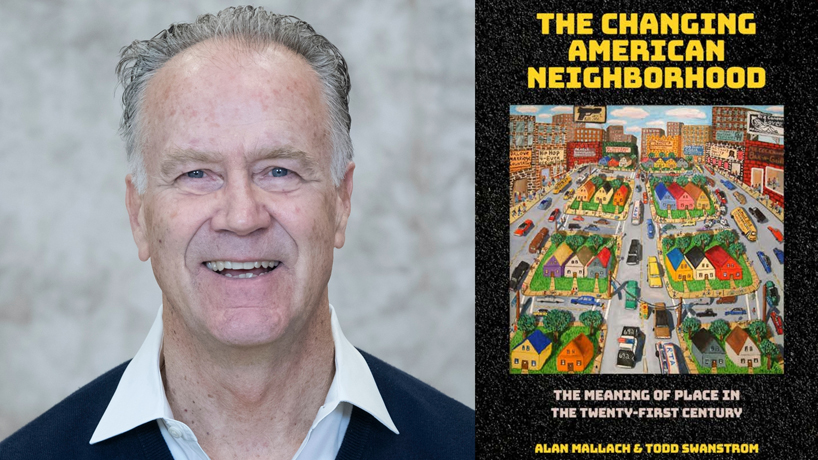

Todd Swanstrom, the E. Desmond Lee Endowed Professor in Community Collaboration and Public Policy Administration, has co-authored a new book titled “The Changing American Neighborhood: The Meaning of Place in the 21st Century.” (Photo by August Jennewein)

A romanticism still exists around the old, ethnic neighborhood, where children traveled in packs as they played in city streets and there was always a set of eyes looking out for their well-being.

Everyone knew everyone else, they conversed regularly with each other from their front stoops, and they often celebrated life’s big events together.

“Those kinds of thicker relationships in neighborhoods that we are kind of nostalgic about – that we sometimes want to go back to – are no longer common,” said Todd Swanstrom, the E. Desmond Lee Endowed Professor in Community Collaboration and Public Policy Administration in the Department of Political Science at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. “Air conditioning, handheld devices, the internet, and a bunch of other things have made that kind of neighborhood passé. It just doesn’t exist.”

There would also be issues if it did because those neighborhoods of the 1950s and 1960s were highly racialized and gendered, with women relegated almost exclusively to the role of homemaker.

The connections people feel today to the people who live next door or across the street might not compare to those experienced in earlier generations. But Swanstrom argues in a new book, “The Changing American Neighborhood: The Meaning of Place in the 21st Century,” that modern neighborhoods still provide important associations for the people who live there.

“The social ties in neighborhoods are what we call weak ties – that is to say they’re kind of transitory, they’re kind of superficial,” Swanstrom said. “You get to know people, but you’re not tight buddies with them. You don’t go to their baptisms and their bar mitzvahs. You don’t hang out on the porch with your neighbors, but you do get to know them. There develops a certain kind of tolerance and respect for people, and these modern weak neighborhood ties are actually very important because they provide connections across economic and religious and ethnic differences that divide Americans.”

Swanstrom co-authored the book with Alan Mallach, a senior fellow at the Center for Community Progress, a national nonprofit dedicated to comprehensively tackling vacant properties by providing guidance, free educational resources and leadership programming to assist policymakers, practitioners and community members working to return properties to productive use.

The two met at a meeting hosted by the center and connected over their extensive experience in community development, having each worked with local governments and community organizations to develop policies and strategies for strengthening cities and neighborhoods.

“We began to have discussions and decided that we felt the existing research in neighborhood change was not very valuable to those on the ground who are trying to do the work,” Swanstrom said. “We thought we could do better, so we decided to collaborate. We started out thinking about an edited book, and then our editor at Cornell University Press kept pressing us and saying that he thought we had something we wanted to say, so we ended up changing from an edited book to a co-authored book.”

They aim to balance the conversation in scholarly circles by discussing the issues of housing deterioration, disinvestment and decline alongside reinvestment and gentrification, which too often dominate policy debate.

Swanstrom believes there’s a tendency to view housing deterioration as a prelude to gentrification, but it can more often lead to housing vacancy and abandonment in many cities as Americans continue to move farther and farther from urban centers into more affluent outer suburbs.

“We’re in an age, we argue in the book, of simultaneous deurbanization and reurbanization with deurbanization – that is to say, outward movement and the draining of older urban neighborhoods – still the dominant trend,” Swanstrom said, “especially across the Midwest and the heartland like in cities such as St. Louis, Cleveland, and Detroit.”

The book is also critical of existing research, which often relies on quantitative studies isolating a single variable and uses that variable to predict neighborhood change. That includes attitudes about race, which might influence migration patterns, but race doesn’t act in isoloation.

Swanstrom and Mallach similarly push back against the idea that neighborhoods are sit helplessly at the mercy of global economic forces, which might lead to closing factories and the loss of jobs.

“The historical and geographical context of a neighborhood shapes its ability to change and to preserve itself and to revitalize itself,” Swanstrom said.

There are objective circumstances that impact a neighborhood’s ability to stabilize and revitalize itself, including the quality of the housing stock, its proximity to jobs, the quality of its schools and ease of transit. But people’s perceptions also play a critical role.

Swanstrom pointed to attitudes about race as one example. If the people in a neighborhood view racial diversity is an important characteristic of their neighborhood, he suggests it will remain racially diverse. But if people see racial integration as something that will lead to a tipping point where nearly all white residents flee, that will be its destiny.

The book is meant to serve practitioners working on the ground in community development and remind them that each situation comes with its own challenges and requires its own solutions.

“There’s no cookie-cutter approach,” Swanstrom said. “The community development movement in the United States is healthy in so far as it no longer does the slash-and-burn urban renewal process but rather tries to build on the fabric that already exists, and we think that’s how you build good neighborhoods.”