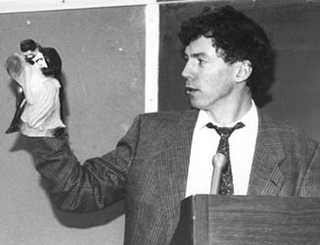

An expert scholar and highly effective teacher of medieval literature, the longtime UMSL professor and current chair of the Department of English is the recipient of the 2016 Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching. (Photo by August Jennewein)

Old English, Middle English, literary theory – the topics that dominate Frank Grady’s syllabi might not scream “fun” or “make sure to enroll quickly” to casual observers. But the University of Missouri–St. Louis students and alumni who have spent time in his classes know better. So do colleagues in the department that has been Grady’s academic home for the past 23 years.

“I was not surprised to discover that Professor Grady’s classes were the first to fill despite the fact that he taught some of the most challenging – and supposedly ‘boring’ – courses in the program,” remembers Founders Professor of English Richard Cook. “During the six years when I was chair of the department, I read through yearly student evaluations that consistently gave him the highest rating among his peers for effective teaching, for constructive feedback, for innovative teaching methods and for student mentoring.”

Semester after semester, Grady’s pedagogical approach to intimidating material ranging from “Beowulf” to “Canterbury Tales” to “Paradise Lost” has earned him a reputation for sparking student engagement at UMSL. And as of this fall, that classroom success has also earned him the 2016 Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching.

One of six faculty awards that will be presented at UMSL’s annual State of the University Address on Sept. 14, it includes a $1,000 honorarium in recognition of Grady’s dedicated efforts on behalf of his students. But when the longtime faculty member and current chair of the English department is asked to articulate what makes things tick so consistently well in his teaching, he’s quick to shift credit to the time-tested literature itself.

“If my classes are student-centered, it’s because the students are the ones who are encountering for the first time material that I have long found utterly fascinating, and their immediate experience of that encounter is inevitably the focus of my efforts as well as theirs,” Grady writes in his philosophy of teaching. “And if I have been successful, it’s because I’ve been lucky enough to be working with materials that will always be ‘pertinent.’”

Still, the questions arise: Are centuries-old texts really still relevant to 21st-century life? Why exactly does medieval English matter for contemporary students of the language?

In his answers to such skepticism, Grady aims for specificity.

Pictured here during a class “earlier in his career” at UMSL, circa 1995, Professor of English Frank Grady employs a teaching aid. (Photo courtesy of Frank Grady)

“When you close your book and put on your glasses to check the clock to see how much time is left in class, you’re drawing on three medieval inventions – the codex, eyeglasses, analog timepieces – while participating in the ongoing history of a medieval institution, the university,” he points out. “After class, when you swipe your ATM card to buy a latte while listening to a song on your iPhone about how much love hurts, you’re taking advantage of a system of credit and humming along to a version of romantic love that Chaucer and his generation would find quite familiar. So understanding the middle ages involves, in the first place, recognizing the ways in which they are still very much with us.”

Grady’s instructional finesse with topics that initially tend to seem so obscure offers another answer to such questions of pertinence – as does the feedback from UMSL students over the years. In his nomination of Grady for the teaching award, Cook cites student comment after student comment as evidence of Grady’s ability to make even the toughest material accessible and fun.

“The course is taught with impressive integrity,” writes one. “It is probably the toughest course I have taken in English, but Dr. Grady sold the material well enough to galvanize my continued interest.”

Another praises Grady as “extremely competent, engaging, intellectually challenging.” And still another, now a university instructor herself, notes, “I frequently resolve difficult academic and personal problems with my students and mentees by asking myself, ‘What would Frank Grady do?’”

For Grady, it all keeps coming back to the texts at the heart of his scholarship and teaching.

“I am always interested in how texts work – how they seek to achieve the effects that are attributed to them by readers, critics, writers, viewers,” he says. “My pedagogy seeks to generate a semester’s worth of detective work, drawing on whatever hermeneutics of suspicion will best reveal what it is that the charming, beautiful, sublime surface of a text is trying to convey.”

Cook notes that while he’s known for years that Grady is a great teacher and student mentor, reading through the many letters of support and years’ worth of fantastic student evaluations drove home just how excellent a colleague Grady continues to be.

“Until then, I did not realize just how good he is, how much he has contributed to our students’ learning experience at UMSL,” Cook says, “and how much credit he has brought to UMSL’s reputation as an outstanding research and teaching institution.”