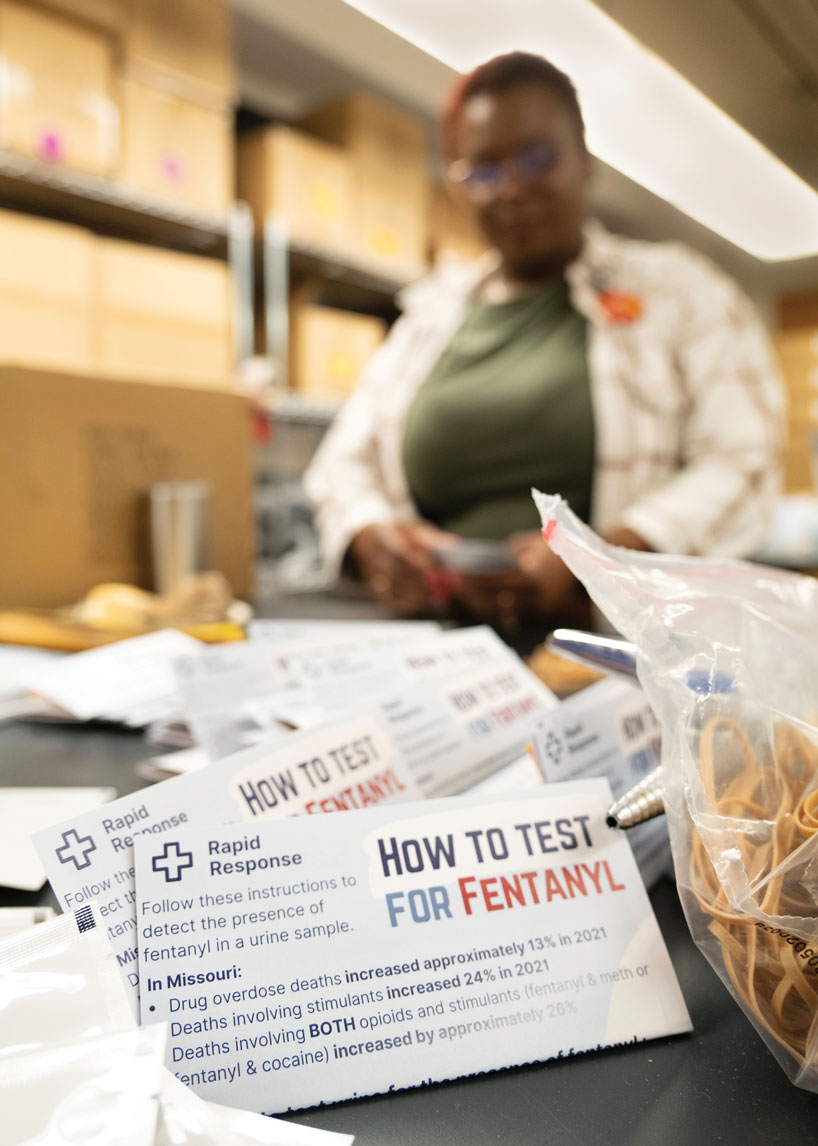

The University of Missouri–St. Louis Addiction Science team hosts weekly packing parties in order to supply the ongoing battle against the opioid crisis in Missouri and reduce overdose deaths. (Photo by Derik Holtmann)

Anyone walking through the first floor of Stadler Hall can probably hear the friendly debates – often about pop-culture topics like Beyoncé or Hollywood actors – spilling out into the hallway. But it takes stepping inside to realize the real purpose and seriousness of what’s going on when the University of Missouri–St. Louis Addiction Science Team gathers for one of its weekly packing parties.

Spread out on two sides of an old lab are stacks of pamphlets – one about the warning signs of opioid overdoses, another with myths and facts about medical-assisted treatments, still one more with ways to contact various treatment agencies.

There are also boxes of bag valve masks for assisting people with breathing when they’re experiencing an overdose event. They get pulled together with the pamphlets and stuffed into black drawstring backpacks, which are then packaged with doses of Narcan, the brand name for the overdose reversal medication naloxone. Another group at the back of the room is assembling small bags of fentanyl test strips with instructions for use.

