Sharlee Climer and colleagues at Washington University in St. Louis and Oak Ridge National Laboratory received a $650,000 grant from the National Institute on Aging to investigate pathways of COVID-19 to better understand why different patients experience different symptoms. (Photo by August Jennewein)

There was something bewildering about news and health reports back in late February and early March about the novel coronavirus that would soon bring normal life across the United States to a halt and – to date – lead to the death of more than 200,000 of its citizens from COVID-19.

Sharlee Climer followed them closely, trying to understand what might be happening.

“We were getting all these reports of all these weird symptoms that people were having,” said Climer, an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. “First, it was respiratory, but then we started hearing about heart failure and renal failure, and neurological problems and all kinds of other things, lethal blood clotting, cytokine storm.”

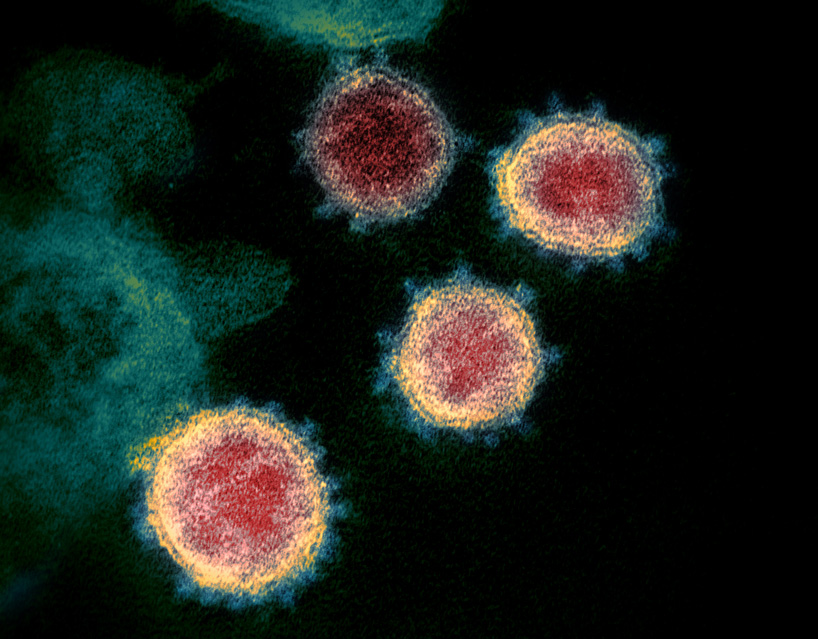

Sharlee Climer is using her skills as a computer scientist to try to better understand Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

She immediately started wondering if it’d be possible to map the pathways of the virus to better understand why different patients experienced different symptoms – and with different severity. She knew doing could help health care providers tailor treatments to minimize the impact of the virus.

Climer and collaborator Carlos Cruchaga, a professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis, have been doing similar work to try to unlock the secrets of Alzheimer’s disease with the support of a grant from the National Institute on Aging. She wondered if the same techniques might also be effective for helping understand the virus.

The two have now applied for and received $650,000 in supplemental funding to find out with a project called: “A Multipronged Interrogation of Large-Scale Omics Data to Reveal COVID-19 Pathways.”

“The supplemental funding application didn’t go out for external reviews like a regular proposal,” Climer said. “The staff has a really quick turnaround, so there were discussions between the program officers and other people at the National Institutes of Health deciding on what to fund.

“Our program officer really championed our supplement. She was very excited about it.”

Climer and Cruchaga will be working with the same collaborators they’ve worked with on Alzheimer’s disease: Alan Templeton, a geneticist at Washington University, and Daniel Jacobson and Michael Garvin, researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. They’ll be mining for combinatorial patterns.

Oak Ridge is home to Summit, the world’s second-most powerful super computer, a valuable tool when examining data on about 5,000 proteins and about 200 metabolites for 350 COVID-19 positive individuals and 150 normal control individuals.

Climer and her lab take a network modeling approach, as with their Alzheimer’s research, to look for groups of correlated proteins and see if they’re associated with different outcomes. They also will use a mathematical programming approach to determine the highest associations between any patterns of proteins and the different outcomes.

Graduate students and research assistants Aaron Heumphreus, Jamie Lea and Kenneth Smith have already begun developing the tools, building on work done by former graduate students Michael Chan, John Brandenburg and Matthew Lane.

One challenge Climer has already overcome was gathering the data. There weren’t data sets from COVID-19 patients readily available when she first started looking into this problem last spring. She was starting to think she might have to build her own, something outside her area of expertise as a computer scientist used to analyzing existing data sets.

But Cruchaga learned of a study already underway at Washington University’s Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, that had been collecting blood, urine and saliva samples from 350 COVID-19 positive individuals who were admitted to the hospital.

They submitted an application to get access to some of the samples and have begun organizing them for analysis.

It could take a couple of months to generate the data, after which they will conduct the analysis to uncover patterns, but Climer hopes at a minimum to find ones connected to cytokine storm.

“I think the cytokine storm was the thing that really triggered me,” Climer said.

Cytokine storm is a severe immune reaction in which cytokines, which play an important role in normal immune responses, get released into the blood too quickly, overwhelming the body in a condition that can become so severe as to be life threatening, leading to multiple organ failure.

There are drug inhibitors that can be used to treat cytokine storm, but it is difficult to diagnose the condition, and using the drugs on patients who aren’t experiencing cytokine storm leaves them with weakened immune systems, more susceptible to the worst effects of a virus.

Helping health care providers recognize it can spare patients serious complications.

Climer is hopeful their research will also prove valuable uncovering the pathways toward other conditions, so that doctors can get ahead of the disease.

This could only be a first step for Climer researching COVID-19. Climer and Cruchaga are planning to submit an application for another, more long-term grant looking at the associations between COVID-19 and Alzheimer’s disease and other effects with aging.