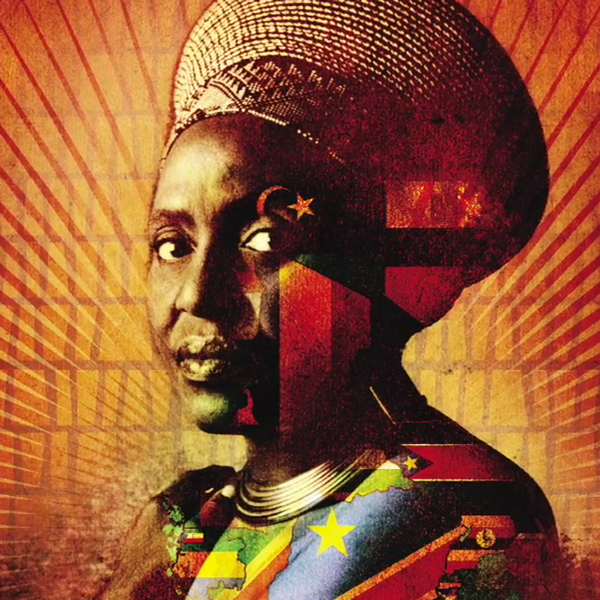

The cast of “Miriam Makeba: Mama Africa the Musical” surprised the UMSL campus community with a pop-up performance at the Millennium Student Center leading up to the production’s U.S. premiere at the Blanche M. Touhill Performing Arts Center Sept. 15. For tickets and more information about the show, click here. (Photos by August Jennewein)

She was a legendary musician and a civil rights activist, an exile and an ambassador. She was also someone who suffered immense loss.

“I’ve really come to appreciate the struggle more than I could have ever imagined,” says Niyi Coker, reflecting on the life and legacy of Miriam Makeba (1932-2008), a world-renowned artist who popularized African music internationally in the 1960s. For several years now, Makeba’s story has been a major focus for the University of Missouri–St. Louis faculty member.

“She took so many losses, personal and financial, doing what she did – standing up against apartheid and then being essentially driven out of the U.S.,” Coker says. “And then there’s the very hard life she lived in Guinea after that, trying to pick up the pieces, losing a child and losing two grandchildren, trying to rebound from that and keep her focus on the struggle.

“Through it all – understanding that ‘here’s my purpose, here’s my goal’ – I think those are very major accomplishments for any human being. And you just have to look at that and go, ‘Wow, she could have taken the easy way out at some point, but she never did.’”

Coker, the E. Desmond Lee Professor of African/African American Theatre and Cinema at UMSL, began exploring Makeba’s personal papers and talking to her family members as part of an ambitious project that has now come to fruition – and now to Coker’s home campus. His production “Miriam Makeba: Mama Africa the Musical” premiered in South Africa in May, and the U.S. premiere is set for Sept. 15 at the Blanche M. Touhill Performing Arts Center.

“This is a story of an icon that’s never been told,” Coker says of the musical, which is a collaboration of UMSL, the University of the Western Cape, ZM Makeba Trust and its wholly owned licensee Siyandisa Music, the home of Miriam Makeba’s intellectual property and archive. “It’s about people believing in a project. This is making history.”

In addition to her unprecedented work on the world stage as an African songstress, Makeba was a bold advocate against apartheid. Coker points out that her speech at the United Nations in 1963 resulted in the South African government revoking her citizenship and right of return.

“Nelson Mandela was in prison in ’63 – the only reason his name stayed on the consciousness of people is because of people like Miriam Makeba,” Coker says. “Mandela couldn’t do much in prison in terms of the outside world, because the apartheid government had shut all information about him down. But in terms of keeping his name alive and the struggle alive outside and in the consciousness of, say, the people in the United States or in Europe or in other parts of Africa and Asia, it was Miriam Makeba who was the big ambassador who would go around and in her performances would talk about it.”

South African actors treated lunchgoers in the Millennium Student Center on Sept. 12 with highlights from the new musical.

The new musical is, appropriately, a large endeavor. Forty South African actors arrived on campus last week for final preparations for the Sept. 15-18 run at the Touhill, which will be followed by another performance at the University of Missouri–Columbia on Sept. 28.

“Like me, they haven’t had any time to do anything else,” Coker says of his cast and crew. “They believe in this production very strongly.”

On top of the fact that the musical pays tribute to a pivotal musician and activist, it’s also significant in the history of South African performing arts more generally.

“Under the apartheid regime that ruled South Africa for many, many years, performing arts was not allowed in schools of color,” Coker explains. “If you belonged to a black school or ‘colored school,’ as they called it, you couldn’t have theater, you couldn’t have music, you couldn’t have dance. By the time apartheid ended in 1994 and the regime changed, those schools that didn’t have programs were not suddenly given resources. And those areas and institutions are still suffering, still lacking.

Monday’s pop-up performance on North Campus offered a small preview of the major new production “Miriam Makeba: Mama Africa the Musical,” written and directed by UMSL’s Niyi Coker.

“And so consequently there was a discussion with us, saying, ‘Let’s work on the performing arts. What is a production that we could do?’ And I said, ‘Well, I think I’ve got one – that’s relevant to South Africa, a South African story, and this is something we should pursue.’”

Coker describes the musical about Makeba as following “a trajectory of her discography,” with critical moments of her life paired with songs where she was writing and singing about those experiences. Learning more about various aspects of Makeba’s childhood from family members was particularly eye-opening to Coker as he developed his script.

“That changed the dynamic and flavor of the script immensely – it was one part of her life that I really knew nothing about, which was basically her spirituality,” Coker says. “Her mother was a Sango woman, which is a traditional healer. And so she had imbibed a lot of those teachings and trainings, and it carried through in her music, and I started listening for more of that.

“Something odd had happened in her life when she was 7 or 8 years old. A friend of hers had been struck by lightning right next to her. And I got to speak with the child that was born the day the lightning struck her friend.”

Coker met the child – Makeba’s niece – in Swaziland and heard the story from her.

“Makeba was witnessing both this friend’s death and her niece’s birth at the same time,” he says. “So I started to understand the symbolism, the importance of lightning, for her. Whenever there was lightning or thunder, it meant something in her life. And a lot of things happened that drew those parallels to that early nightmare she had.”

Miss the flash mob at the Millennium Student Center on Monday? Here’s an audiovisual sense of it, via the lens of campus photographer August Jennewein.

Media coverage:

St. Louis Public Radio | KWMU 90.7

The St. Louis American

KTVI (Channel 2)

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Riverfront Times

Columbia Missourian