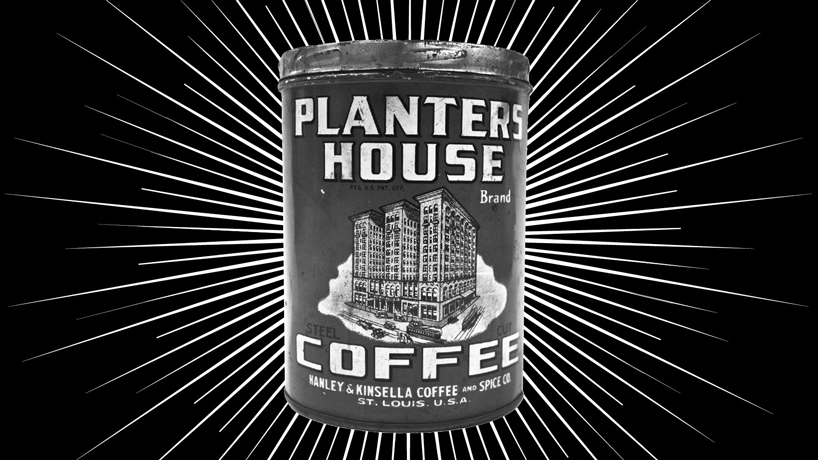

“Why Americans drink coffee: the story of an unlikely romance” is the title of this year’s James Neal Primm Lecture in History, set for 7 p.m. Sept. 14 at the Missouri History Museum. (Coffee image from the Missouri History Museum. Design by Wendy Allison.)

Like many people, Steven Topik’s coffee habit was formed in college. But it’s become a lot more than a caffeine fix to the historian in the years since.

“I experienced coffee as a site of sociability, a drug, an academic subject and a commodity,” says Topik, a professor of history at the University of California, Irvine, who is writing a world history of the popular beverage.

He will discuss it in St. Louis Sept. 14 as a guest of the University of Missouri–St. Louis. Titled “Why Americans drink coffee: the story of an unlikely romance,” his address is this year’s James Neal Primm Lecture in History. Free and open to the public, the event begins at 7 p.m. at the Missouri History Museum (5700 Lindell Blvd).

Leading up to his visit, which is sponsored by UMSL’s Department of History and the Missouri History Museum, UMSL Daily caught up with Topik on all things coffee, history and St. Louis.

Your interest in coffee is obvious given the topic of your upcoming lecture, and the picture of you on the event flier suggests you enjoy drinking coffee as well as writing about it. Is that the case? And if so, how many cups a day do you drink on average?

I drink about two cups of coffee a day. Sometimes a little more.

How did you arrive at this intellectual exploration of coffee and its history?

My interaction with coffee started at home since my father, from Germany, and my mother, from Austria, drank coffee. Then when I was 12 years old my younger brother and I went with my mother to visit her mother in Vienna and lived for six months in her coffeehouse, so I experienced coffee as a site of sociability. But I only started drinking coffee in college when the stuff coming out of our percolator was more a drug to help us study than a tasty beverage.

Steven Topik, a professor of history at the University of California, Irvine, is currently working on a world history of coffee.

In graduate school I decided to study the history of Brazil to understand its development. Since my area was political economy and Brazil has been the world’s leading exporter of coffee for over 150 years, it was a natural subject to study.

I also experienced coffee in its three most historically important geographic areas: the United States, Europe and Brazil. Since I became interested in issues of economic development and underdevelopment which led me to world history, coffee emerged as a wonderful vehicle to examine issues of exchange, development, colonialism, imperialism, the Cold War, national identity, public spaces, ecological issues and many more.

Without giving away too much of what you’ll discuss Monday evening, why is it that the story of America’s enthusiasm for coffee is “an unlikely romance” in your view?

I called it an “unlikely romance” because many coffee aficionados discuss coffee’s “romance” and tell stories of dancing goats, spies and military heroes to explain coffee’s global spread. Coffee’s global reach is often treated as something obvious that needs no explanation: people on every continent drink coffee because it tastes good. In fact, there were many barriers to coffee’s diffusion.

In the U.S. we have various stories about coffee’s ties to our national identity linking it to John Smith, colonial coffee houses, the Boston Tea Party, the westward movement and values like liberty, sovereignty, industriousness, battlefields and innovation. Some of that is historically true. Much of it, however, is more sales pitch than historically accurate portrayals.

The “romance” is unlikely also because coffee was not native to the U.S., it does not grow in the U.S., we had no important coffee colonies and most ex-British colonies favor tea over coffee. But I will explain that the U.S. becoming the world’s leading coffee importer does make sense in light of many other historical currents like trade in the Atlantic, immigration from Europe, anti-tax sentiment and coffee’s pharmacological effects.

What role has St. Louis played in the history of coffee?

While St. Louis is not as closely linked to the history of coffee in the U.S. as it is to the history of beer, or tea (British tea publicists claimed the first time iced tea was introduced was at the 1904 World’s Fair [though this is dubious]), it does have a significant role. Missouri was important in disseminating coffee in the U.S. because Independence, Mo., was the starting point of the Santa Fe Trail, and coffee for the Oregon Trail or the wagon trains to California set out from Missouri.

The coffee was imported from South America in New Orleans and then brought up the Mississippi River. By the 1860s-70s, St. Louis had seven coffee roasting companies, which made it a center of coffee roasting in the Midwest. The first commercial coffee roasting machine in the Midwest was worked by James H. Forbes in 1854. In 1911 the National Coffee Roasters’ Traffic and Pure Food Association was founded in St. Louis – a forerunner of first the National Coffee Roasters Association and then the Associated Coffee Industries of America. Coffee traders from St. Louis played significant roles in it. I’m afraid that’s as much as I know about the role of St. Louis in the coffee trade, though I’m hoping to learn more on my visit.

Looking at the history of commodities and the world economy, what lessons do you find for today?

The study of commodities and commodity chains are excellent means of understanding the Janus-headed relationship of coffee growing areas (and other agricultural ones) and coffee importing areas. It allows one to examine not just the economic dimensions of the spread of a global commodity and the international linkages it creates, but also the evolving and sometimes contradictory importance of natural endowment, religion, culture, technology, gender and racial relations to shaping history. It is a means of understanding why the export of commodities has historically created both development in importing countries and sometimes underdevelopment in exporting countries.