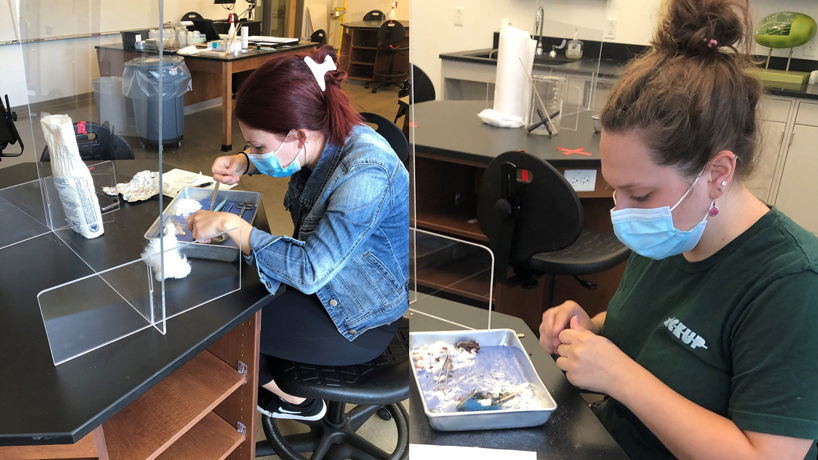

Meagan Thompson (at left) and Sarah Holder were two of four undergraduate biology students to receive research credit for taxidermizing migratory birds during a workshop organized by assistant Teaching Professor Meghann Humphries. (Photos courtesy of Meghann Humphries)

Sarah Holder remembers dissecting a pigeon as a high school student, so she had a pretty good understanding of the bird’s anatomy.

But the junior biology major at the University of Missouri-St. Louis was a little more nervous cutting into the first specimen set in front of her last month on her lab table in the Science Learning Building.

Holder was taking part in a Bird Skins Workshop organized by Assistant Teaching Professor Meghann Humphries. She and 15 of her fellow students had been tasked with taxidermizing more than five dozen migratory birds, preserving their exterior appearance as best they could for future study and use.

“It’s not as hard as it is confusing and daunting,” Holder said, thinking back to her first attempt working with one of the bird’s remains. “It’s not the same as with a dissection where you have to open up everything. You don’t want to make any holes, so you just have to be really careful. It can be tedious, trying to get everything out from inside the body cavity.”

Holder got plenty of practice over the course of roughly two weeks last month as she worked to preserve the skins of 10 different birds through the workshop.

“Most people don’t know what these are, but ornithologists occasionally go to natural history collections – the Field Museum in Chicago has a huge one – and there are these bird skins which have been preserved roughly in the shape of a bird,” Humphries said. “It is just the skin, and it’s stuffed with cotton. We use them for all sorts of things – body measurements but also things like ectoparasites. We can get genetic information from these, so having a good collection is really important.”

Humphries, who teaches a course in ornithology, has had access to a collection at UMSL since joining the faculty in 2019, but it is pretty small and well-worn.

On more than one occasion, she had thought about how nice it would be to update and upgrade the collection for use in her class, but finding bird specimens to use is nearly impossible.

“You have to have a permit to even pick up dead birds because they’re protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act,” she said. “I don’t know why, but the permitting has always been such a problem, and it was probably never going to be something that I could get.”

That’s why it seemed so serendipitous this spring when Humphries received an email from Tara Hohman, a conservation science associate at the Audubon Center at Riverlands and a member of the board at the St. Louis Audubon Society.

The two had first met when Hohman gave a research talk in the Department of Biology last year, and in her email, Hohman let Humphries know that the St. Louis Audubon Society was surveying birds that collided with windows in downtown St. Louis and had permits to collect the remains of those that perished.

“She emailed me and said, ‘Would you be interested?’” Humphries said. “I said, ‘Absolutely.’”

It was only later that she found out she’d be getting between 60 and 80 birds.

Humphries decided to hold the workshop for students interested in learning how to prepare the skins, advertising the free opportunity around the biology department.

“It seemed weird enough that it got my attention,” Holder said.

As an extra incentive, Humphries offered one research credit for undergraduate students who prepared at least 10 skins.

There were 16 students who participated in at least some part of the workshop, which began on June 7 and lasted roughly two weeks. Four of them – Holder, senior Meagan Thompson, sophomore Aria Spencer and freshman Connor Hanneken – did so for research credit.

“I want to go into ornithology with my degree and work on rehabilitation with raptors, so I was very intrigued with the idea of a bird skin taxidermy workshop,” Thompson said. “It was a chance to actually learn more about birds and their anatomy and actually get some credit. We were expected to prepare them in a museum quality way so they could be used and studied by other students later on down the road. I thought that would be really, really neat.”

The experience lived up to Thompson’s expectations.

The students had the chance to work on a variety of different birds, including some regional residents, such as starlings, but mostly they were migrants – including redstarts, ovenbirds, Tennessee warblers, common yellowthroats and several finches.

“They’re following the river, and the lights from downtown disorient them,” Humphries said. “They get lost in those buildings and can’t find their way out, and they end up crashing into windows.”

Thompson said she felt like a coroner sometimes as she worked with the remains because she could see where the damage occurred and have an idea of what exactly happened to them.

The students also had a chance to observe internal differences between species with some having higher fat or more muscle than others.

It usually takes a novice four or five hours to prepare a bird the first time, but both Thompson and Holder said they learned quickly as they went along and had cut that time in half by the end of the workshop.

Both students definitely had their favorites, and for Thompson it was an indigo bunting.

“It’s such a pretty bird,” she said. “I took pictures of all the birds that I did, and it was really gorgeous.”

Holder’s favorite was in line with her hometown.

“Being from St. Louis, I was like, ‘I want to do a cardinal,’ of course,” she said. “We had a lot of the same birds, but we only had a few cardinals, so I was lucky. I got to do a male cardinal, and they’re one of the bigger birds, so they’re a little bit easier to work with. It turned out the best for me, so I really liked doing that.”