MIMH Associate Research Professor Rachel Winograd helped lead a dialogue about the racial disparities in overdose deaths in the St. Louis region. (Screenshot from Zoom conference on June 19)

Rachel Winograd has been helping guide Missouri’s efforts to combat the epidemic of drug addiction and death from opioids for more than three years as director Missouri Opioid State Targeted Response project.

In that time, the associate research professor at the Missouri Institute of Mental Health at the University of Missouri–St. Louis has seen disparities in the way addiction impacts people in different racial and ethnic groups.

Winograd joined with Dr. Kanika Turner from Family Care Health Centers to lead a regional dialogue on racial inequities in overdose deaths in St. Louis via Zoom Conference on June 19. More than 100 people tuned in to listen as they reviewed new data and discussed institutional racism and big picture efforts before opening up the 90-minute conference for questions and discussion.

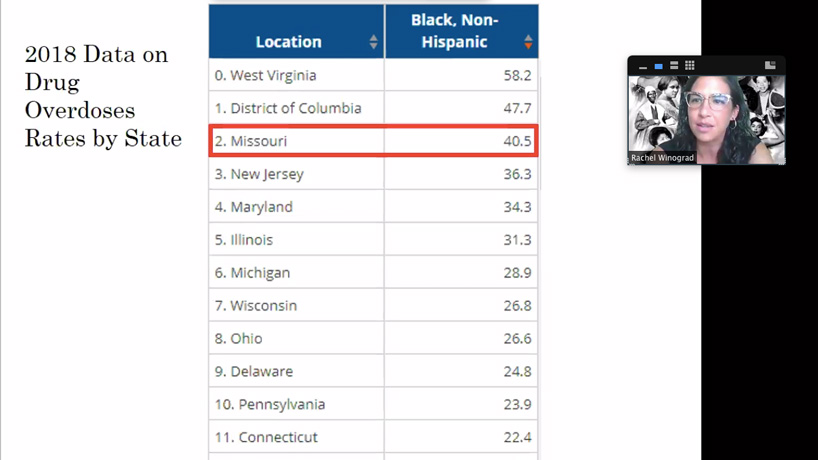

“We’re going to get started by jumping right in with some stark figures,” Winograd said as she opened the dialogue. “Notice on your screen you’ll see that Missouri is ranked third in the U.S. in terms of the death rate of drug overdose among black people. If you don’t count D.C. – because it’s technically not a state – we’re second. “This pattern has held true for a number of years, and you can see it illustrated in the map of the U.S. here that we’re in company with just a handful of other states in terms of how high our death rate is. As a state, we have a lot of work to do.”

Missouri’s rates are approached or exceeded only by states such as West Virginia, New Jersey, Maryland and Illinois, all with rates of more than 30 deaths per 100,000 people, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The majority of Missouri’s drug overdose deaths happen in the eastern part of the state, centered in the St. Louis area, and they’ve increasingly been driven by fentanyl in recent years.

The overdose death rates among black males in both the city of St. Louis and St. Louis County have been climbing since 2015 even as the region has seen declines by most other racial and gender groups.

“They were actually the only group to demonstrate an increase in deaths in St. Louis city and St. Louis County,” Winograd said.

Winograd also shared data specific to neighborhoods in the city of St. Louis. It revealed higher overdose rates in those with higher percentages of African American residents.

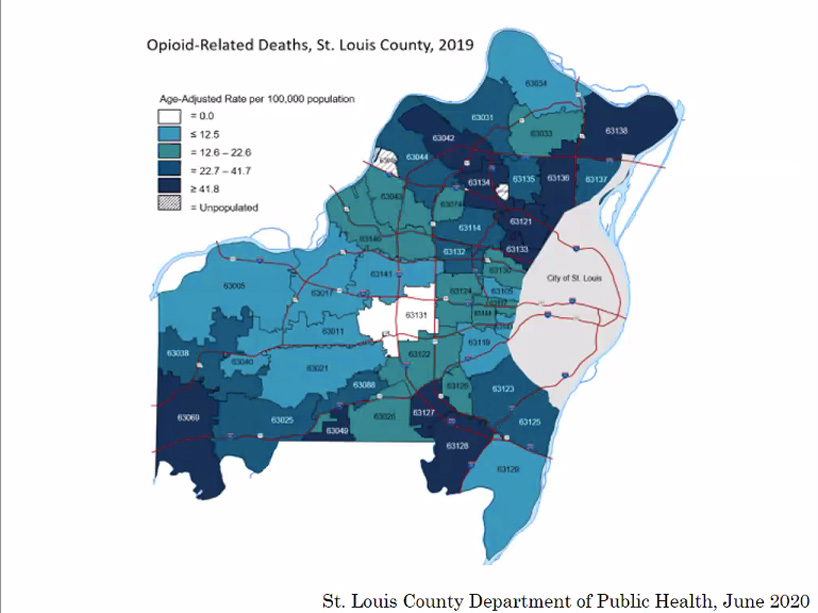

A map of overdose death rates in St. Louis County reveals higher rates in north county zip codes, which often lack resources compared to other parts of the St. Louis region.

A map of St. Louis County zip codes told a similar story.

“You see the darker shading represents higher rates, and those are predominantly in North County, which should come as no surprise for those of us familiar with the St. Louis region and the segregation in our area,” Winograd said. “North County has a lot of black residents and struggles in terms of access to care with a lack of addiction focused resources – safety net treatment programs, recovery housing and recovery community centers.”

Winograd noted that Missouri also ranks among the five states with the highest racial disparities in deaths from COVID-19 with African Americans dying at four times the rate of white people.

She turned the floor over to Turner, who discussed some of the historical and systemic issues around race that are underlying these issues. Turner talked about the disparities that resulted from such policies as the War on Drugs, first launched by Richard Nixon in the early 1970s, as well as the need to find ways to improve engagement and retention of African American clients in treatment.

When they opened the conference up for discussion, they heard from policy advocates and practitioners, including one UMSL student who works as a nurse at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, about the struggles they encounter daily trying to assist people with addiction.

Winograd and Turner plan to continue this dialogue in the fall with a goal of gaining broad commitment for specific policy changes that could help undo racial disparities and decrease the rate of overdose deaths overall.