Doctoral candidate Becky Hansis-O’Neill has more than 200 tarantulas in her care as part of her research in Professor Aimee Dunlap’s Cognitive Ecology Lab. (Photos by Derik Holtmann)

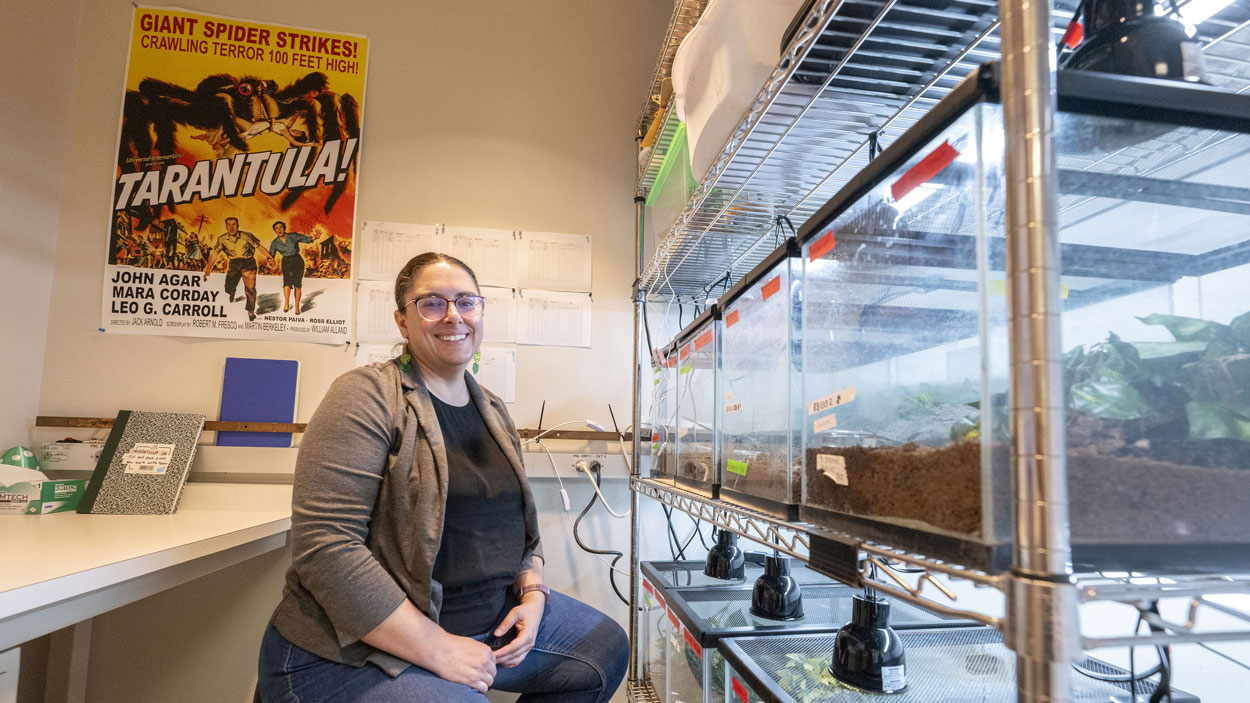

Anyone who wanders into the lab in Room 235 of the Research Building at the University of Missouri–St. Louis will eventually find their eyes drawn to the vintage movie poster hanging on the wall.

It depicts a massive spider terrorizing a town as a woman in a white dress dangles from its fangs.

“GIANT SPIDER STRIKES! .. Crawling Terror 100 Feet High!” blare the words above the image. Across the middle is the title of the 1955 film the poster was created to promote: “Tarantula,” starring John Agar, Mara Corday and Leo G. Carroll.

It sums up a popular – if exaggerated – perception of the hairy arachnids, i.e. that they’re aggressive, scary and a danger to humans. It’s the same reason they’re a favorite lawn decoration alongside ghosts, gravestones and skeletons during October leading up to Halloween.

Becky Hansis O’Neill, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Biology, has developed a much different attitude about the animals. She’ll often use words like “cute” or “pretty” and talks about their unique “personalities” as she shows off some of the more than 200 tarantulas in her care.

