Rachel Winograd, an assistant professor of research at UMSL’s Missouri Institute from Mental Health, discusses the scope of the opioid crisis in Missouri during a two-day conference titled “Opioids and the Workplace” last week at the Millennium Student Center. (Photos by Steve Walentik)

The opioid crisis has touched every segment of society with drug overdose deaths currently the leading cause of death for Americans under age 50.

A lot of the policy discussion around the crisis has focused on what the health care community can do to help people struggling with addiction.

But a conference Thursday and Friday at the University of Missouri–St. Louis aimed to explore the role employers can have in combating the epidemic by helping erase the stigma around opioid use disorder and steering people toward treatment.

“Opioids and the Workplace” featured more than two dozen speakers and attracted an audience of more than 140 people – including members of organized labor, health care providers, researchers, academics and law enforcement personnel – to the Century Rooms of the Millennium Student Center.

“Much of the study that’s been going on, for good reason, has been going into chemistry and the brain and treatment plans,” said Douglas Swanson, the coordinator for labor studies program at UMSL, who organized the conference in his dual roles with the College of Arts and Sciences and University of Missouri Extension. “What wasn’t being looked at we didn’t think was the impact that it’s having in taking people out of the workforce or not providing people pathways back in.”

The conference attracted more than 140 people, including members of organized labor, health care providers, researchers, academics and law enforcement personnel.

Swanson said the idea to examine the opioid crisis through that lens grew out of a pair of studies, the results of which were released within months of each other beginning in the fall of 2017.

One from the Recovery Research Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital showed that 9.2 percent of people in recovery are jobless involuntarily. A second from the Missouri Hospital Association showed that Missouri was spending $1.4 million per hour when considering the costs of health care, lost work productivity, substance abuse treatment and more for the thousands of the state’s citizens battling addiction and 921 who died of an opioid-related overdose in 2016.

“If you are in a job that has random drug testing and you have a hot test, you lose your job, you lose your health insurance, so even if you are mentally ready to go into recovery, you have to pay out of pocket,” Swanson said. “The reality is if you’re using, you probably don’t have the money to pay out of pocket. So it falls to other organizations to try to provide a safety net. But there is not an economy of scale to catch the people like that.”

Before diving too deeply into the work-related issues created by opioid abuse, the conference’s first session served to define the crisis.

Rachel Winograd, an assistant professor of research at UMSL’s Missouri Institute of Mental Health, kicked things off with a presentation laying out some facts about what’s happening in Missouri.

“The reason that we’re having so many opioid conferences, for those of you in this network and hearing about it on the news and hearing about symposiums and events and work groups and roundtables and meetings … is because so many people are dying,” she said.

Winograd, who leads the Missouri Opioid State Targeted Response grant, talked about the drugs that people are addicted to, including prescription pain medication, heroin and most significantly fentanyl, a synthetic opioid she said is responsible for more than 90 percent of opioid-related deaths in this region.

“Because fentanyl is so potent and kills so quickly, I actually don’t really prefer the term opioid crisis or even overdose crisis,” Winograd said. “What we are dealing with nationally and in Missouri, and specifically here in St. Louis, is a poisoning crisis. If we start using that language, different approaches will follow. It puts us in a public health mindset and framework that is required to deal with this public health emergency.”

Joining Winograd on the first panel were Nicole Browning, a clinical director for the National Council on Alcoholism & Drug Abuse based in St. Louis; Fredric Shaffer, a professor of psychology at Truman State University; and Dr. Carrie Mintz, an instructor in psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. All discussed the chemistry connected to dependence that makes it so difficult to stop using.

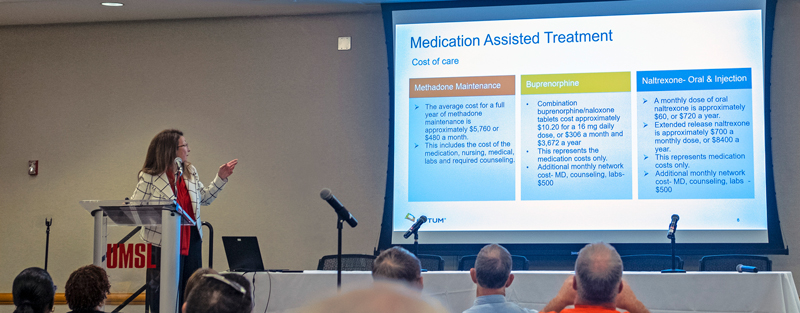

Debra Nussbaum, the senior director of behavioral health product at Optum, discusses medication-assisted treatment options her company covers.

Thursday’s second panel explored the economic impact of the crisis and featured a presentation by Debra Nussbaum, the senior director of behavioral health product at Optum, on the cost to employers for substance use disorder and specifically opioid use disorder.

Nussbaum also described a challenge health insurance providers face delivering treatment to the people who need it.

“We have a huge network of treatment providers, but how do we convince our membership that the programs that we’re reimbursing, that we’re paying for, that we’re cutting a check to, that are treating our members for substance use disorders are doing the best job possible and are providing evidence-based services?” Nussbaum said.

Additional panels on Thursday looked at promising alternatives to the status quo and other approaches to treatment.

Friday morning brought breakout sessions on opioid use, barriers to returning to work and challenges for immigrant communities.

Planned sessions Friday afternoon on opioids and the media and case studies on what to look for when family members or friends might be using were canceled because of inclement weather.

That was a disappointing conclusion, but Swanson still found plenty to be encouraged about over the two days.

“It’s the people who were in that room on Thursday and Friday that are going to be very instrumental in shaping what the next steps are,” Swanson said. “There were a lot of great ideas, a lot of innovative things being talked about.”

He expects to continue those discussions at future conferences.

Media Coverage

KSDK (Channel 5)