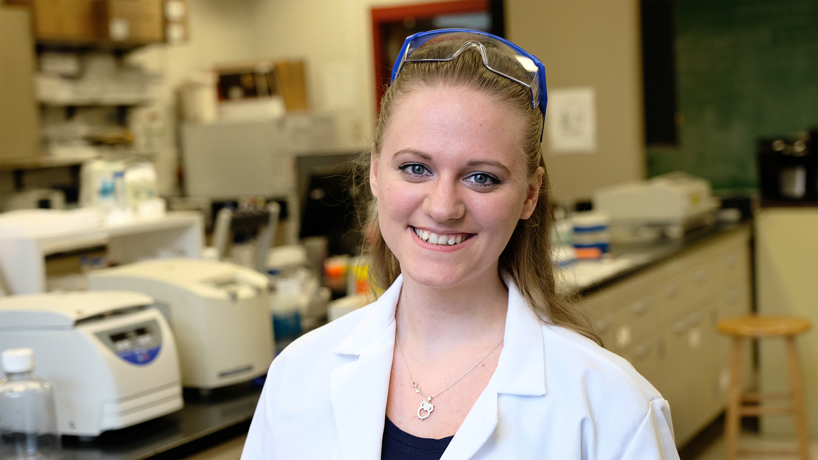

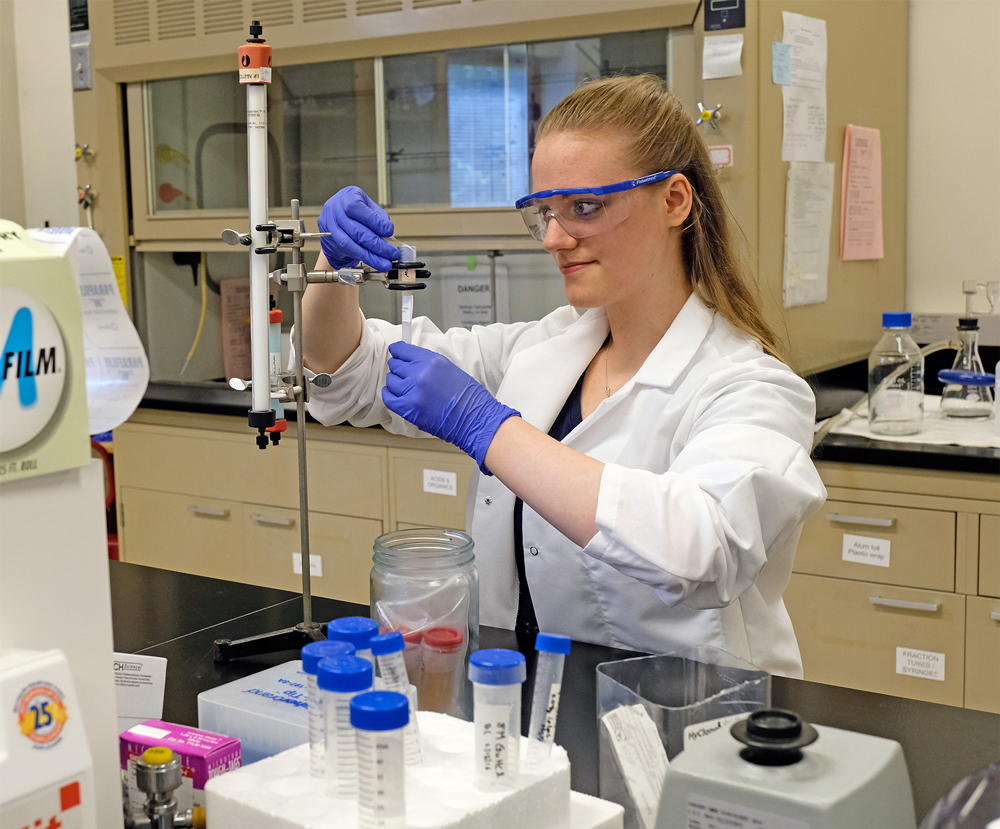

Victoria Rogers will pursue a PhD in biochemistry at Washington University in St. Louis after doing cutting-edge Alzheimer’s research in Associate Professor of Chemistry Michael Nichols’ lab at UMSL. She hopes to one day have her own research lab to devote to studying Alzheimer’s, which her family has suffered with personally. (Photos by August Jennewein)

Nothing stops Victoria Rogers – not time, not challenge and certainly not stereotypes.

The University of Missouri–St. Louis graduate has been on the go daily from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m., earning her biochemistry and biotechnology degree, working three jobs, being a powerhouse undergraduate researcher and proving her father wrong.

Rogers’ father raised her to believe women couldn’t do science.

