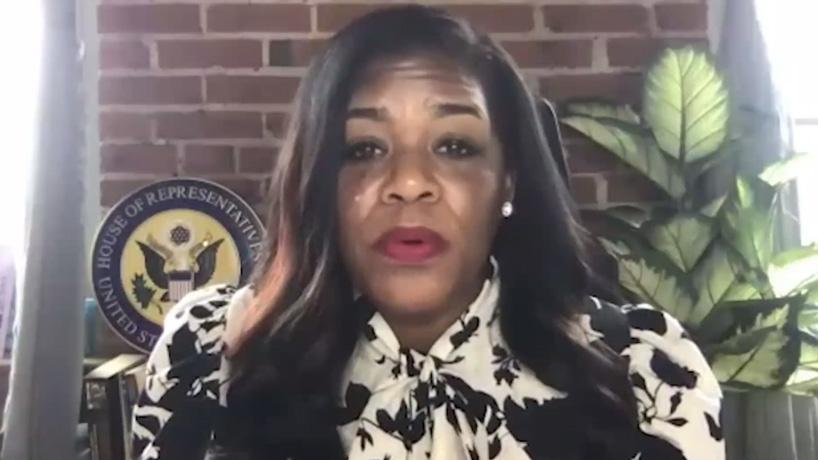

Congresswoman Cori Bush delivered the keynote address in a Missouri Climate Dialogues webinar titled “Green Recover, Climate Solutions and a Just Transition,” hosted by the University of Missouri–St. Louis and Washington University in St. Louis. The event, held last Wednesday, was part of a global project called Solve Climate by 2030, led by Bard College in New York. (Screenshots)

U.S. Representative Cori Bush understands the impact climate change can have on people’s lives, not just in coastal cities or far away islands, but right here in the Midwest.

The first-term congresswoman from St. Louis was once unhoused, living in her car with her children in the summer as the heat filled the inside of her vehicle on 90-degree days. Other times, Bush and her children did have housing, but she was often unable to afford to turn on the air conditioning.

“I can remember that feeling viscerally,” Bush told an audience of primarily college and high school students who tuned into last Wednesday’s keynote address in a Missouri Climate Dialogues webinar titled “Green Recovery, Climate Solutions and a Just Transition” and hosted by the University of Missouri–St. Louis and Washington University in St. Louis.

Because of climate change, Bush said the number of 90-degree days in St. Louis has increased by an average of 11 per year compared to when she was a child.

That’s put a strain on many people, particularly those living in low-income communities. Some of them are now Bush’s constituents.

Bush also told the her audience about living for a time in a townhouse near Coldwater Creek, a 19-mile tributary running through north St. Louis County contaminated by radioactive material. She remembers the creek flooding frequently near her son’s bedroom, potentially putting his health at risk.

She knows there are people today unable to relocate away from similar dangers.

“It is not a coincidence that I carry these experiences as a Black woman,” Bush said during the webinar. “It is not a coincidence that Black women are leading the fight for climate justice either. We are fighting for our very safety and survival.”

She argued for the United States to transition to 100 percent renewable energy by the end of this decade.

“The people of St. Louis, of Ferguson, of Normandy, of Florissant and communities all across Missouri’s first district cannot wait around for what establishment politicians think is reasonable,” Bush said. “Failing to act urgently is unreasonable.”

She wants to see more federal resources directed to frontline communities, many of them predominantly Black, Hispanic or Indigenous.

“My experiences at home in St. Louis have directly influenced by my legislative work in Congress,” Bush said. “They’ve led to my crucial partnership with Sen. Ed Markey in introducing the Environmental Justice Mapping Act in January. We must reinforce what we already know with data that can guide targeted federal spending to our communities, the ones that suffer the most from our climate crisis.”

Last week’s webinar was one of 125 similar events held worldwide as part of a global project called Solve Climate by 2030, led by Bard College in New York. The theme for the webinars was to Make Climate a Class.

