Professor of Nursing Anne Fish and PhD student Fan Li interviewed 20 volunteer health care providers in Hubei Province of China for their study.

A pair of red high heels brought the initial stage of the pandemic into focus for Anne Fish.

In February 2020 – toward the start of the global health crisis – a nurse found those shoes under the bed of a patient who’d died from coronavirus.

“The patient had already been removed,” the University of Missouri–St. Louis professor of nursing said. “Yet they found these red high heels. This person had a background. They came with a story. They were dressed up, and they got COVID. They might have been rushed to the hospital, but they came as they were.”

Today, as the global count of coronavirus cases approaches 100 million, the COVID-19 pandemic has shattered normalcy, ending and upending lives worldwide. Though the vaccines have created a glimpse into a post-pandemic reality, in the beginning, uncertainty ruled.

From the outside, it’s near impossible to imagine the emotions and the experiences of those in the epicenter of the crisis at the start of the pandemic. But Fish and her collaborators – such as UMSL nursing PhD student Fan Li and Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine’s Qingqing Lou – have created a window to the historic moment through a qualitative study that documented the experiences of volunteer providers in the Hubei Province in China.

In December 2019, the first case of coronavirus was diagnosed in Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei Province. Though the province locked down quickly, the strain on the system was immense, especially on health care providers. By the end of February, more than 2,000 resident health care workers had contracted COVID-19, and more than 20,000 volunteer providers were rushing in to help.

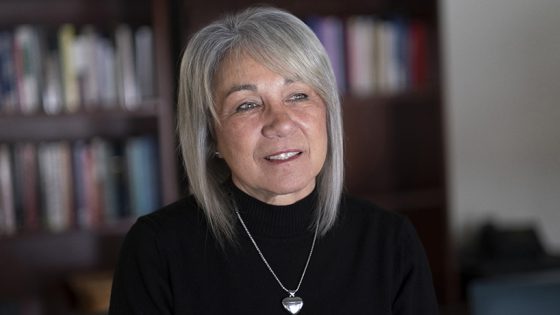

Donald L. Ross Endowed Chair for Advancing Nursing Practice Roxanne Vandermause provided her qualitative expertise in designing the questionnaire. (Photo by August Jennewein)

Fish and Li, with the guidance of qualitative expert Interim Dean of the College of Nursing Roxanne Vandermause and their China-based counterparts, designed a questionnaire that examined in-depth areas such as providers’ support systems, the hospital processes, national service, collaborations and motivations. That survey was administered to 20 doctors and nurses who had been part of that volunteer wave, and their answers were translated and then interpreted by Fish and Li.

From the results, they wrote a paper for which they are seeking publication.

“This is actual historical documentation,” Fish said. “We have a whole different perspective and an early perspective from right after the initial people were fighting. This team came in with the infection control period. When the interview starts, we still get this idea that there’s chaos, even if the larger medical centers have gotten a lot of things under control, the district or the smaller hospitals have less equipment and less expertise in infection control.”

Certain patterns emerged from the surveys, which they grouped into themes: national need and a call to serve, collaboration, a commitment to protect oneself properly to avoid infection, self-dependency, a recognition that challenges and opportunities were present side-by-side, family support in a national crisis and coping strategies.

“It’s quite amazing, the answers we got,” Li said.

Driven by the call to service, the cultural influence of communism and examples of parents’ service, providers often volunteered before telling family members their intentions. One nurse who was set to be married signed up before consulting with her fiancé. Another nurse’s father reassured her that he’d take care of her sister and mother since he couldn’t help as a health care professional.

“I had not told my mom before I left, but my dad knew,” one interviewee said. “They, he, was supportive. Actually, my family volunteered to go to Xinjiang in 1950s in response to the county’s call. My dad signed up like I did…Then, for my mom, I told her after arriving here. She was very happy. She said that I knew you would definitely go.”

Providers collaborated to quickly develop protocols to ensure safety. They established different “clean,” “semi-contaminated” and “contaminated” areas as well as methods for infection control. Li noted that doctors and nurses used social media, especially WeChat, widely to communicate updates.

Initially, there were personal protective equipment shortages, but volunteers focused on self-protection deliberately to keep themselves safe. Some hospitals initiated a video-monitored changing area where infection control staff could correct PPE slips in real time.

“[We were] sprayed with alcohol at the entrance [of the hospital],” one interviee said. “We took off our coats and left them outside the hotel… still needed to be sprayed in front of the room door… needed to disinfect and wash hands… We would prepare bleach in advance, just took off our clothes and threw them directly into the wash basin that had bleach… took a shower for half an hour. The hospital gave us eye drops. Then we disinfected the nose, eyes and mouth.”

Despite the circumstances, most volunteers were able to be self-reliant and didn’t feel that they needed external support. Providers often used social media such as WeChat as a coping mechanism and for communication as they were isolated from each other while not working, even during meals.

The volunteer experience bought some opportunities as well. There was a sense among them that this experience would prepare them for future crises, and some received gratitude, promotions or other compensation as a result.

For Li and Fish, who spent nine months analyzing the stories of the volunteers in depth, the experience was emotionally affecting.

“There was a feeling of an overall constant threat, and we could sense it all the time,” Fish said, describing a nurse who had shaved her head to prevent contamination.

The period of time in which the study took place was when the death toll was highest in Hubei.

“What really affected me is when people describe being in the suit; it was like I was in the suit with them,” Fish said. “It’s very moist in the suit. You have to concentrate on breathing because it’s a closed system. People had to do things like not drink a lot of water, or eat food, because they had no way of getting out of the suit for four hours.

“I pictured myself in the suit. I pictured worrying that there would be some crack or crevice, you know, around the glasses or where the glove would meet the gown and the thickness of the gloves. You really got a sense of their experiences living at that time.”

Li, who came to UMSL first as a visiting scholar while pursuing her master’s degree at NJUCM, played an invaluable role as the most bilingual individual working on the project and as a cultural interpreter and translator for the group.

For her, working on the research was more than an academic pursuit.

“I have a really strong commitment to this study,” she said. “Because I’m not a health care professional back in China, and I cannot fight with them on the front line, I really want to contribute, in my way. Sometimes, because I read the Chinese interview first, a lot of times I feel really overwhelmed and have tears in my eyes, and I want to say that. Yes, at first it was like no one is fully prepared. But they did what they can and did their best. The health care professionals really did their job in handling this crisis.”