Less than a month after an incredible natural phenomenon captured everyone’s attention – the solar eclipse on April 8 – another spectacle of nature is about to dominate headlines and fascinate Missourians. The cicadas are ready to emerge.

Billions of periodical cicadas (yes, with a ‘B’) have spent the past decade plus tucked away safely underground, and they’re about to rise and shine. You won’t be able to miss them, visibly or audibly.

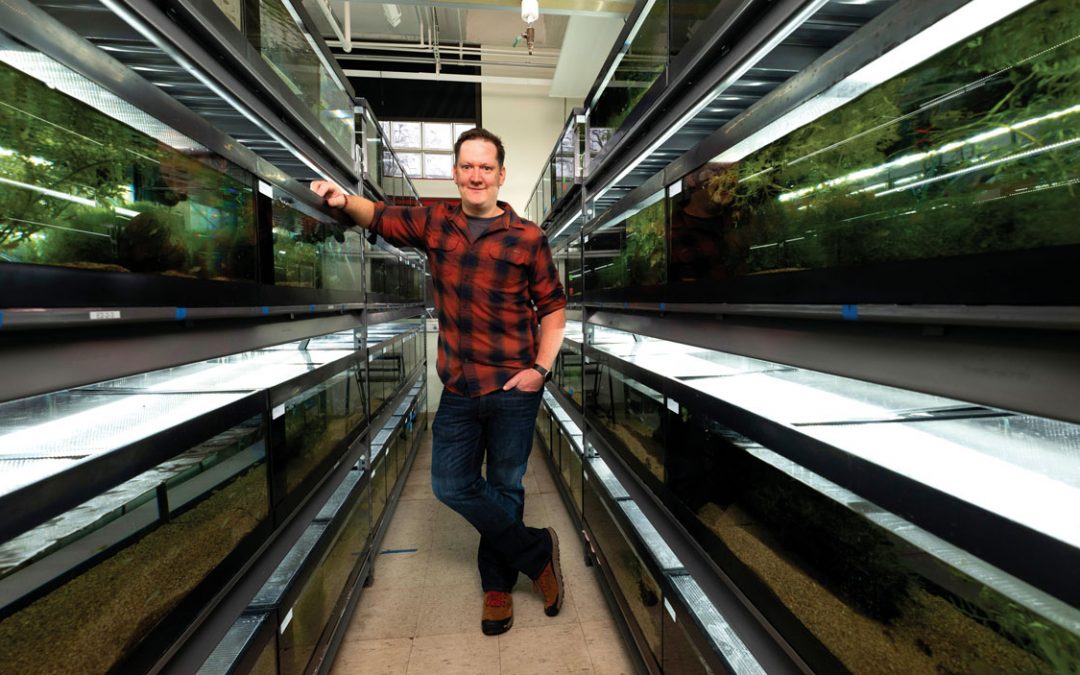

University of Missouri–St. Louis Department of Biology entomologists Sara Miller and Aimee Dunlap were kind enough to join UMSL Daily for a conversation about what we all might see over the next month. Neither Miller nor Dunlap specialize in cicadas, but both are excited for this rare event. Miller’s primary area of study is the diversification of wasps, and Dunlap focuses on the foraging habits of insects, especially bees and flies.

It just so happens this is a historic cicada emergence, with two massive broods set to compete for attention at the same time. Brood 19 is on a 13-year cycle, meaning they’ve spent the past 13 years underground. Brood 13 is on a 17-year cycle. The last time these two broods emerged at the same time, in 1803, Thomas Jefferson was president. This will not happen again until 2245.

The broods won’t overlap much, though, mostly just in an area in central Illinois, around Springfield. Brood 19 will dominate Missouri, southern Illinois and Arkansas, along with other states throughout the South. Brood 13 is mostly in northern Illinois, Iowa and Wisconsin. Generally speaking, the concentrations of cicadas will be higher in rural areas than in cities. In some areas, the concentrations of cicadas will be mind-boggling – as many as 1.5 million per acre.

Even in areas with fewer cicadas, the insects will make their presence known. The males “sing” to attract mates, using a special organ called a tymbal, and when there are hundreds signing at the same time, the noise can be rather intense. A cicada’s above-ground lifecycle is short; they’ll emerge, mate, lay eggs and then generally die within three weeks or so.

