Peter Stevens’ Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, which documents the evolutionary relationships of flowering plants and is the only resource of its kind relied on worldwide, earned him the Asa Gray Award. He is a Founders Professor at UMSL and curator of the Missouri Botanical Garden. (Photo by August Jennewein)

Who is Asa Gray? The first North American botanist considered to stand shoulder to shoulder with his 19th-century European counterparts, in particular with Charles Darwin and Joseph Dalton Hooker. Gray’s work to chronicle the plants of a vast and then-undocumented continent earned him such esteem.

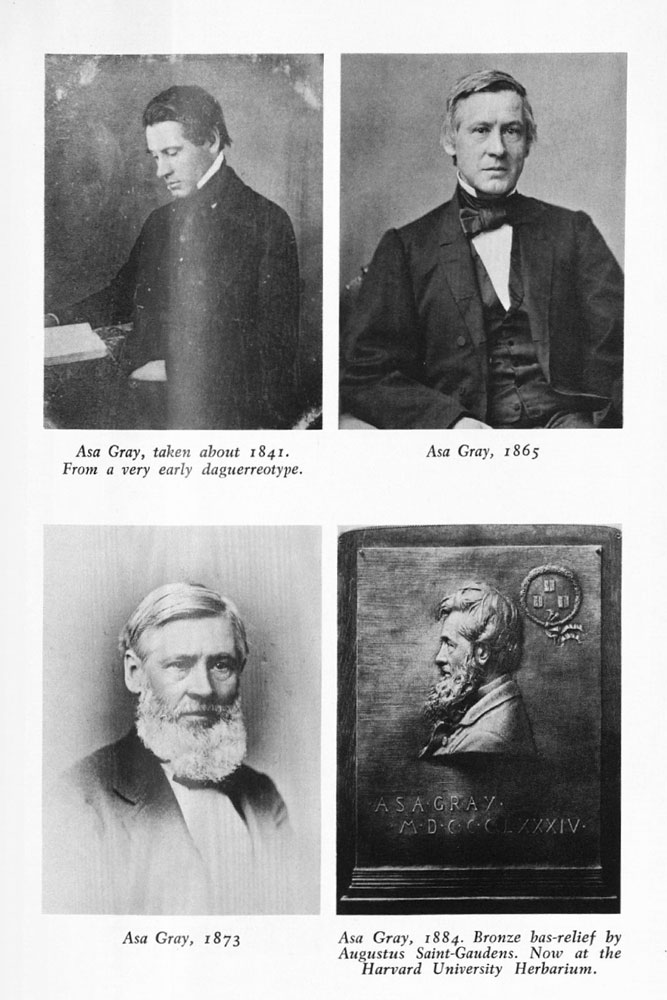

Various portraits of Asa Gray over his lifetime. He lived from 1810-1888. (Photos courtesy of Peter Stevens from the text “Asa Gray” by A. Hunter Dupree, published by The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press in 1959)

So when you ask University of Missouri–St. Louis Founders Professor of Biology Peter Stevens what it means to have won an award named after Gray, he is more than humble.

“Well it means that I shouldn’t have gotten it,” jests Stevens, who is jointly appointed as the curator of the Missouri Botanical Garden and has been there and at UMSL for 17 years. He is also a faculty member of the Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center at UMSL.

Presented Aug. 2 at the garden by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists, the Asa Gray Award honors Stevens’ own chronicling of flora, particularly through his Angiosperm Phylogeny Website.

For non-botanists, that name means his site documents the evolutionary relationships of flowering plants, although he says it’s extended into conifers and their relatives and has begun incorporating mosses as well.

It’s the only website of its sort, making it an extremely important and relied-on resource for botanists worldwide. The idea to create such a resource came to Stevens back in the 1990s when he curated the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University. New ideas about plant relationships started coming about thanks to advancements in the understanding of plants’ molecular makeup.

“I remember thinking, ‘Isn’t it interesting that rhododendron weren’t in Australia?’” says Stevens about the plant family his doctoral work at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland had examined. “We knew this other group of plants that was faintly related existed there, but it transpires that those Australian plants were indeed a branch of the rhododendron family.”

