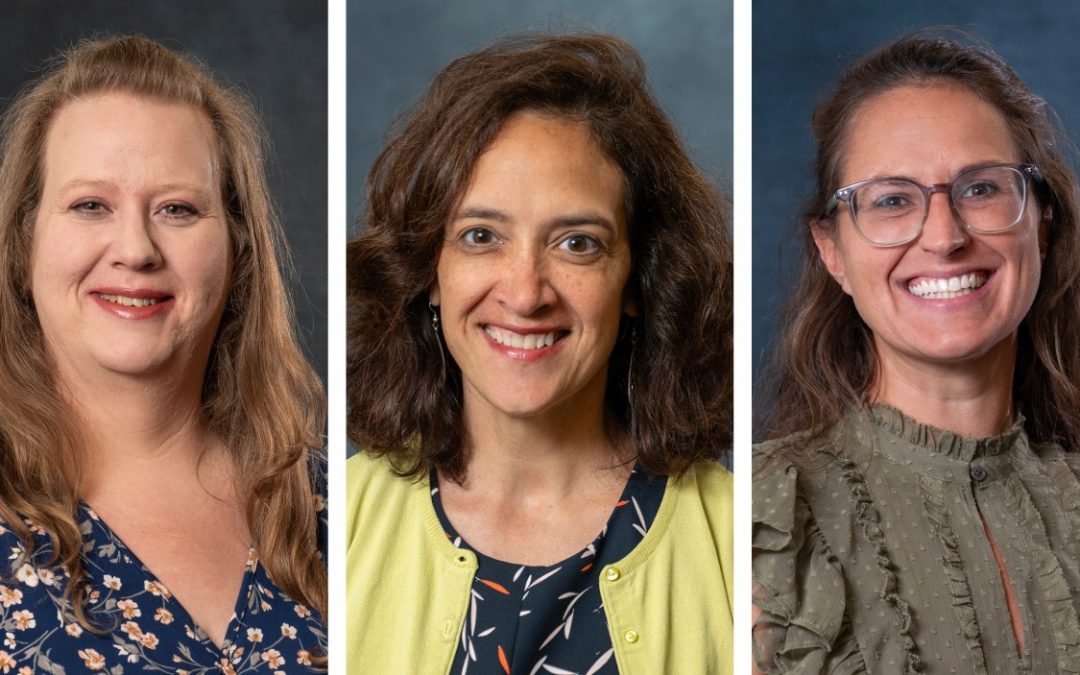

Assistant Teaching Professor Rebecca Polich (at right) points to an image of a human heart while giving a demonstration of the Department of Biology’s Anatomage Table to faculty members (from left) Jilian Bueltmann of the Department of Biology and Michelle Barrier, Paula Prouhet and Cara Doerr from the College of Nursing. (Photos by Derik Holtmann)

Rebecca Polich had an audience of four entranced in early October as she stood at the end of the hallway on the fourth floor of the Science Learning Building at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

Set out before her was the interactive Anatomage Table the Department of Biology acquired last summer in collaboration with the College of Arts and Sciences and College of Nursing, and Polich, an assistant teaching professor in her third year at UMSL, was giving a demonstration of its uses.

Nursing faculty members Michelle Barrier, Cara Doerr and Paula Prouhet along with Jilian Bueltmann, an assistant teaching professor of biology, looked like they would’ve paid top dollar for the front-row view they had for the show. They were captivated as Polich called up an image of a beating human heart on the large table-top screen in front of them and began manipulating it, pulling apart different chambers to get a peek inside, highlighting how blood flows through and demonstrating how conditions such as atrial fibrillation and ventricular fibrillation on a corresponding EKG display.

Assistant Teaching Professor Rebecca Polich adjusts the settings on the Anatomage Table while displaying the skeleton of a pregnant woman during an October demonstration in the Science Learning Building.

Later, Polich called up the image of a pregnant woman, Vicky, an actual body donor who’d been digitally scanned. With a few taps on the touchscreen, she’d peeled away the outside skin and organs and zoomed in on the baby growing in Vicky’s uterus. She rotated the image to reveal different details of the pregnancy.

“It’s so cool,” said Barrier, whose expertise is in maternal child nursing and who spent most of her career as a labor and delivery nurse at Mercy Hospital. “We talk about this, but to actually be able to see it …”

Barrier noted the presence of vena cava syndrome, also known as aortocaval compression syndrome or supine hypotensive syndrome, which occurs when something – in this case pressure from the baby in the uterus, blocks or compresses the large vein carrying deoxygenated blood from the body to the heart.

“You see why,” Barrier said. “It’s right there. See that baby laying on it.”

The nursing faculty members would’ve gladly stayed for hours examining other bodies contained in the table’s library of subjects.

“I’d be playing with it all day,” Prouhet joked.

“You couldn’t get Paula out of the building,” Barrier said amid chuckles. “You’d have to call security to escort her out.”

Polich is hoping students get a similar sense of wonderment as she incorporates its use in her classes, particularly for levels I and II of Anatomy and Physiology, which typically attract more than 100 students combined each semester.

Those courses tend to be populated by students already in or hoping to pursue their BSN in the College of Nursing, though they also attract biology majors and students looking to pursue other medical careers, as physician assistants or as future doctors, dentists or optometrists.

Polich also imagines applications for the table in comparative anatomy or comparative physiology courses.

She’s spent time throughout the semester, usually on Tuesday mornings, playing with the table and trying to understand all its capabilities, but has only deployed it in a couple of her lectures.

“We’ve definitely been ramping it up this semester,” Polich said. “But compared to what I’m hoping to do, I’m hoping to actually have most labs involve this.”

The tables are intended to allow students to practice procedures on real human bodies without the need for physical cadavers. Unlike more traditional models, the images the table displays are not static, so students can more easily visualize and interact with anatomical structures in real time.

“For students, I would say it’s very dramatic,” Polich said. “It can do things that the models can’t. We do dissections in our lab with like sheep hearts, we have eyes, and those aren’t going to be going away anytime soon. But what’s nice about this is all the scaffolding. They don’t have to guess what they’re looking at. I think, if anything, this is a great thing to do first, and then you can open up your sheep heart and start IDing, ‘Here’s my left ventricle. Here’s my mitral valve.’ That sort of thing. I think it’s going to be really powerful.”

Anatomage was founded as a medical device company specializing in 3D medical visualization technology in 2004, and it introduced its first interactive table in 2012.

“The early ones were, as you can imagine, actually not so great,” Polich said. “It’s only been within maybe the last five years, probably not a full decade, that the technology has really been maybe worth it, and they are getting better over time too just like all kinds of technology. It’s coming to a place where it’s easier to get them into classrooms, and what they can offer is truly of value to students.”

Polich, who holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of California, Davis, and a PhD from Iowa State University, believes there is no substitute for studying with actual cadavers. But the table allows students to look inside and get a better sense of the anatomy without having to spend weeks peeling back the layers of the body, and it can show them how muscles function and allow them to see rare cases they might not otherwise have access too.

“I am beyond excited,” Barrier said, “that students will now have this technology to assist in learning about how the body works!”