but arguably now the most complete.

“When I was an undergraduate I took a class on cultural history in which I read the great historian Eric Hobsbawm’s book ‘Bandits,’” Kang said. “Hobsbawm showed that the figure of the righteous outlaw, who fights against corrupt and tyrannical authorities and takes from the rich and gives to the poor, is a universal one that can be found in just about every culture in the world.

“While most people immediately think of Robin Hood, I thought of my childhood hero Hong Gildong,” Kang continued. “I ended up writing my final paper on him, using a translation of ‘The Story of Hong Gildong’ that was made in the 1960s by Marshall Pihl.”

Kang said his own translation is based on a Korean manuscript that has a fuller storyline than the one used by Pihl. He said scholars have discovered more than 30 Korean manuscripts of “The Story of Hong Gildong,” with varying plot twists and length. So, he said an English update was in order.

“I think it will be of great interest to English readers both for what will be revelatory to them in learning about traditional Korean culture and literature as well as what will be totally familiar to them in the figure of the righteous outlaw,” Kang said.

Kang’s latest work differs greatly from his 2011 book, “Sublime Dreams of Living Machines,” published by Harvard University Press. From the automaton’s first appearance in ancient myths through the introduction of the living machine in the Industrial Age, Kang’s 2011 book tracks several centuries of robots in Europe.

His latest work, “The Story of Hong Gildong,” has been well received. The Washington Post, NPR and newbooksnetwork.com are among those offering positive reviews and interviewing Kang.

Despite its positive reception, Kang does not foresee using it in the classroom himself.

“I actually am a historian of Europe … so it won’t be used for the regular classes I teach,” he said. “But I have been gratified to hear from both university professors and high school teachers who plan to include it in their courses on world literature. Given the exciting and action-filled nature of the story, it will be a particularly attractive work for younger students.”