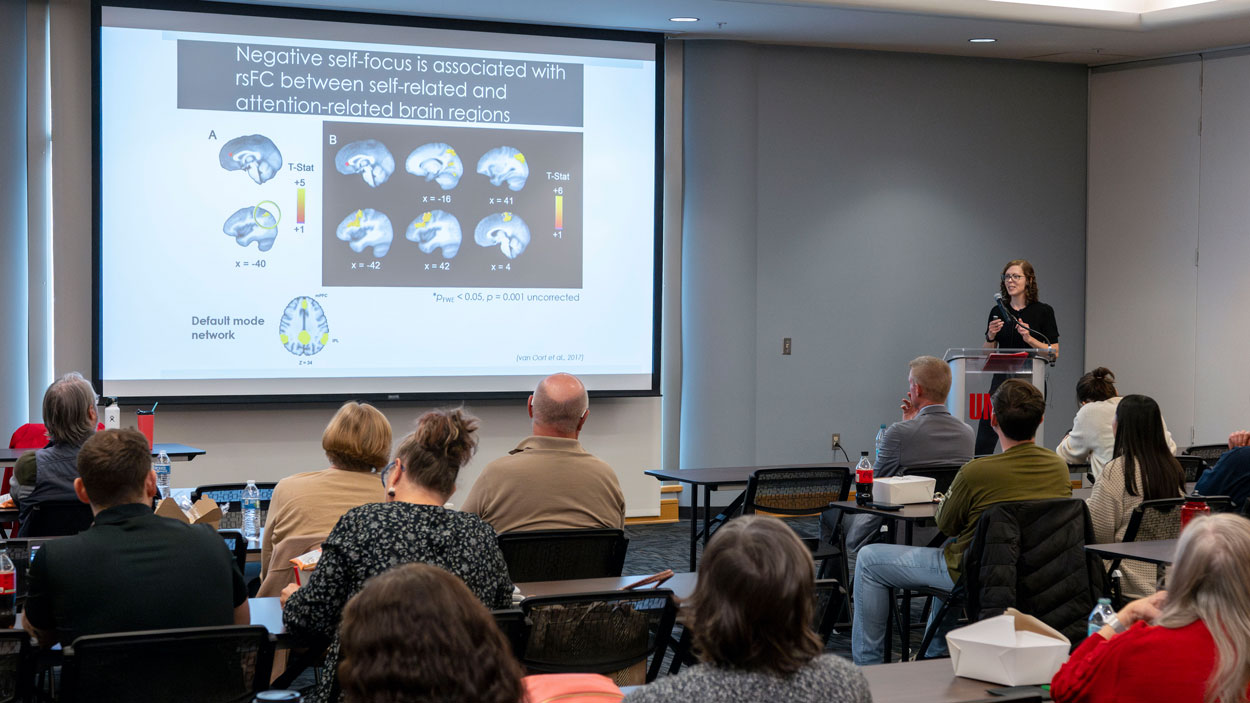

Carissa Philippi is a neuroscientist and associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at UMSL. Her talk for the latest installment of the University of Missouri System’s NextGen Precision Health Discovery Series on Nov. 18 explored how negative self-related thoughts become prolonged and persistent in different psychiatric disorders such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. (Photo by Derik Holtmann)

It’s estimated that adults spend nearly half of every day lost in thought, whether daydreaming, reflecting, planning or empathizing. While driving to work, for instance, you might find your brain drifting to thoughts about a conversation with a loved one the night before or anticipating fun plans for the coming weekend.

These thoughts – known as “self-related thoughts” – occur when one’s attention turns inward to think about their own thoughts, memories, feelings and actions. While everybody experiences these thoughts, they can vary greatly in emotional tone. Some self-related thoughts are positive, but others are inherently negative, leading to rumination, in which thoughts become stuck in persistent, uncontrollable loops of negative self-talk.

Carissa Philippi, a neuroscientist and associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, has devoted her research to studying this phenomenon. As the featured speaker for the latest installment of the University of Missouri System’s NextGen Precision Health Discovery Series last Tuesday, she explored how such negative self-related thoughts become prolonged and persistent in different psychiatric disorders such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“In the current research in my lab, we really take a precision health approach to understand how individual differences in those levels of negative self-related thought might then be represented within the brain,” Philippi said. “Can we identify those neural correlates, those brain patterns associated with negative self-related thought, and can we use that information to then predict why or how people respond to different types of treatment? I’m also interested in determining whether we can further improve well-being by targeting either negative self-related thought through psychotherapy or mindfulness, or target those brain patterns that are important for negative self-related thought through noninvasive brain stimulation techniques.”

Philippi’s lab uses a combination of different psychological measures, such as questionnaires or computer tasks, and brain imaging, including MRI and fMRI technology, to investigate the neural mechanisms of self-related thought. Using fMRI brain imaging technology, for instance, her team observes participants’ brain activity while they rest inside a scanner and let their minds wander. Researchers are then able to observe how the brain’s default mode network – a system of interconnected brain regions involved in internally focused thoughts – functions in both healthy and dysfunctional states.

Studies using fMRI and lesion methods showed that reduced variability in brain activity and altered connectivity within the DMN and attention network are associated with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. When negative self-talk occurs, the brain’s default network becomes hyperactive, and both the frequency and intensity of negative thoughts increase. At the same time, the pathways in the attention network that normally allow people to tune out negative self-thoughts and redirect their attention are impaired, leading to rumination.

“We found that greater negative self-focus was associated with greater communication between the default mode network and the frontal parietal network, or that attention network,” Philippi said. “And so why is this important? Why is this interesting? Well, this is interesting because in healthy individuals, normally, these networks are not positively correlated. They’re not active at the same time. Normally, they are in opposition, so that when you’re thinking to yourself, you’re self-reflecting, usually you’re not paying much attention to the external world, especially if you’re actively engaged in reflecting and vice versa. If you’re actively engaged in something in the external world, then you’re turning your internal dialogue off, right? But in depression, we think, based on these findings and others, that in rumination, there’s an impairment in the ability to shift your attention away from that ruminative self-focus. You’re sort of co-opting that attention network to ruminate, to focus on yourself instead of focusing on the external world.”

Philippi’s findings suggest that negative self-related thought could be successfully targeted through psychotherapy or different mindfulness-based programs, such as rumination-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. These altered brain patterns could also be targeted through treatments that focus on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and research suggests that such treatments are able to change the communication between the default mode network and attention network. In the future, Philippi is interested in investigating how such treatments change how people think about themselves and the potential impact of treatments that target other areas of the brain.

She emphasized that brain structure varies greatly from person to person, highlighting the need for more research to identify precision health approaches that can tailor treatments based on individual brain patterns.

“That’s where my current work is headed – trying to use that precision health approach to understand whether we can measure self-related thought and measure brain activity, so variability in activity and connectivity, to predict who’s going to respond to specific treatments,” Philippi said. “If we’re able to decrease self-related thought or negative self-related thought, we should see an increase in variability in brain activity and normalization in the communication between the default network and that attention network.”