Alexei Demchenko, Curators’ Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry, will receive the Academy of Science–St. Louis’ Fellows Award at the 26th annual Outstanding St. Louis Scientists Awards dinner in April. Demchenko and colleague Keith Stine recently received a $1.3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to advance their efforts to create an automated process for carbohydrate synthesis. (Photo by August Jennewein)

One might expect Alexei Demchenko to be basking in all the recent attention and acknowledgement that has come his way over the past two months.

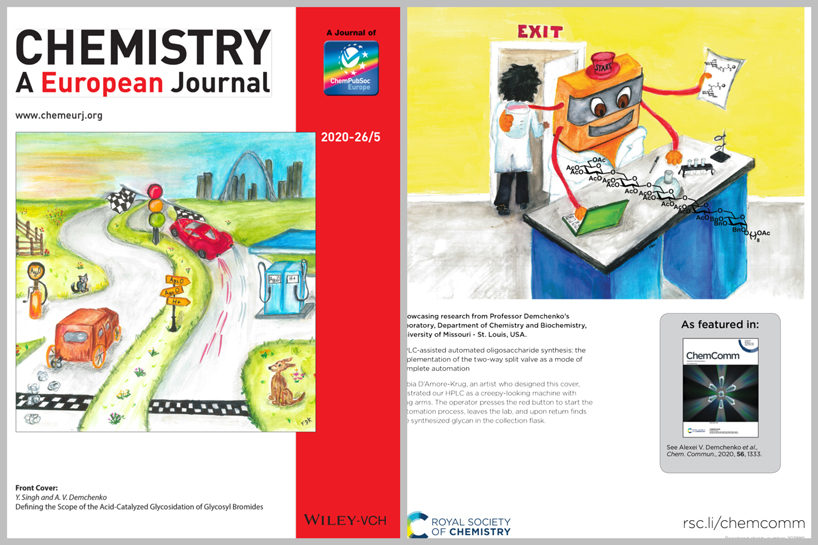

The Curators’ Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Missouri–St. Louis has seen one article he co-authored adorning the cover of Chemistry: A European Journal and another featured prominently in ChemComm. The National Institutes of Health awarded him and colleague Keith Stine a $1.3 million grant to advance their work in automation of the chemical synthesis of human milk oligosaccharides. Demchenko also learned the Academy of Science–St. Louis had chosen him to receive a Fellows Award at the 26th annual Outstanding St. Louis Scientists Awards dinner in April.

But no matter what an outsider might assume, Demchenko doesn’t feel like his work has been any more fruitful than what he’s expected of himself throughout his career.

But no matter what an outsider might assume, Demchenko doesn’t feel like his work has been any more fruitful than what he’s expected of himself throughout his career.

“I don’t feel like this year’s really unusual,” said Demchenko, downplaying the significance of the cover placement, which required an investment by his lab to commission the artwork and submit it for consideration – an invitation he typically declines.

“The award is definitely a big deal,” he added. “I don’t get awards every year. It was very unexpected, and I’m very happy about it. But with a lot of success, lots of responsibilities come as well.”

Demchenko, who earned a PhD in carbohydrate chemistry from the Zelinsky Institute of Organic Chemistry in his native Russia, and spent time at the University of Birmingham in England and at the University of Georgia before coming to UMSL, has long been a noted researcher and prolific publisher.

He has authored more than 180 peer-reviewed articles in leading journals such as Angewandte Chemie, Chemistry: A European Journal, Journal of the American Chemical Society, The Journal of Organic Chemistry and Organic Letters. NIH and the National Science Foundation are just two of the funders who have supported his work, and he had received more than $2.5 million in grant funding over the past four years even before his most recent award.

He works hard to maintain that record of achievement along with the continued respect and admiration of peers across the country – and beyond.

Colleagues in the field elected Demchenko chair of the American Chemical Society’s Division of Carbohydrate Chemistry, and he’s currently serving the first year of a two-year term. He also has been president of the U.S. Advisory Committee for the International Carbohydrate Symposia.

