Eric Vorst has spent the past two years researching human interactions in networked environments with an eye on understanding their implications in the realm of politics, specifically with regard to incivility. He is set to defend his dissertation later this month. (Photo by August Jennewein)

The idea began to emerge, believe it or not, after the St. Louis Cardinals got bounced from the National League Championship Series in 2012.

Eric Vorst logged onto Facebook and quickly started picking up on the hostility that permeated his news feed.

“Everyone was really mad at each other, like fiercely angry, and people were unfriending each other,” Vorst said.

It struck him that there were similarities to the collective mood that can be found after a big election.

Vorst, a doctoral candidate in political science at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, began pondering the attachment people feel to their favorite professional or college teams and how that might translate in the realm of politics.

Several years later, he found himself thinking back to the aftermath of the 2012 NLCS when trying to narrow in on a topic for his dissertation. He decided to examine incivility in social media during the course of the 2016 U.S. presidential election by collecting and analyzing more than nine million tweets related to the politics and the election.

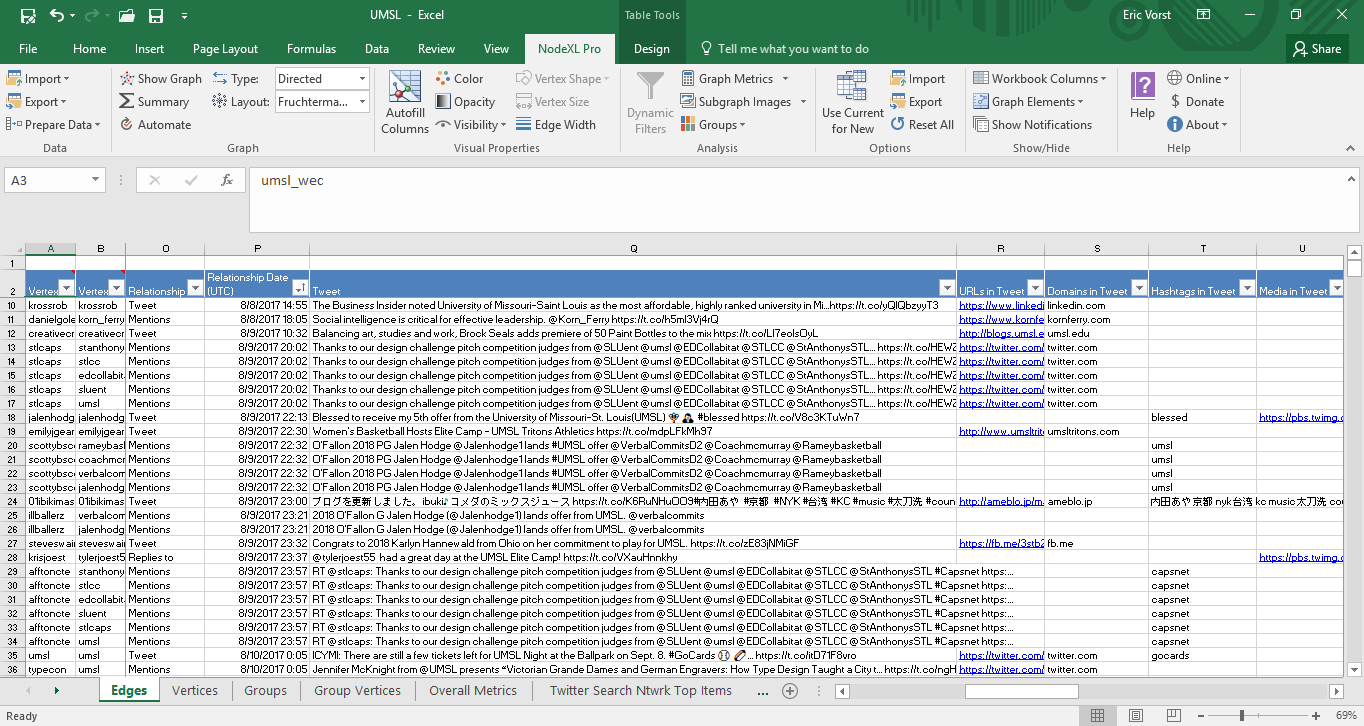

Vorst began gathering all that data – daily now for 721 consecutive days and counting – using a software program called NodeXL in August 2015, months before primary season even started. He looked specifically at the use of affective language and extremely uncivil words and how it fluctuated in proximity to specific political events.

