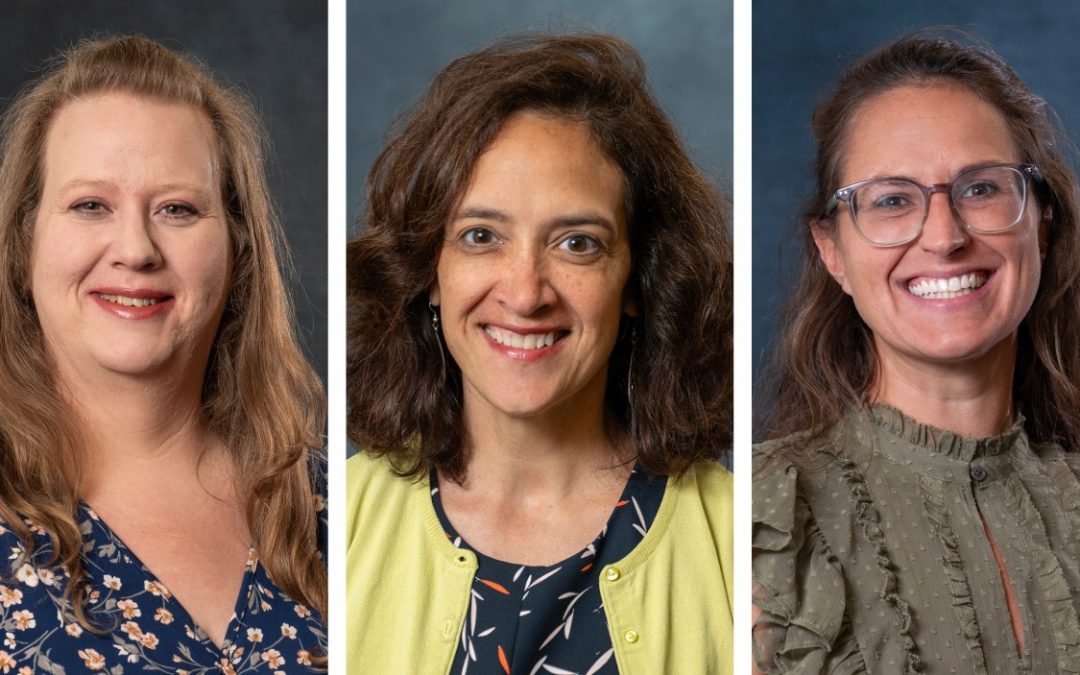

A team of researchers from UMSL’s Community Innovation and Action Center produced a report on the affordability and accessibility of early childhood care across the state of Missouri. They completed their work on behalf of Missouri’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. (Photo by August Jennewein)

One of the biggest challenges facing working parents is finding quality, affordable, dependable childcare.

More than 80 percent of Missouri children ages 5 and under live in a “childcare desert,” defined as an area without enough state-licensed childcare providers. That number increases to 100 percent of the state’s counties when measured for infants and toddlers under the age of 2.

The high cost associated with childcare impacts many families, particularly low-income families despite subsidy programs aimed at offsetting the cost of care. Many parents and early childhood care and education professionals argue that the thresholds to take advantage of these programs are too low, creating a gap in which many families don’t qualify for the subsidies but still can’t afford care.

Those were just a few of the findings in an early childhood needs assessment produced by staff members at the University of Missouri–St. Louis’ Community and Innovation Action Center. They did the work on behalf of Missouri’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education in 2019, and the final version of the report was released last month.

“This really is a workforce issue,” said Kiley Bednar, CIAC’s interim co-director. “Early childhood care supports a strong workforce in our state.”

Wayne Mayfield, associate director of the Institute of Public Policy at the University of Missouri–Columbia, received a $3.5 million from DESE to provide support for Stronger Together Missouri, a federal grant awarded to provide Missouri with the foundation for building a comprehensive, coordinated statewide system of early childhood services. CIAC worked as a partner to produce the needs assessment.

The project began in March 2019. CIAC hired Ben Cooper in April as a health and community data scientist, and he assumed the role of project manager.

Before they began their research, they convened an advisory group of at least 25 early childhood and community leaders from across the state to make sure they were assessing the full range of issues and concerns affecting people involved in early childcare.

“The blessing and the curse of this project was the scope – pretty much anything and everything pertaining to early childhood through age 5,” Cooper said. “We knew there was a large segment of the population being impacted in different ways.”

Bednar assisted with qualitative data, which they gathered through a series of listening sessions, including with childcare providers, families and foster parents from across the state, in cities such as St. Joseph, Kansas City, Kirksville, Columbia, Salem, Springfield, Kennett and St. Louis County and St. Louis city. Community development specialists with MU Extension led some of those sessions and collected data on behalf of CIAC staff.

The project team also conducted multiple one-on-one calls with other stakeholders, including people unlikely attend to the listening sessions. Those included government administrators at the state and county level, and others who worked in special education.

“The one-on-one interviews were really geared at trying to fill in some gaps in information that we needed to include in the report,” Cooper said.

Cooper also took the lead at gathering and analyzing quantitative data, including traditional census data and additional data from state agencies such as the Department of Social Services, the Department of Health and Senior Services and DESE.

They created a series of maps to show how each county compared to the state average and also looked at similar state reports to have a better understanding of where Missouri ranks compared to peers across the country.

In putting together the report, they aimed to focus both on risk but also opportunity. Using a risk-and-reach model, they examined data around uptake of key resources, including percentage of eligible families making uses of programs such as Medicaid and WIC that are already available.

“Missouri’s mixed-delivery early childhood care and education system needs a more integrated, coordinated, and data-informed approach in order to ensure that Missouri’s families have equitable access to high-quality, comprehensive services that support the healthy development of the state’s youngest residents,” reads the report’s executive summary.

Currently, there is too much fragmentation, with different eligibility requirements for programs geared to different age groups. So children who might have access to services when they are 2 might find themselves cut off when they turn 3.

The state also lacks a quality rating system for early childhood care providers. That makes it difficult for families to compare facilities and have confidence in the choices they make for their children. Organizations such as Child Care Aware have helped fill gaps to identify and compare child care options.

“The good news is that the state received an implementation grant, and it is focused on some of the some of the things that came out the planning grant,” Bednar said.

The state already has moved to set up some regional hubs for childcare supports and has created a unified website – https://earlyconnections.mo.gov/ – for all early childhood education related efforts.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has only added to the challenges facing providers and families. Bednar, citing data from Child Care Aware, noted that one in three licensed childcare providers have closed due to the pandemic. There are now eight Missouri counties without any licensed options for families.

The report can be found on CIAC’s website.