Historian John A. Wright Jr. (at right) and his father, John A. Wright Sr., joined moderator Bonita Cornute on stage for “Black in St. Louis,” a discussion of the history of the region and its reverberations today. About 50 people attended the event, organized by UMSL’s African American Alumni Chapter. (Photos by Steve Walentik)

St. Louis has a checkered racial past that continues to reverberate to this day.

Historians and educators John A. Wright Sr. and John A. Wright Jr. – the latter a 1986 graduate of the University of Missouri–St. Louis – have written extensively about the region’s longstanding struggles involving civil rights, with segregation in housing and other policies that have limited socioeconomic opportunity for Black citizens. They’ve also chronicled some of tremendous cultural, political and scientific contributions of African Americans from St. Louis even as they encountered so much prejudice.

A crowd of about 50 people turned out last Thursday night at Century Room C in the Millennium Student Center to hear the two Wrights discuss some of that history as part of “Black in St. Louis,” a Black History Month event held by UMSL’s African American Alumni Chapter.

Retired Fox 2 television news reporter Bonita Cornute served as the moderator for the nearly 90-minute conversation, which Cornute began with a question about the origins of Missouri and the drafting of its state constitution in 1821.

“When the Constitution is drafted, you have a lot of very heavily pro-slavery influence that said that they wanted no free people of color in Missouri,” Wright Jr. said. “They didn’t even want to deal with the Native American population, as arrogant as that seems. However, no free Blacks for sure.”

Congress ultimately rejected attempts to bar free Blacks from living in the state, but the sentiment remained even as a more inclusive draft of the constitution was adopted.

They discussed some of the worst instances of racial violence that occurred in St. Louis in its early history, including the 1836 lynching of Francis McIntosh, who was briefly jailed after an encounter with two St. Louis police officers that left one of them mortally wounded. McIntosh was then abducted by a white mob who tied him to a tree downtown near the present-day site of Kiener Plaza and burned him alive.

“It feeds into the lawlessness stamped on the city,” Wright Jr. said. “So six years later, when there is another high profile case, it is equally as disgusting how the city came out. But instead of burning a person alive, they hanged four men and they advertised, $1.50 if you want to get a ferry out to Duncan’s Island to watch it up close. But most of the city watched from the banks of the Mississippi River. It’s estimated about three-quarters of the city empty out to be able to attend, including schoolchildren.”

A disregard for Black lives and livelihood has continued, even if it’s been manifested in different ways. That includes the destruction of Black neighborhoods such as Mill Creek Valley, which was eliminated to make room for the interstate highway running through downtown, and Robertson, which is now land for the runway at St. Louis Lambert International Airport, as well as Meacham Park, absorbed into Kirkwood.

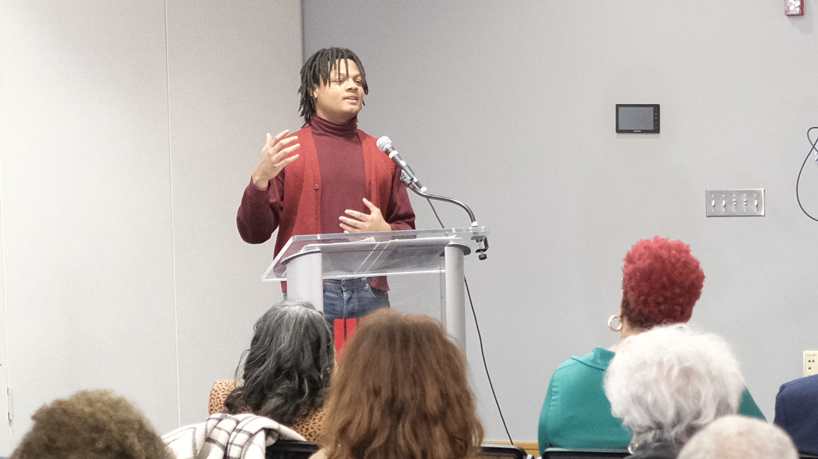

Sumner High School student Stephon Riggins gives a spoken word performance to help kick off the “Black in St. Louis” event, organized by the African American Alumni Chapter.

This isn’t ancient history, as the Wrights made clear, and the struggle for equality continues. That’s not to say there hasn’t been any progress.

“I have to go back to where it was when I was growing up,” Wright Sr. said. “We’ve come a hell of a long ways. We have. When you figure, you couldn’t eat anyplace, you couldn’t live anyplace. We still have a struggle, a long struggle. You’ve got people who want to take us back. In St. Louis, we have to realize how money is made, and by being educated, we can save ourselves. But we won’t be able to do it without saving ourselves.”

He pointed to the declining population in the city of St. Louis and all the vacant land that exists in the central part of the region as problems that must be dealt with. He wants to see more done to restore Black communities where businesses thrive and keep money circulating, improving everyone’s economic fortunes.

The conversation with the Wrights was preceded by a spoken word performance from Sumner High School student Stephon Riggins and the singing of “We Shall Overcome.”

The African American Alumni Chapter was not alone in facilitating a thoughtful discussion for Black History Month. The Black Faculty/Staff Association also held a panel last Wednesday on “Black Resistance: Now and Then,” which aligns with the national 2023 theme for Black History Month.

Tanisha Stevens, UMSL’s vice chancellor for diversity, equity and inclusion, served as moderator for the event, which featured insight from School of Social Work Dean Sharon Johnson, Associate Professor of History Priscilla Dowden-White and E. Desmond Lee Endowed Professor of Urban Education Jerome Morris.

Asked what Black resistance means to her, Johnson said: “For me, it’s about walking in our gifts and our talents and then using our voices in places and spaces where you’re allowed to shine and in those areas where others may not have access. It’s about being a representative in excellence in those spaces where we feel most comfortable and then being brave and bold in those places of discomfort.”

Attendees share a laugh during the Black Faculty/Staff Association Black History Month panel discussion on “Black Resistance: Then and Now.” (Screenshot)

Morris pointed out that the notion of Black resistance is not one that is limited to the United States.

“It’s global in scope, whether it’s anti-colonial movements in Africa, fighting against apartheid in South Africa, fighting for freedom in the Caribbean, in the United States,” he said. “Black resistance is a global phenomenon, and it’s really about affirming African people, Black people, wherever we are in the world on the stating that there is something that we’re fighting against, and that is a white supremacist structure.”

Dowden-White was asked to place Black resistance today in a historical context.

“Comparative questions like this always give me knots in my in my stomach, because each generation has to deal with its own issues, its own concerns and problems,” she said. “But when I think about what it must have been like to have been a slave, sometimes we loosely use that term today to describe the conditions of Black people and others. But to have physically and legally have been a slave is something that I’ve studied, I’ve tried to imagine, but it’s so hard to wrap my mind around what that must have been like.

“From that perspective, we can say that there have been times in the past where we can point to that were harder than what we have experienced since that time. But that being said, I think, especially in our current society, where we no longer have legal slavery, we no longer have legal segregation, but we are still dealing with how the legacy of those things, in addition to the current backlash that we are experiencing to Black freedom in this nation. I think the conversation that we’re having today is really important because we’ve got to be able to identify what is it that we are resisting today.”

View the entire Black Faculty/Staff Association panel discussion here.