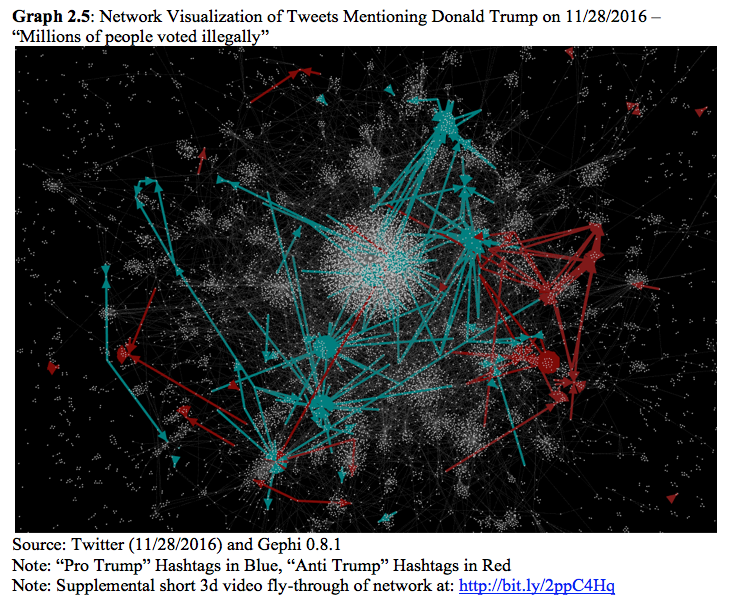

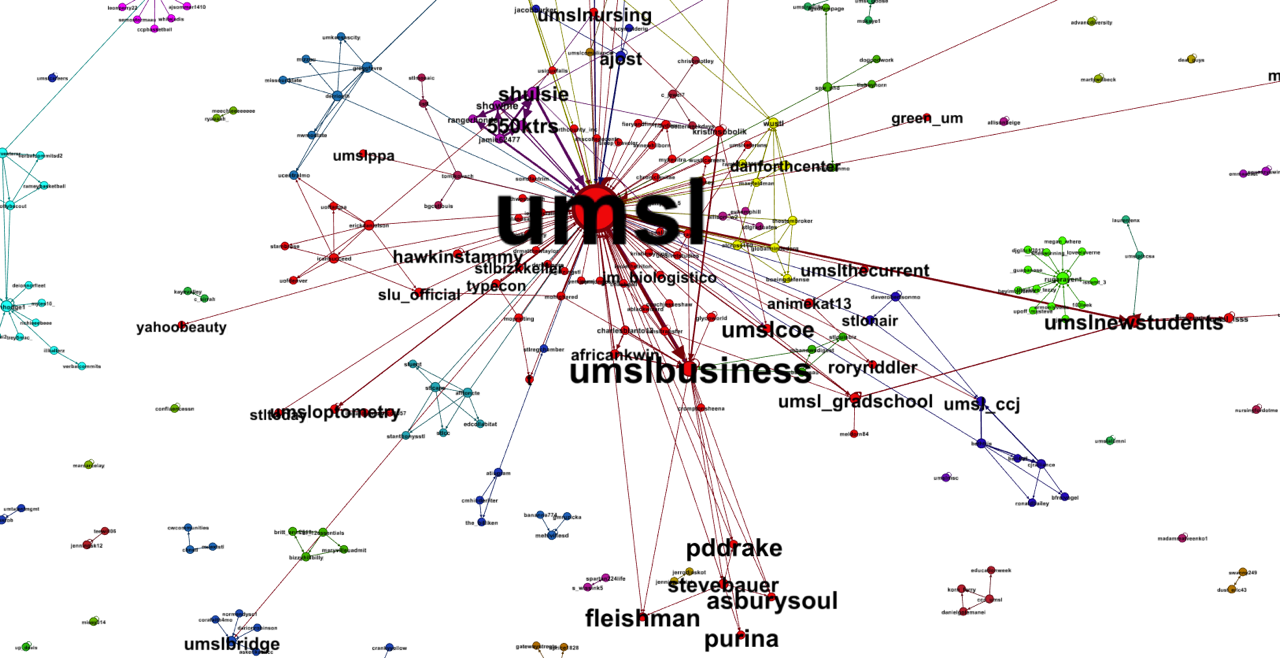

He also mapped networks of users, showing how they were connected and which ones yielded the most influence.

He also mapped networks of users, showing how they were connected and which ones yielded the most influence.

Through his work, he hoped to begin to understand the impact social media has on political participation, civic engagement and deliberative democracy.

“Going into the program back in 2011, I knew I wanted to look at the internet and politics,” Vorst said. “We need to know more about how the internet has affected political participation, how we engage in the political process. There’s potential great benefits and potential great dangers. It’s a powerful medium.