These kits are an important tool as the team works to supply the ongoing battle against the opioid crisis in Missouri and reduce overdose deaths, which have been rising across the country over the past two decades. More than 109,000 occurred in 2022, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – roughly five times higher than the number of overdoses seen 20 years earlier.

“It can be really heavy,” says Elizabeth Connors, the team’s director of first responder and public health programming. “It’s nice that our team genuinely gets along. We have a lot of camaraderie.”

Members of the Addiction Science Team are on target to pack more than 200,000 kits this year. Eventually, they’ll get shipped to partner organizations across the state, including treatment providers, local public health departments, recovery community centers, shelter and recovery housing organizations, and a growing number of police departments, fire departments and EMS agencies working on the frontlines.

“The reality is that these save lives,” says Donald Otis, one of the team’s overdose prevention coordinators. “They do. Right now, packing them, I couldn’t tell you where this one actually will land. I have no idea. But we do know that it will go somewhere.”

***

UMSL has played a central role in Missouri’s response to the opioid epidemic since 2016. That’s when Rachel Winograd, now an associate professor with a dual appointment in UMSL’s Department of Psychological Sciences and the Missouri Institute of Mental Health, was named the principal investigator for the Missouri Opioid/Heroin Overdose Prevention and Education Project. A year later, the Missouri Department of Mental Health launched the Opioid State Targeted Response project after receiving a $20 million federal grant, and it installed Winograd as the project’s director.

Under Winograd’s leadership, the Addiction Science Team has been working to implement a harm reduction strategy over the past six years. It’s aimed at engaging directly with the people who use drugs and equipping them with tools and information to help stem the tide of overdose deaths.

It wasn’t always easy to find backing for that approach, but evidence has supported the philosophy behind harm reduction, and over time, it has become a key pillar of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Overdose Prevention Strategy.

There also have been more resources directed at combating the crisis, bolstered by settlements states reached in 2021 with prescription opioid manufacturer Johnson & Johnson and three major pharmaceutical distributors totaling $26 billion.

Unfortunately, the scope of the problem has also grown as synthetic opioids, most notably fentanyl, have flooded the drug market and proved much more potent than the heroin and prescription medication that once drove the epidemic.

Last year, more than 2,000 Missourians died from overdose – 1,579 connected to non-heroin opioid use – according to data from the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. That represented an increase in non-heroin opioid deaths of more than 135% since 2017.

“There are so many things outside of our control that contribute to these increases in overdose deaths,” says Winograd, pointing to the poisoned drug supply, the COVID-19 pandemic and other societal factors that have contributed to people’s use of drugs in the first place. “But then you just have to stay the course and be reminded what is within our scope – that we have an ethical responsibility to push for what we know can save and improve people’s lives.”

That includes the effort to deliver as much naloxone into the hands of people who need it as possible.

***

The state opioid settlements are expected to bring nearly half a billion dollars to Missouri over the next 18 years, and already, more than $6 million in new funding has found its way to UMSL. That money has allowed the Addiction Science Team to grow considerably, with 10 members coming on last fall.

One of them was Otis, who brought with him more than 30 years of experience working in treatment. Among their responsibilities, Otis and his fellow overdose prevention coordinators help implement the team’s naloxone and fentanyl test strip distribution strategy, working with organizations across the state to help spread overdose education and coordinate trainings for naloxone distribution. They also serve as community liaisons, working to foster collaboration and address community-level gaps and barriers facing people who use drugs.

The work feels as important as ever given the current nature of the epidemic.

“Drugs over decades, they tend to change,” Otis says. “Go back to the ’80s, you’re talking about crack. You go back to the ’70s, you’re talking about when cocaine came on board. Prior to that, it was opiates. It goes in a cycle, but this cycle here is a little bit different. I had seen episodes with what we would call bad drugs, but it was never fentanyl contamination like what you see right now.”

While Otis and others engage with community health centers and other community-based organizations and equip them with tools to educate and provide treatment to users, Addiction Science Team members Greg Boal and Joshua Wilson direct their efforts toward engaging with first responders.