Dunlap and Miller met with UMSL Daily at the Harris Center in Benton Hall. Miller brought the department’s teaching collection of cicadas, gathered from past emergences (annual cicadas are larger than periodical cicadas) by Robert Marquis, an emeritus professor in biology at UMSL, with help from students in his Entomology class. In the fall, Miller will start teaching the same Entomology class that Marquis used to lead, the first time it’s been offered since 2018.

For the conversation, Miller wore a cicada T-shirt she bought from the Smithsonian to commemorate the event, and Dunlap wore cicada earrings. Inspired by the discussion, the dynamic duo decided to conduct an experiment measuring cicada calls in St. Louis. Andrew Hurley, an UMSL professor of history, will be assisting, and they’re looking for help from the UMSL community. If you’re interested in participating, shoot them an email (Dunlap/Miller).

Now, on to the cicada talk. (The conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.)

University of Missouri–St. Louis entomologists Sara Miller (left) and Aimee Dunlap. (Photo by Ryan Fagan)

UMSL DAILY (UD): What are you most looking forward to with this cicada event?

DUNLAP: It’s one of those things where I think everybody, especially entomologists, remembers one of these emergences from when they were a kid. I think that leaves an imprint – of horror for some people, but total curiosity. I don’t think I’ll see very many in my neighborhood, because it’s been developed since the 1800s, and anything in the soil has been disrupted in the years since. I’m planning to drive out. I want to hear all of the calls, the cicadas screaming, and hopefully see how many different species we can spot.

UD: Are there are different species of cicadas within the same brood?

MILLER: There are supposed to be three within St. Louis. I’ve been looking at distribution maps, though, and it’s hard to know exactly where each will be. It’s definitely a complex network. There are different year cycles, there are different brood cycles and there are different species within those combinations of broods.

DUNLAP: And to think they’re all just under the ground all the time, all those years, all the cycles and brood species.

MILLER: I think that’s one of the things we’re most excited about, being able to get an insight into the natural phenomena of all the cool biodiversity that’s in the world all around you but is normally hidden from view.

UD: What about here at UMSL? Do we have any idea of what to expect on campus?

MILLER: Most of the samples we have are from Tyson (Research Park) or out in Kirkwood and away from here. As Aimee was saying, if you have heavy machinery in your neighborhood, that squishes them underground.

DUNLAP: It could be that when this campus was constructed as a golf course – of course, UMSL is on a former golf course – that could have wiped out the cicadas. Once they’re wiped out in a place, they’re not coming back. They’re vulnerable in the 13 or 17 years they’re under the ground. If at any point in that process, if somebody dug a basement or graded the land, they’re gone.

MILLER: Probably in the more naturalistic areas around and outside campus, I would expect to see them. On campus itself, it might be more hit-or-miss.

UD: Do you two have a cicada story you remember?

MILLER: Most of my cicada stories as a kid involving seeing the casings and being chased around the lake, like, ‘what is this terrifying thing?’

DUNLAP: For me, it’s seeing them all stuck to the trees. When I was in the first grade, I didn’t live in Missouri, but I remember seeing those everywhere. It was just so cool.

UD: I remember very specifically being out at Busch Wildlife in St. Charles County when I was a kid, and they were everywhere. You literally couldn’t walk without squishing them.

DUNLAP: I would love that! I’ve seen pictures where they’re all over someone’s screen door. I remember when I was a kid, we were going over a bridge and the bridge was just covered in butterflies. They were migrating, just butterflies everywhere. Of course, we don’t see that amount of monarchs anymore. But it brings me back to something Sarah was saying earlier, about these really cool natural history things that are just spectacular, these migrations or emergences.

UD: Do you have plans to see them?

DUNLAP: I’m going to drive to Springfield.

UD: You’re going to the epicenter!

DUNLAP: Yes! I don’t expect these broods to sound different. Like, nothing I’ve read has said they’ll sound different, but it would be really fun to go right where they’re touching up against each other and be able to say I heard both broods.

MILLER: I’m going to get out to the arboretum or Tyson, something like that.

DUNLAP: Castlewood State Park, I bet that’s going to be a great place.