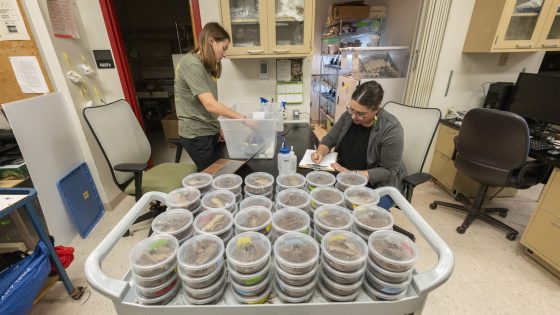

Most arrived on campus last fall as babies, and with the help of undergraduate research assistants in Professor Aimee Dunlap’s Cognitive Ecology Lab, Hansis-O’Neill has been tracking their development while running experiments to test the impact of diet and heat on how fast they grow and how often they molt.

“We really don’t know much about them,” Hansis-O’Neill said. “There are only a few labs in the world that really dig in and work on tarantulas, doing things other than systematics and taxonomies – so looking at different species and evolution and how they’re related. Us learning about their natural history here and their place in their environment is really filling in some knowledge gaps.”

Both the Saint Louis Zoo and the Missouri Department of Conversation have taken an interest in her research.

Working with collections at both UMSL and the Zoo, Hansis-O’Neill has been measuring tarantula heart rates and trying to determine if they increase out of pleasure – say, after eating a cricket – or fear when encountering a new threat in their environment.

She has also partnered with MDC to survey tarantula populations across the state, which rests at the northern edge of their natural range. Though not nearly as abundant as they are in states such as Texas, they can often be found in grassy glades south of the Missouri River.

“We’re examining how their populations increase and decrease,” Hansis-O’Neill said. “One thing I would love to study is what they eat and how much they eat. Do they control grasshopper populations that might overgraze in these glade grasslands? How important are they in their ecosystems? There are all these questions that we don’t know. So, they turn out to be good study organisms.”

A new direction

Dunlap had never done any work with tarantulas before Hansis-O’Neill arrived at UMSL in the fall of 2021. Her preferred study subject has been bumblebees, and she uses them to investigate evolutionary questions of cognition. But Dunlap had no problem with Hansis-O’Neill branching out in a new direction.

“Becky’s interested in the welfare of animals, and in particular animals that we have a hard time putting ourselves into their minds,” Dunlap said. “Welfare has always been an interest of mine because I think there’s a lot of cutting-edge science that happens with welfare and arthropods. It has to do with cognition, but it also bleeds into philosophy and these applied types of questions, and that makes it very intriguing for me.

“Here was a really motivated student that had a very clear vision of what she wanted to do but was also flexible about how it came about and the animals that she would work with.”

When Hansis-O’Neill was still applying to the doctoral program, Dunlap helped facilitate conversations with David Powell, the director of research education at the Saint Louis Zoo, and Ed Spevak, the zoo’s curator of invertebrates. It was through those discussions that Hansis-O’Neill wound up honing her focus on tarantulas because they identified a need to learn more about them.

“There’s a huge gap in our knowledge,” Dunlap said. “They’re all over the world, and they live a very long time – many of those females can live 20 to 30 years. When we see animals that live long, there’s a lot of work in the evolution of cognition that tells us those animals should have more sophisticated cognitive abilities, but I think people think of them as like pet rocks. The fact that there have been so little studied was surprising to me, but it’s also exciting.”

Returning to research

Hansis-O’Neill was eager to re-engage with scientific inquiry. She had earned her bachelor’s degree in psychology and a master’s degree in biology from Idaho State University, where her thesis explored the relationship between mites and beetles.

Doctoral candidate Becky Hansis-O’Neill’s face is reflected in the outside of a terrarium holding a mature tarantula.

But after completing her master’s, Hansis-O’Neill left behind the lab and eventually landed a position more closely tied to science communication. She went to work as a producer for Ideum, a full-service exhibit design and production company based in Corrales, New Mexico, that partners with museums, zoos, aquariums and other cultural and educational centers and specializes in creating immersive and interactive exhibits.

Hansis-O’Neill joined the company in 2017 and earned multiple promotions during her more than 4½ years, eventually becoming director of creative services. Each time, she found herself being pulled a little further away from science as she took on more planning and project management responsibilities. She felt jealous of some of the clients she worked with and longed to get back into research.

“I really wanted to work on invertebrate behavior,” she said. “I wanted someone that would let me work on invertebrate welfare, which is kind of a niche topic.”

Dunlap and UMSL gave her that chance.

The world was still in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic when Hansis-O’Neill applied to the doctoral program in 2021. She and Dunlap had an informal interview via Zoom, and she set up a few conversations with other graduate students to hear about their experiences, but she hadn’t been able to visit campus before deciding to make UMSL her only choice. There was still a lot she didn’t know about the university when she received her acceptance.