His daughter, who was homeschooled and started college at 15, has now done cutting-edge research on the Alzheimer’s protein amyloid beta and been published in a scholarly journal as an undergraduate student. She had been considering communications or business but decided on science after taking chemistry and anatomy and physiology courses “just for fun.” A desire to know how things work and why they happen drove her to seek scientific explanation.

Victoria Rogers has helped the Nichols lab characterize and develop the antibody that will target the protofibrils responsible for the inflammation and cell death that causes Alzheimer’s Disease. The science research is something her father raised her to believe women don’t do.

Rogers, now 21, graduated from UMSL in December and accepted a spot in Washington University of St. Louis’ doctoral program for biochemistry. She’ll start there in June. In the meantime, she’s continued the research she credits with earning her spots in all five of the graduate biochemistry programs to which she applied.

Rogers has done four projects in six semesters in Associate Professor of Chemistry Michael Nichols’ lab, which focuses on the amyloid beta protein that triggers Alzheimer’s Disease.

Amyloid beta develops plaque on the brain – much like the plaque that develops on teeth. However, the protein does not start as plaque. It actually starts in a more soluble state that eventually begins to solidify and clump together to form plaque.

“You would think that the solid structure would be the cause of most of the inflammation that causes the degeneration of cells,” Rogers said, “but actually the worst part is what’s called protofibrils – those clumped together proteins that are still soluble but haven’t formed the plaque yet.”

Protofibrils are responsible for the majority of inflammation that causes Alzheimer’s. What Rogers discovered in an early project was that the immune cells of the brain actually take on the protofibrils more quickly than other conformations of amyloid beta in the brain.

“They basically eat anything bad to prevent it from causing harm to the brain, and they’ll eat these protofibrils more than anything else,” Rogers said.

The immune cells then send off signals saying, “Hey, this thing I ate is bad. Start an inflammatory reaction,” she said. Rogers and the rest of the Nichols team are developing and characterizing an antibody that targets the protofibrils.

“If we can target the protein with the antibody and hopefully sequester it or draw it out of the cerebral spinal fluid, it won’t be there anymore to cause inflammatory responses,” Rogers said. “If you don’t have those inflammatory responses, which really are the cause of the cell death, then you can slow the development of Alzheimer’s.”

There are no cures for Alzheimer’s Disease, but the antibody from Nichols’ lab would help as a diagnostic tool, allowing diagnosis before plaque forms. It also has the potential to slow the advancement of Alzheimer’s down in a much more noticeable and measurable way than any other drug currently available.

Theoretically, the antibody would be injected into the patient, Rogers said, although the Nichols lab isn’t responsible for the clinical trials, only the design of the antibody.

In August 2016, Rogers landed her first scholarly publication alongside doctoral student Lisa Gouwens in “Brain Research” for the work. Rogers is also a second author on a manuscript currently undergoing peer review. It’s rare for undergraduates to have such publishing success so early.

“A lot of the data in there I generated,” Rogers said. “Dr. Nichols is fairly unique for letting his undergrads do as much hands-on work as they do. My experience is that I get to plan a lot of the experiments myself, which is a lot of responsibility, but I think it’s really good. At that point if you screw up, it’s your fault. You learn from it. And most of the time you don’t screw up because you know there’s so much pressure for you to perform.”

But Rogers does more than perform. Not only did she graduate from UMSL with a 4.0 GPA, but she worked as a research assistant for Nichols, as a residential tutor on South Campus and with her grandmother at her grandfather’s insurance company.

“I don’t sleep,” Rogers joked, “and I live off caffeine. There’s not a lot of free time or time for extracurriculars, but it’s OK. Most of my friends are studying too.”

A Chancellor’s Scholarship, a Pierre Laclede Honors College scholarship and two smaller department scholarships partially funded Rogers’ education at UMSL in addition to her income.

It turns out that Rogers’ family also has a personal stake in her research. Rogers’ great-grandmother died of late-onset Alzheimer’s.

“It was rough watching her forget who she was and forget who I was,” Rogers said. “My grandma is very scared of getting it as well. I watch her do Sudoku puzzles, trying to ward it off. Obviously, there’s a strong likelihood that I will get it at some point because of the possibility of a genetic link that can be complicated by environmental factors.”

That’s part of the reason why Rogers wants her own Alzheimer’s-focused research lab in the future. But she also just has an appetite for research that seems out of the ordinary.

“I’m not that special,” Rogers said. “I’m just trying to work hard and do the best I can. I’m not aiming to make some dramatic discovery that will make me super famous. You don’t go into research aiming for fame or fortune. I just want to do my small part to make some steps forward in our body of knowledge.”