Boal, a former Army medic, and Wilson, a former volunteer EMT, work with law enforcement, fire department and EMS agencies around the state to set up trainings and distribute naloxone for officers to carry with them on patrol. Together, they’ve assembled a team of consultants, including a flight medic and nurse in Pulaski County and assistant fire chiefs in Springfield, to deliver trainings on working with people with substance use disorder and deploying naloxone for cases of overdose to departments and agencies across Missouri.

“What we figured out is that first responders listen best and respond best to other first responders, so we have a lot of consultants around the state,” Wilson says. “There are two people involved with all the trainings. One of them is somebody who has experience as a first responder, either active or retired. Then we also have somebody with lived experience with addiction who partners with them to help put a face to the stories behind all this.”

***

When Wilson and Boal first came on board last fall, they were spending much of their time sending out cold emails to potential partners to let them know they had naloxone available. But with more and more news reports about Narcan popping up around the state over the past several months, or simply spreading by word of mouth among first responders, there’s increasing awareness of the role the Addiction Science Team is playing to equip officers and other first responders.

As a result, Boal and Wilson have found themselves fielding a lot more inquiries about how different agencies might schedule trainings and get supplies.

“We’ll supply somebody in Jackson County, and because first responders are very connected – they do a lot of interdepartmental work together – and they might say, ‘Where did you guys get your Narcan from?’ ‘Oh, we got it from the Addiction Science Team at UMSL,’” Wilson says. “Now there’s less outreach and just a lot of people are coming to us.”

Otis has seen the same shift.

“If not daily, multiple times a week, somebody in this crew, this team, is going to hear from a new person, a new entity, a new community,” he says.

The Addiction Science Team is eager to accommodate as many requests as possible while also sharing information about treatment and recovery services.

“Our goal really is to reach naloxone saturation in the state of Missouri,” Connors says. “As partners across the state have heard there is naloxone available, we’re starting to get requests for things that we didn’t anticipate, so we’re constantly getting the opportunity to be creative and pivot and ask, ‘How do we most effectively meet the needs of all of these folks?’”

One change they’ve made recently is to try to shift from supplying Narcan nasal spray to an intramuscular form of the medication because it is just as successful at reversing the effects of overdose and is much more cost-effective.

They’ve also begun piloting a program to have EMS trained and equipped to begin administering buprenorphine, a medication used to treat acute and chronic pain as well as opioid dependence.

***

The Addiction Science Team typically packs out about 3,000 kits per week – more if they receive special requests. They get boxed up with doses of naloxone in the room next door, which is filled with stacks of cardboard and large rolls of bubble wrap.

Winograd has found interest among her students in helping with packing.

Lily Franzen, a senior psychology major and member of the women’s swimming team from St. Paul, Minnesota, jumped at the chance to pitch in during the first week of the fall semester.

“I am planning on going to grad school, but I just don’t know for what yet,” Franzen says. “I have a couple things that I’m interested in, one being clinical social work with substance use disorder treatment. I thought this would be a good way to kind of see what this world is like.”

From inside Stadler Hall, it’s hard for team members to see the impact they’re having.

“What they do next door every week literally is life and death for people, but we don’t often get to see that side of it,” Connors says. “We just send things out and hope that it makes a difference.”

But there are signs things might be changing for the better. One was a St. Louis Post-Dispatch report in August that St. Louis County recorded a decrease of almost 11% in drug-related deaths last year. It marked the biggest year-over-year decrease in almost a decade and was the first decrease in drug-related deaths since 2015 when it dropped almost 8%, according to data provided by the St. Louis County Medical Examiner’s Office.

Members of the team take as much heart from news like that as they do from the reports that, through partners, find their way back from the field.

“We get feedback from folks like, ‘Hey, you sent us a leave-behind-kit, and I used it for my kid and they survived,’” Connors says. “Those are the things that we’ll share back with our team as a win because it can be difficult, emotional work. There are real lives on the other side of what we’re doing, and we are trying to keep people alive.”

This story was originally published in the fall 2023 issue of UMSL Magazine. If you have a story idea for UMSL Magazine, email magazine@umsl.edu.