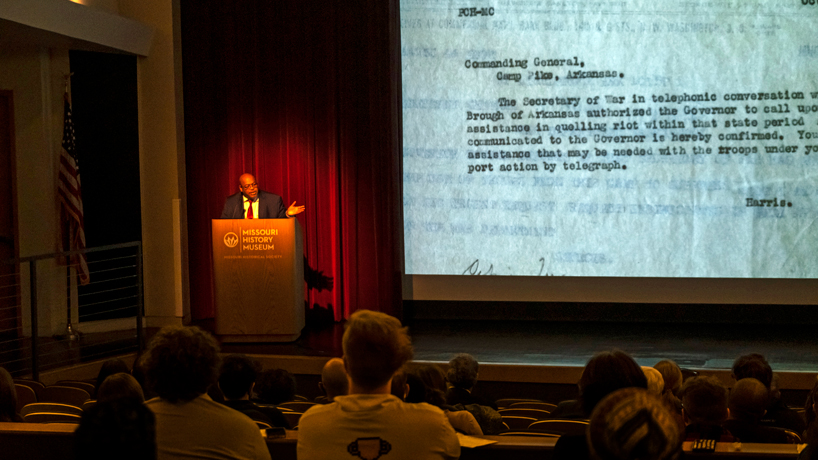

Historian Brian Mitchell delivers the James Neal Primm Lecture in History on “Finding Frank Moore: How Recent Research Changed Our Understanding of the Elaine Massacre,” on March 16 at the Missouri History Museum. (Photos by Steve Walentik)

The Elaine Massacre was the deadliest instance of racial violence in Arkansas history and could well be the bloodiest racial conflict to ever occur in the United States.

Hundreds of Black sharecroppers were killed by white mobs along with federal troops deployed from nearby Camp Pike over three days in and around the town of Elaine in Phillips County, Arkansas, in the fall of 1919. The violence started after a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America at a church 3 miles north of Elaine, at a time when Black sharecroppers sought to push white plantation owners for better payments for their cotton crops.

Like most Americans, historian Brian Mitchell spent most of his life unaware the massacre ever happened, much less its details. That changed after 2005, after Hurricane Katrina forced Mitchell from his home in New Orleans and his work as faculty member at Delgado Community College.

“I found myself moving with my wife to her city of birth, Little Rock, Arkansas,” Mitchell said March 16 while speaking in the auditorium at the Missouri History Museum. “Having little else to do but teach my classes remotely, what I began to do is read books about Arkansas. I came across a book by Grif Stockley, the first edition of “Blood in their Eyes,” and this book told the story of the Elaine Massacre, which I’d only seen in lists that showed all the massacres of the ‘Red Summer’ of 1919.”

Professor Laura Westhoff, chair of UMSL’s Department of History, introduces historian Brian Mitchell at the Primm Lecture on March 16.

That set him off on a path of years of research and discovery about the massacre. Mitchell shared the story of the massacre and some of what he uncovered with the help of his students at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock as he spoke to an audience of nearly 100 people at the 30th annual James Neal Primm Lecture, sponsored by the Department of History at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

Primm chaired the department at UMSL beginning with its founding in 1965 and was later named a Curators’ Professor of History in 1987. He was also a member of the board of the Missouri Historical Society. UMSL established the lecture in his honor in 1993, and he died in 2009.

“It was established to bring distinguished historians to share their current research to a wider public through lectures like this and informal meetings,” UMSL Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Provost Steven Berberich said during opening remarks. “Tonight, we are going to learn about something that I think too many of us didn’t know about. So to have a lectureship that allows us to exchange knowledge and to further our understanding is just a great opportunity.”

Mitchell, who spent more than 16 years as a faculty member at UALR, now serves as the director of research and interpretation at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois,

“Dr. Mitchell’s passion for sharing stories has driven him since he was a young child in New Orleans, drawn to storytelling and history museums and digital platforms,” said Professor Laura Westhoff, chair of the Department of History, while introducing Mitchell.

Mitchell centered his lecture on Frank Moore, a Black soldier who served in World War I. Less than a year after returning home following an honorable discharge, he became one of the “Elaine Twelve,” a group of sharecroppers who survived the massacre but were ultimately charged with and found guilty of killing a white man who died during the clash.

As Mitchell explained, they appealed to the United States Supreme Court in two cases – Moore v. Dempsey and Ware v. Dempsey – on grounds that the mob-dominated trials that resulted in their convictions violated the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. Moore v. Dempsey was decided first, and the Court ruled in favor of the defendants.

Though they initially remained in jail facing retrial, Governor Thomas McRae eventually commuted their death sentences to 12-year prison terms, making them eligible for parole. They were released from prison in 1925, but Moore and the other 11 didn’t remain in Arkansas.

Fearful of being lynched, most fled north and restarted their lives in cities such as Springfield, Illinois; Topeka, Kansas; and St. Louis.

Mitchell and students at UALR conducted extensive research to try to uncover what became of them. They learned that Moore made his way to Chicago, where he found work as a security guard for a real estate company. He died just shy of his 44th birthday in 1932 and was buried in Little Rock National Cemetery. A marker was dedicated in his honor there in 2020.

Mitchell noted that Moore’s story fits in the broader story of the Great Migration, which saw an estimated 6 million African Americans move to Northern, Midwestern and Western States beginning in 1910 and continuing until 1970 as they looked to escape racial violence and pursue economic opportunities away from the oppression of the Jim Crow-era South.

“One of the things that I didn’t realize until I began teaching about Elaine was how many of my students were from Phillips County,” Mitchell said. “I quite literally had hundreds of students from Phillips County. Of those hundreds of students, maybe only five knew anything about Elaine, so they’d never been taught about Elaine. Many of them went home and asked their parents, both black and white, about their experiences and whether they had family members there. Many of them came back to class and said, ‘I found out from my grandmother that my grandfather was involved,’ or ‘I found out that people in my family were killed as a result of this,’ and this is why half of my family lives in Detroit and the other half lives here’ or ‘This is why I have family in Kansas or Missouri.’

“I believe that it’s important for students to know about the past. I believe it’s important that they have accurate depictions of what happened because of sharecropping and a number of other atrocities in Arkansas – the state was able to cover them up, largely because people had forgotten them or there was no knowledge of them or they lived in fear.”