The discovery came thanks to deciphering the plants’ molecular makeup and what it pointed to in their evolution. That got Stevens thinking.

“I thought about doing a website after this for two reasons,” he says. “Number one, there was so much stuff coming out, I thought it would be good if there was some kind of clearing house that people could just sort of access. And number two, it was a way of stabilizing the new concepts, documenting knowledge and using fixed names to talk about evolution, which now one could do because of this massive molecular data. I’m not saying it [the website] solved everything, but it’s a resource.”

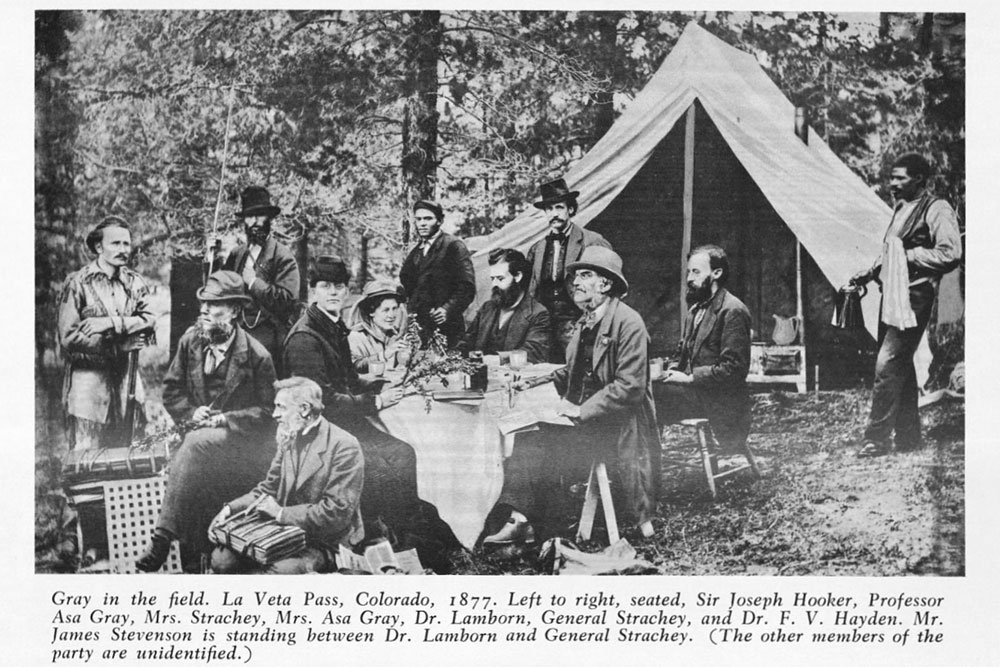

Stevens arrived at the interview for this article with the “Asa Gray” text featuring the esteemed 19th-century botanist in the field. “It was slightly more organized in the field than it is today,” Stevens teased. “You don’t have your local ranger, your guy making coffee and your wife along with you anymore.”

And not only professional botanists use it. There are whole sections of the site aimed at university undergraduate and graduate students.

They can trace the development of molecular variations that lead plants to evolve certain characteristics. Take for example pines, birches and aspens classified as “ectomycorrhizal” because they use fungi to breakdown and extract nutrients from the soil, leaving the sugars for the fungi to feast on.

“These quid pro quo relationships – relatively few thousand species of plants have this,” Stevens says.

Prior to the Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, had Stevens ever dabbled in website design?

“Of course not, no,” he says, laughing. “And the reason I thought of a website to do this kind of thing was that I had tenure. I thought, to hell with publications” – a thought somewhat in line with a young Stevens who once considered doctoral degrees “silly things.”

Although websites are publications of sorts, it certainly was a risk on Stevens’ part – a risk it appears was well worth taking.

He first launched the website, hosted by the Missouri Botanical Garden, in 2001. Currently in its 13th version, Stevens and his graduate student on hand at the time update it fairly constantly. For now, only he has access to edit the site.

“There is an advantage of doing it yourself,” Stevens says, “and that is you know it gets done.”