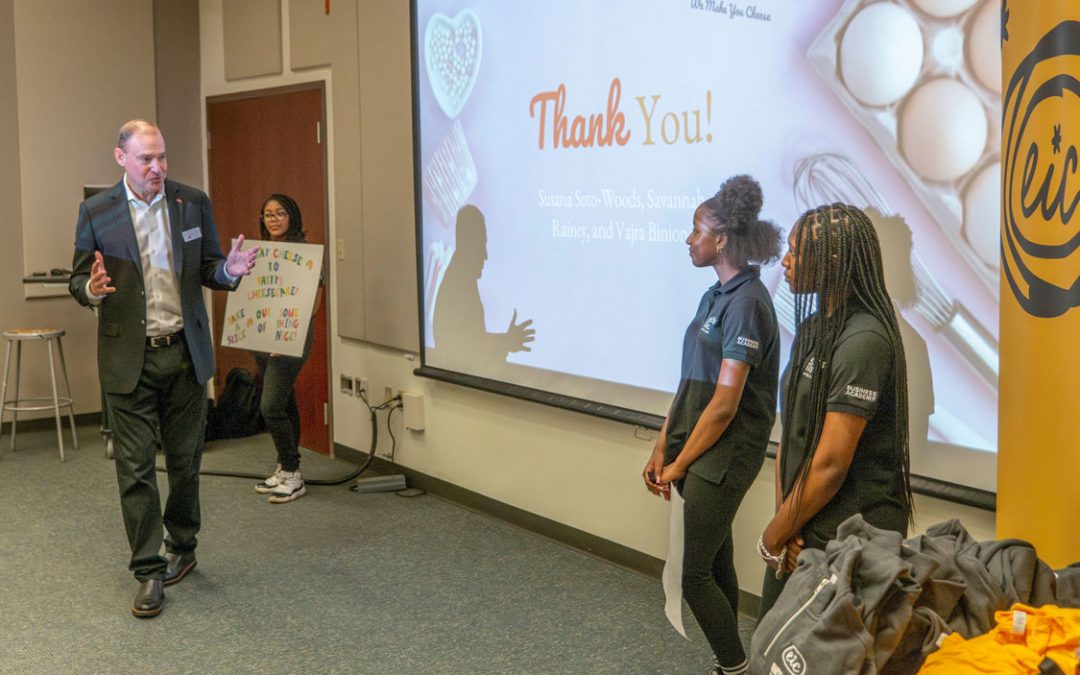

Felia Davenport, associate professor of communication and media, led a discussion on the history of Black people in horror films last week in the SGA Chamber at the Millennium Student Center. Over the course of an hour, Davenport touched on the history of tropes present in the genre and how they influenced socially conscious modern films such as “Get Out” and “Us.” (Photo by Burk Krohe)

As the audience filed into the SGA Chamber at the Millennium Student Center, Felia Davenport, associate professor of communication and media at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, asked the crowd a question.

“What happens when a Black person is in a horror film?” Davenport said.

With a laugh, much of the room responded, “We die!”

However, Davenport noted there was much more to explore regarding Black representation in horror and launched into her presentation, “Black People in Horror Films” last Tuesday. It was one of several planned events tied to national Black History Month.

Charles White, executive chair of the University Program Board, organized the hourlong event, which featured lively participation among the attendees. White said it was inspired by his love of horror movies and his desire to explore Black people’s relation to them.

“I thought that would be an interesting topic that no one really delves into,” he said. “It made me think about things that Jordan Peele has done like ‘Get Out’ and ‘Us,’ and I wanted to see the evolution. What was before ‘Get Out’? What was it like? I just wanted to see that.”

Sophomore Aliya Byers also had an existing interest in the topic and was excited to learn more at the event.

“I wanted to see what would be talked about and the different things we would analyze because I had recently learned more about this topic when I saw this documentary called ‘Horror Noir,’” Byers said. “It’s a documentary on Shudder that talks about Black people exclusively in the horror genre. It was really interesting seeing some of the different actors, directors, producers talk about these films.”

Junior Sabrina Kraus said that she’s not particularly a fan of the horror movies but wanted to be more aware of some of the genre’s tropes.

“There are certain tropes that you see, and I’m not as familiar with them,” she said. “I wanted to be well versed, so I could recognize them. Are they doing a service or disservice to people? How are they impacting how we understand things? I came here to explore that a little bit more.”

At the start of the presentation, Davenport explained that to understand Black people in horror films, you must understand the history of Black people in film more generally. She said the tropes present today harken back to earlier periods.

The first film she covered was “Birth of Nation,” a silent epic by D.W. Griffith about the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. Davenport noted that the film established many tropes that persisted beyond its creation, such as downtrodden Black women and the idea of Black men as aggressive and animalistic.

“This was used as a propaganda documentary to rebuild the Klan,” Davenport said. “In the process of this, Black people were depicted – especially Black men – as lusting after white women. So, that is how they were perceived. In film and early Black cinema and early cinema, that is what was shown to the world.”

Davenport noted that those tropes served as a through line to the cinema of the post-World War II “Atomic Age.” Black people were rarely depicted themselves, but movie monsters such the Creature From the Black Lagoon served as stand-ins.

Then she moved on to “Night of the Living Dead,” George A. Romero’s classic 1968 zombie film, where a Black man, Duane Jones’ character, Ben, serves as hero and protector. However, at the end of the film, he is shot by a white mob.

Davenport noted that Romero wrote the ending before casting Jones, and it underscored the importance of the viewer’s lens.

“That’s the thing, when you are creating any form of art, you can have whatever intention you want, but your viewer is going to see it through their lens and their experience and their life,” she said.

The next era Davenport examined was the 1970s and Blaxploitation films. While most were made on shoestring budgets and designed to profit from white and Black audiences, there were exceptions.

Davenport said that many films of the era depicted Black life negatively, but “Blacula” used the medium for social commentary. It also offered a more dignified, sophisticated depiction of Black characters via William Marshall’s Prince Mamuwalde and Blacula.

“When we watch films, we usually do it for entertainment value, and we don’t see the little nuances,” Davenport said after playing a clip from the film. “Right here, he is trying to negotiate to end the slave trade.”

Before moving into the modern era, Davenport touched on the early 1990s during the rise of young, talented Black filmmakers such as Spike Lee and John Singleton. Davenport noted that many Black horror films of the time, such as “Candyman,” “The People Under the Stairs” and “Tales From the Hood” were more socially conscious than other horror films at the time.

“This is your first horror film where – and it’s a supernatural horror film – it’s a Black man as the lead role,” she said of “Candyman.” “Yet again, this is the shift. We’re not the tokens anymore. We’re the leads.”

These films paved the way for the modern Black horror renaissance led by Jordan Peele, who directed hits such as “Get Out” and “Us.” Davenport highlighted “Get Out” specifically and said Peele used elements in the film such as the auction scene and the maid character to critique society.

“What is happening within Black filmmakers, and I’m very clear on saying Black filmmakers, because there are other filmmakers that are making horror that may not have that social commentary, but with Black filmmakers who are doing horror films now, they’re using it to talk about what is happening in this world,” Davenport said.

Byers and Kraus were both impressed with the discussion. Kraus said it was very enlightening and even more insightful than she was expecting. Byers concurred.

“I think it was an amazing presentation,” Byers said. “I really liked that people were able to come hear all the aspects and nuances that come with Black people being in the horror genre. Social commentary is key. People see horror as just blood and guts and gore, but sometimes it can be a lot more than that.”