UD: I was reading that the cicadas are just waiting for the weather to warm up to emerge.

MILLER: The soil temperature has to hit a certain level and they’ll start crawling up.

DUNLAP: They’re usually like 8 to 10 inches underground, so it takes a little bit longer for soil temperature at that level to warm up. That’s where they live, munching on the roots of plants and tree roots.

UD: It should be starting soon, right?

DUNLAP: It should be any day now. There are soil temperature differences across the city and the area, so I’m sure there will be places where they’ll be emerging more quickly than others. They have already emerged further south.

MILLER: I saw they were already in North Carolina.

UD: Are there other types of natural phenomena that are at all similar?

MILLER: One of the hypotheses about why they all emerge at the same time is predator avoidance. This isn’t an insect example, but the wildebeests in eastern Africa, they all give birth within like two or three weeks of each other. They basically flood the system with all these baby wildebeests so there are enough of them, as many as half a million, that the likelihood of any one of them getting picked off by a lion goes down.

DUNLAP: And this is what monarchs do in their overwintering habitat in Mexico. There’s just so many of them. It’s called a dilution effect, because you’re diluting your individual risk of being eaten because there are so many of them.

UD: And these cicadas don’t sting or bite or anything, right?

DUNLAP: No, they don’t bite.

MILLER: They’re true bugs.

UD: What does that mean?

MILLER: We use ‘bugs’ colloquially to mean any insect, but from a taxonomic perspective, true bugs are hemipterans and they’re called that because they have piercing, sucking mouth parts. So, while they seem big and scary to us, they’re really only scary to trees and leaves and things like that. They have almost straw-like mouth parts they shove in and suck up the tree juices. They look kind of creepy if you’re not into insects.

DUNLAP: I think they’re beautiful!

MILLER: I mean, I think they are, too.

DUNLAP: Just the color mix is so beautiful, with the gold and the way it reflects the light. It’s so lovely. And the periodical cicadas with the red eyes and the black bodies? They’re very striking insects.

UD: So their calls, they’re doing that to attract mates, right? And it’s just the males?

MILLER: Just the males, right.

DUNLAP: Of course, they’re super loud. Anybody who’s heard them knows. But some of the cicadas in Asia can get way up on the decibel level, louder than even this (gestures to the lawn mower outside). That’s amazing to me, that something that small can create such a noise.

MILLER: Aimee kind of alluded to this, but the different species sing slightly different songs from each other, so that’s how they tell each other apart.

UD: Very cool. So, what are they doing for the 13 or 17 years they’re underground?

DUNLAP: They’re slowly growing and slowly feeding.

UD: Speaking of feeding, my dog has eaten a couple of the annual ones the past few years. I read they’re pretty nutritious and that’s why pretty much every animal eats them.

DUNLAP: Some people eat the newly emerged ones, too. Supposedly, when they first emerge as adults, before the exoskeleton hardens, they kind of taste like shrimp. I’ve read that any way you cook shrimp, you can cook young cicadas. I’m not sure if I’m going to try that or not.

UD: How long after they crawl out of the ground does it take for the exoskeleton to harden?

DUNLAP: It’ll probably be a matter of hours, a short amount of time if you’re going to do your cicada scampi, or whatever you’re interested in cooking. I would squeeze that in quickly. There’s nothing worse than eating exoskeleton.

UD: You said earlier they’re related to shrimp?

MILLER: They’re distant relatives. They’re all arthropods.

UD: I’m allergic to shrimp so I probably should not eat a cicada.

MILLER: Yeah, if you can’t eat shrimp, don’t eat cicadas. That’s generally a good rule. If you have a reaction to shellfish, they suggest you don’t eat insects or cricket flour or anything.

UD: That’s good to know. This Brood 19, the one that’s emerging in Missouri, how big is this one, relatively speaking? And how many periodical broods are out there, on different 13- and 17-year schedules?

DUNLAP: There’s generally always someplace to go if you want to go see cicadas. Maybe not every year, but it’s not like waiting for Halley’s Comet to come back. We’re not waiting 200 years. There’s generally a brood somewhere. Sometimes it’s a small brood. But this Missouri brood this year? It’s over a huge chunk of the Midwest, and they’re saying billions of cicadas.