“He has a presence, both locally and internationally,” Stine said. “He’s working with companies like Pfizer, but he’s also involved in organizing and attending international meetings and conferences. The footprint of people that he knows and that count on his opinion about research directions and how to go about organizing a community of scientists is very, very broad. It’s remarkable how he is able to keep up with all of these people and all of these different organizations.”

Carbohydrate chemistry is an area of growing biological and medical significance, and Demchenko’s lab – known to his colleagues and students as Glycoworld – specializes in synthetic methods that can produce complex molecules in quantities adequate for biological studies needed to advance drug development.

It’s work that fits neatly with the goals of the University of Missouri System’s NextGen Precision Health Initiative.

Alexei Demchenko commissioned his friend and artist Fabia D’Amore-Krug to create art depicting the chemical processes at the center of his research. The work on the left adorned the cover of Chemistry: A European Journal symbolizes the new and faster approach, symbolized by the fast car, to the Koenigs and Knorr reaction developed by Demchenko and postdoctoral fellow Yashapal Singh. The work on the right illustrates the process of automated carbohydrate synthesis using high performance liquid chromatography, a represented by machine with the start button on its head. (Images from Chemistry: A European Journal and ChemComm)

“Defining the Scope of the Acid‐Catalyzed Glycosidation of Glycosyl Bromides,” the article he co-authored with postdoctoral fellow Yashapal Singh, highlights a new approach to the more than 100-year-old Koenigs and Knorr glycosylation reaction widely used for synthesizing carbohydrate molecules. Singh and Demchenko figured out a way to significantly speed up the time it takes to complete the reaction with the addition of catalytic triflic acid. Their method produces high yields and less waste, and it occurs with a color change that makes it easier to monitor the progress and completion of the reaction.

“This is just a basic methodology study, so we didn’t make any important molecules,” Demchenko said. “But in principle the same method can be used to build molecules that would be biologically or pharmaceutically relevant.”

In a separate work published in ChemComm, recent PhD graduate Matteo Panza, Demchenko and Stine describe the implementation of an automated process for chemical synthesis. This method can potentially be applied to the synthesis of human milk oligosaccharides.

Those are the sugars that occur naturally in human breast milk. They’re believed to play an important role in babies’ health by boosting immune systems and blocking pathogens. They also have probiotic effects, helping infants develop friendly bacteria in the digestive system, and many believe they provide important building blocks for the brain.

More than 200 oligosaccharides have been found in human breast milk, and the structures of 162 are currently known. Scientists are interested in gaining a better understanding of how each one works.

“If, for example, the scientists had this spectrum of 162 individual compounds and they realized that somewhere in the world kids are particularly healthy and they notice that mothers in that area produce huge amounts of a particular oligosaccharide, some scientist will be interested in testing that particular compound,” Demchenko said.

Researchers would need to be able to gain an easy access to the molecule to conduct those studies, and synthesis could help meet that objective.

NIH is investing in the automated process Demchenko and Stine have introduced to try to speed up the time it takes to synthesize the molecules. It relies on high performance liquid chromatography equipment to more efficiently mix the chemicals and run the reactions. The hope is that what today might take an experienced researcher as much as six months to do using traditional laboratory methods could be completed overnight at the push of a button.

“If you try to ask some company to invest six months of their time to make some complex molecule, even in small amounts, good luck,” Demchenko said. “It’s going to cost millions.”

The new grant will allow Demchenko and Stine to continue funding graduate research to refine the technology over the next four years. It could make a significant impact on carbohydrate chemistry in the years ahead.

“Carbohydrates is really a frontier area where there’s a lot that remains to be understood, and a lot of important work needs to be done that could impact health care and biotechnology and all kinds of different fields,” Stine said. “Alexei’s right at the center of a very important and very active and essential area of modern chemistry.”