Assistant Professor of Anthropology Anne Austin’s discovery of tattoos on a mummy at the site Deir el-Medina and unlocked new understandings about the role of body art on women in ancient Egypt. (Photo by August Jennewein)

Anne Austin was holding an iPad rigged with an infrared camera over a mummified torso. It was a long shot she didn’t expect to work. But the camera revealed what she was looking for, something the naked eye could not see: a swath of ancient tattoos.

“This unexpected discovery, you could feel it in your heart,” she recalls. “It leaps to see something that you know no one has seen for thousands of years, to find something that is otherwise invisible and then becomes visible.”

Austin, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, had found some of the earliest physical evidence of tattooing in ancient Egyptian society. Since then, her research has gone on to challenge previous understandings of the subject and garner interest from news outlets around the world.

That scene unfolded at Deir el-Medina in 2014, an Egyptian archaeological site Austin has been visiting since 2012 with the French Institute for Oriental Archeology.

“I normally focus on bones, studying human skeletal remains and using that to reconstruct things like health, disease and demography,” she says.

Anne Austin uses an iPad with an infrared camera to reveal previously unseen tattoos on a mummy discovered in Deir el-Medina. (Photo courtesy of Anne Austin)

Deir el-Medina especially interested Austin because the remains at the site had never been studied before. It was home to artisans who crafted royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings and was originally excavated in the 1920s to 1950s. However, studying human remains was not prioritized, leaving much of daily life at Deir el-Medina unexamined.

It turns out researchers could learn a lot. Austin was examining remains in 2014 when she made her initial discovery. An unmistakably bold tattoo on the throat of that first mummy caught her eye.

“I pulled back to look at the rest of her body,” Austin says. “Things that at first glance you would dismiss as maybe just irregular patterning from mummification – because there are all these resins they used that leave lines on the body – I looked more closely and realized they were tattoos.”

In total, she identified about 30 distinct tattoos on the mummy, many of which are known hieroglyphs and symbols. Unfortunately, her research expedition was nearly finished.

“I didn’t really fully study that mummy until 2015 and 2016,” Austin says. “Then I thought, ‘Well, I should reevaluate whether tattoos are present elsewhere.’”

Return trips in 2016 and 2019 confirmed her hunch when more infrared scans revealed tattoos on the remains of six more female bodies.

Austin presented her updated findings at the annual meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research in September 2019. An international media blitz ensued, and outlets such as Smithsonian Magazine and The Sun ran stories.

While Austin is happy for the attention, she’s more excited about the story the tattoos are starting to tell. Prevailing notions about tattooing in ancient Egypt were shaped by early scholarship written primarily by men. Tattooed female bodies were often eroticized as a result. Antiquity wasn’t much different. For a site with a rich textual record, it’s striking that there are no references to tattooing at Deir el-Medina.

“In ancient Egypt, the majority of people who are literate were men,” Austin says. “That means that we’re missing a lot of women, a lot of children.”

Tattoos say what the texts don’t. The first body Austin examined contained many depictions of animals, such as baboons, and floral imagery. More importantly, there were several symbols in very visible locations related to the goddess Hathor, a sky deity. To Austin, that public connection to the goddess indicates the mummy might have had an important religious role. It’s possible she was a priestess or healer.

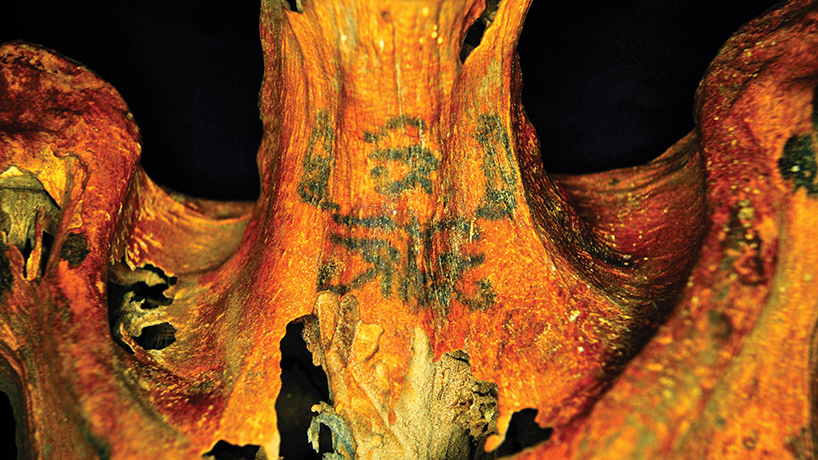

“We have tattoos on her body that make this phrase ‘to do good’ in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs,” Austin says. “They’re placed on her neck as well as her arms. I don’t think that’s a coincidence. I think it’s quite intentional. The ones on her neck cover her voice box, and so when she spoke or sang, those vibrations would have touched the tattoo and would have gotten the benefit of this ability to do good.”

This is related to an ancient Egyptian concept called “contagious magic.” According to this belief, her voice would have been imbued with special gifts by coming into contact with the hieroglyphs.

- The tattoo on the neck of this mummy means “to do good” in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and might have symbolically given its power to her voice when she sang or spoke. (Photo courtesy of Anne Austin)

In her more recent research, Austin found a tattoo associated with Bes, a god linked to the household, on one of the other mummies. Tattoos of the deity had previously been depicted in artwork, but this was the first physical evidence. Austin says there are other familiar symbols, too, but she’s not quite sure what they mean yet.

“Of all the recent tattoos that we found and of all the ones from the mummy that we first identified, we have no exact match across two individuals with the same symbol in the same location,” Austin says.

The lack of a pattern points to the practice potentially being more individualistic than researchers previously assumed. Austin is gradually starting to fill in the gaps to paint a more complete picture of life in ancient Egypt.

“Scholars dismissed tattoos as something that’s just about eroticizing female bodies,” Austin says. “That’s one way of explaining why they only show up on women’s bodies. But the evidence that we’re getting suggests that it’s probably more complicated than that.”

This story was originally published in the spring 2020 issue of UMSL Magazine. If you have a story idea for UMSL Magazine, email magazine@umsl.edu.