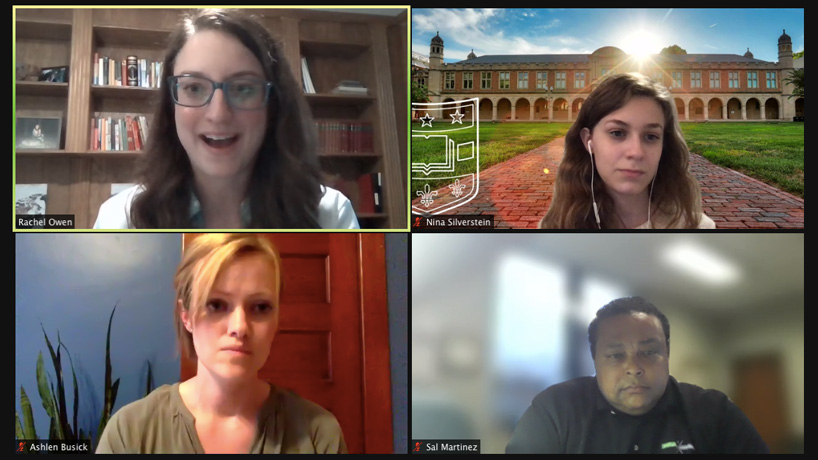

Washington University student Nina Silverstein (top right) served as the moderator for a panel discussion featuring Missouri Science and Technology Policy Initiative Executive Director Rachel K. Owen (top left), Socially Responsible Agriculture Project senior regional representative Ashlen Busick (bottom left) and Employment Connection CEO Sal Martinez (bottom right).

In addition to hearing from Bush, those who tuned in also learned concrete steps that can be taken to combat climate change from a panel featuring:

- Ashlen Busick, senior regional representative for the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project

- Sal Martinez, chief executive officer of Employment Connection

- Rachel K. Owen, executive director of Missouri Science and Technology Policy Initiative

Busick, who grew up on a family farm in northern Missouri next to one of the state’s largest corporate hog operations, now works to “empower people to protect their communities from the impacts of factory farms, or concentrated animal feeding operations, and to advocate for socially responsible futures.”

She talked about the benefits of shifting support away from large corporate farming operations to more small, diversified farms, which she said have the ability to adapt in times of crisis and also build healthier ecosystems by using more ecologically sound practices for improved soil health.

Busick spoke out against biogas, which captures methane from manure storage and uses it for fuel. She called it complex and expensive and said it incentivizes bigger animal numbers and therefore more manure production, increasing the potential for pollution.

Instead, Busick argued for more investment in renewable forms of energy.

Martinez discussed the benefits of training people to work in green jobs and ensuring those opportunities go to a diverse group of people.

His agency, Employment Connection, works to empower, employ and inspire its clients and help put them in a position to become self-sufficient. More than 90 percent of those clients identify as members of a minority group. About half are justice involved. They are often unemployed, underemployed and receiving public assistance, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits or living in subsidized housing.

Employment Connection clients are assigned a career specialist, who assists them with job training, job placement and other wraparound services.

“We had the pleasure of entering the green career arena a few months ago as we work with several partners to institute a pilot solar panel installation training program,” Martinez said. “As part of this initial pilot program, we devised a number of services that we would make available to the participants, including soft skills, preparing them for the workforce, exposing them to companies that are in the solar industry – in this case, StraightUp Solar and Azimuth Energy.”

Participants in the program received $15-per-hour paid internships and several were hired by private solar companies at wages starting at $16.50 per hour with benefits.

Owen pointed to the role governments can play in enacting climate-friendly policies.

She has a PhD in soil science and now works at the MOST Policy Initiative to connect science and policy across the state of Missouri by talking to lawmakers and answering their science-related questions about pending legislation. But she said there isn’t as much discussion as there needs to be at the state level about finding climate solutions.

Owen stressed the importance of establishing trust with people so that one can engage in candid conservations and start to develop real solutions.

“The things that I would encourage you to do today,” Owen said, “if you’re a scientist, if you’re a researcher, or climate advocate, is really take advantage of resources to think about climate communication.”