“The further I got in to my doctoral studies, I became more interested in examining the phenomenon of political polarization – how the divisions along Republican and Democratic lines have grown.”

Social media has increasingly been a space where people across the political spectrum interact and sometimes clash.

“He always expressed a lot of interest in contemporary social media and putting it in context,” said Dave Robertson, chair of UMSL’s Department of Political Science and Vorst’s dissertation adviser. “As we continued to discuss this, it became clear to him that he really liked doing this a lot and kept thinking about ways he could innovate in the way we understand social media communications and politics, and the rest is history.”

Part of Vorst’s research has been analyzing networks on social media, specifically Twitter, to understand the way information is shared.

It’s not as simple as counting the number of times a topic gets mentioned the same way researchers have added up the total airtime it might receive on the network news, because information travels differently and users have more control over the sources they connect to and the information they share and receive.

“The social media environment is different than the traditional news media environment, so we can’t use the same tools that we use to study traditional news to study social media,” Vorst said. “They don’t work. It’s kind of like using a flat-head screwdriver on a Phillips head screw. If we use the wrong tools for the job, it not only limits the substantive value of our results but it constrains the types of research questions we can ask.”

Vorst sees an urgency to advancing the understanding of human behavior in networked environments given the rapid emergence of the Internet of Things – with an estimated 50 million devices including even items like refrigerators, thermostats and automobiles expected to be connected by 2020.

“It will undoubtedly impact the relationship between citizens, business, and government,” he said, adding, “We’ve got to develop these tools, so hopefully what I’m doing is at least a step in that direction that somebody else can refine or correct if I’ve made mistakes.”

Vorst envisions, eventually, building a structure that allows people to monitor Twitter and, using an algorithm, answer the question of whether one particular candidate is doing well or another is not.

Vorst envisions, eventually, building a structure that allows people to monitor Twitter and, using an algorithm, answer the question of whether one particular candidate is doing well or another is not.

“People are trying to do that now by saying, ‘Oh, Donald Trump has this many more mentions than Hillary Clinton …’ So what?” Vorst said. “The value of the data is limited, but that’s what you see on the news. That’s what they report, like the frequency of hashtags.”

His vision is still a few years from being realized.

Presently, he has taken the data collected and organized in NodeXL and run it through a network analysis and visualization tool called Gephi. The application allows him to generate three-dimensional models of networks of social media users so that he can observe how neighborhoods of discussions form around different types of messages and with different tones.

His approach helps him illustrate the reach and impact incivility has in social media. He said his work has challenged some of the conventional wisdom of the negative impact of incivility online – namely that it might not hold as much sway as often assumed.

“We don’t know nearly enough about the impact of social media generally, and we’re just learning about that,” Robertson said. “But we understand that it has a huge impact in politics, and you don’t need to go any further than the president’s own Twitter feed to show how important social media is for communicating to people.”

Vorst is a pioneer when it comes to analyzing the connectedness of social media networks, and he demonstrated his methods in a series of YouTube videos while analyzing tweets from last fall’s American Political Science Association Annual Meeting & Exhibition in Philadelphia.

That no doubt contributed to the recognition he received last spring when APSA chose him as its April Member of the Month.

“I was excited about it,” said Vorst, even if he wasn’t chasing attention. “A lot of people work really hard, and sometimes I think you have to get lucky to get seen at the right time.”

“I was excited about it,” said Vorst, even if he wasn’t chasing attention. “A lot of people work really hard, and sometimes I think you have to get lucky to get seen at the right time.”

“It’s a big deal for Eric because it gets his name and his project out to a very large audience who will pay attention to it,” Robertson said. “But it’s also big for UMSL because it gives our university the kind of recognition that it deserves in many fields for innovation, for putting research out there that really can make a difference but then at the same time is very credible to the most theoretical of scholars.”

Vorst is taking part in two panels as this year’s annual meeting, which will take place Aug. 31 through Sept. 3 in San Francisco.

He expects to be finished with his dissertation defense by then, and the meeting could also prove to be a good networking opportunity as he positions himself for what he hopes will be a tenure-track faculty position that allows him to teach at a research university.

“I love to teach,” he said. “I love the learning and the education process and fostering critical thinking in students in a political science class where you’re dealing with really emotional subjects sometimes.

“If my research on social media has taught me anything, it’s that we all need to make a much greater effort to listen to those who disagree with us. We need to discuss our differences in a way that is a little more patient, rational and understanding.”