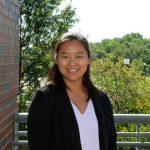

The American Optometric Association featured Assistant Clinical Professor of Optometry Erin Brooks on the cover of its magazine, AOA Focus, earlier this year. The story, titled “Optometry’s Reflection,” examined racial and ethnic diversity within the profession. (Photos by and courtesy of Paul Nordmann)

There are not enough hours in the day for Erin Brooks.

Whether she’s animating the physiology of a breathing lung in PowerPoint, creating a play about kidneys for her students to perform or relearning optics from the inside out to teach students in a different way, the assistant clinical professor of optometry at the University of Missouri–St. Louis often finds herself up into the wee hours of the morning almost seven days a week.

Her goal is to reach students in ways that will engage their attention, instruct conceptually and ultimately help them become superior optometrists.

“I want my students to be successful,” Brooks said. “I use all these different tools to help them see things. ‘Oh, they’re not understanding this. Let me see how else I can fix this. Like, what else can I do?’”

Brooks, who earned her BS in chemistry, OD and MS in vision science at UMSL, has taught in the College of Optometry since 2011. She’s devoted to her students’ success, offering intensive tutoring for those struggling in school or who don’t pass boards. She’s also passionate about the profession and known for her efforts in UMSL Eye Care’s Pupil Project, which addresses visual learning disabilities in children.

Earlier this year, Brooks became known to an even larger crowd when the American Optometric Association featured her on the cover of its magazine, AOA Focus. The story, titled “Optometry’s Reflection,” examined racial and ethnic diversity within the optometric profession.

Being on the cover of the profession’s largest member organization’s magazine is important, not only to Brooks, but to prospective students across the U.S. who can see that optometry is a viable profession for people of color.

Specifically, it asked why only 2 percent of practicing optometrists and 3.2 percent of students are Black when 13.4 percent of the U.S. population is Black and what could be done to increase the presence of underrepresented minorities.

“It’s important for patients to see people who look like them be their doctor,” Brooks said. “Just like some people want female doctors because they are female, and African Americans often want African American doctors because they feel that we’ll understand them better.

“If you look at the history of our country, and how sometimes minorities have been treated in health care, there’s a lack of trust. I think that trust is hard to build back. It’s easier to start with, you see me, and I look like you, and you’re more comfortable.”

Born to one white and one Black parent, Brooks initially couldn’t see herself as an optometrist but encouragement from her father, a liking for her family eye doctor and a visit to UMSL’s Pre-Optometry Club inspired her. As a doctor, she’s done significant work with students in Girls, Inc. – a junior high outreach program for minority girls – and in outreach at schools in Missouri and Illinois.

But even for Brooks, participating in the article and hearing about the experiences of one of her students awakened her to the importance of representation.

“I think I’m unique because I never grew up thinking I was a minority,” she said. “Maybe it’s not fair to say I didn’t think I was a minority. But I grew up thinking that that wasn’t fair to put me in that box.”

Going through high school and the UMSL Bridge Program, Brooks was one of the only mixed-race students and felt that her experience stood apart from both her Black and white peers.

“I’ve been told a lot of times I’m not Black enough,” she said. “It’s hurtful. I’ve also been asked a lot of times what I am, which is really fun. But I was not raised to see myself as a minority, and I think that was a good thing for me because I didn’t see the barriers that other people might see. I didn’t realize those barriers existed.”

Those barriers came home this year after learning that one of her students had decided to attend UMSL because of Brooks and Assistant Clinical Professor Angel Novel Simmons. The student had met the two during the admissions process and felt like she belonged.

Hearing that hit Brooks hard. She had bowed out of the admissions committee since due to her other obligations. She rejoined.

“I’m back on there because it’s important for our students who interview,” Brooks said. “She chose UMSL because she saw people like her. That changed things for me, and yes, the article definitely changed me.

“Optometry schools have very few minorities in them. It’s really hard for us to recruit, and it’s hard for them to feel like they belong when you have, you know, two people in the class or no people in the class who are minorities.”

That’s why being on the cover of the profession’s largest member organization’s magazine is important, not only to Brooks, but to prospective students across the U.S. The experience was also empowering for Brooks herself, especially doing the cover shoot. She spent several hours with the photographer, who worked hard to capture the significance of the subject.

“I felt there was this power kind of posing that that he was trying to accomplish,” Brooks said. “Not just you’re posing for this magazine, but you’re showing minorities in power, and that’s important for our patients, for our students, especially the girls because they get to see STEM careers, and I think that optometry is a very valid, viable career that doesn’t take quite as long as medical school to get through.”

Brooks has received positive feedback about the cover and the article from a wide group that spans her students and peers at UMSL to researchers and academics and administrators across the country.

Though she already devotes much of her time to outreach, the experience has left her wanting to increase her efforts. She’s planning on getting into more schools to share her passion for optometry.

“I love getting people excited about stuff,” Brooks said. “A lot of people go to optometry school because they have a family member who did it or someone who they know who did it. They’re not going to find optometry school, for the most part, on their own. I love helping people understand what optometry really is.”