An unexpected benefit was the presence of the Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center, for which Dunlap serves as the director. The center is a partnership between UMSL, the Saint Louis Zoo and the Missouri Botanical Garden that provides research support for students as they pursue master’s and doctoral degrees in biology with a focus on ecology and conservation.

“That turned out to be amazing,” Hansis-O’Neill said. “There’s so much more support here for research, for grad students and undergrads, through the Harris Center that is uncommon at other universities. My Harris Center grants were my first grants before I was able to do outside things, and the Harris Center has supplemented projects I’ve started with outside organizations.”

An array of questions

Dunlap has found herself impressed and inspired by Hansis-O’Neill’s curiosity about the natural world.

“It generates a lot of questions, a lot of hypotheses, experimental ideas and ways that we could tackle things, and her solutions are always really interesting and very collaborative and really bring in partners and students,” Dunlap said. “It’s the way she thinks about doing science, and she has the skills to back that up.”

Her early work at UMSL involved the bumblebee populations that Dunlap typically studies as she got acclimated to the lab. She began exploring the effects of caffeine on bee behavior, including whether they learn to seek out the stimulant, which is naturally occurring in a number of plants. In an innovative part of the study, she has used a mass spectrometer to test for the presence of caffeine in the bees’ fecal material.

She soon also started engaging with tarantulas in the zoo’s collection while simultaneously conducting a literature review of previous research involving the arachnids.

As she was doing that reading, she realized that some of what she was learning could be useful to tarantula owners and collectors, and she wound up sharing some information on the Tarantula Collective, a cross-platform social media group made up of hobbyists. That led to a guest appearance on the Tarantula Collective podcast hosted by founder Richard Stewart in 2023. The episode has been viewed nearly 36,000 times on YouTube.

One member of the audience was a tarantula enthusiast from University City named Tim Cusick. After listening to the conversation, he reached out to Hansis-O’Neill to see if he could support her work. He wound up making a donation that allowed her to acquire the 200 baby tarantulas from a breeder in California for the purpose of studying ways to reduce mortality and increase growth of tarantula spiderlings.

Her connection with the Missouri Department of Conservation began because she called to inquire about whether she could collect a few tarantulas for study. She learned that they were protected and that not much was known about the health of the population, so she wound up volunteering to go out and count them across the state.

She is currently working to connect all these projects as she looks to complete her dissertation. She’s on track to defend and graduate this spring.

Called to mentor

Hansis-O’Neill has won plaudits from Dunlap and others for the way she has involved undergraduate students in all aspects of her work. She insists it’s helped her just as much as the younger students.

Doctoral candidate Becky Hansis-O’Neill and junior biology major Jordan Kolinski work to gather and record data from their research on tarantulas in the Dunlap Cognitive Ecology Lab. Hansis-O’Neill has excelled as a mentor to undergraduate students such as Kolinski throughout her time in the doctoral program.

“There are a few really important ways undergrads working with me has benefited me,” she said. “The big one is I can get more done if I train people. I can get more data collected faster, so I can do more complex and bigger projects. The other thing that I did not expect is undergraduates ask a lot of questions. So, there have been parts of my projects that have been developed just based on undergraduate interests or even master’s student interests.”

She shared that the idea to test the bumblebees’ fecal matter for caffeine came after one of the master’s students, in the midst of data collection, quipped, “It’d sure be great if we could drug test them.” That’s essentially what the mass spectrometer has allowed them to do.

“I wasn’t even thinking about that, and now that’s become a really cool thing in my thesis that other folks haven’t done,” Hansis-O’Neill said.

But perhaps the biggest thing Hansis-O’Neill has gained from working with younger students is a new perspective on what she’d like to do after she finishes her degree.

Watching some of them investigate answers to their own questions, excel in presenting their work at the Undergraduate Research Symposium or land jobs after graduation has been one of the most rewarding parts of her time at UMSL. She originally planned to look for work as a consultant, but she’s now applying to postdoctoral programs and eyeing an academic track that will allow her to continue mentoring younger scientists.

“It feels really important to be able to help people at that stage of their life,” she said. “I feel like I’m having a much bigger impact on helping people than I could, say, in consulting. Getting to know people as they’re going through that college experience and growing is really special. Those relationships are really valuable and really fun, and I really like seeing where students end up and how things go for them.”