Sedgwick County Zoo’s new elephant exhibit opened in 2016, not long before UMSL alumnus Jeff Ettling became the zoo’s executive director. (Photo by August Jennewein)

The University of Missouri–St. Louis caught a bit of zoo fever in 2017 as two alumni stepped into executive roles at U.S. zoos.

In May, Jeff Ettling became executive director of Sedgwick County Zoo in Wichita, Kansas, only three months after Kevin Hertell had been named zoo and interpretative services manager at Micke Grove Zoo in San Joaquin County, California.

Half a country away, neither knew of the other UMSL alumnus.

Ettling and Hertell inherited distinct zoos, different in size, animal species and stage of development. But they share an understanding of zoo management – one guided by their biology degrees and a scientific approach to care and preservation of wildlife.

Both will tell you today’s zoos are a far cry from the early menageries of exotic animals collected for kings. The Association of Zoos & Aquariums and educated animal experts like Ettling and Hertell have transformed a zoo’s purpose into one of wildlife conservation.

Sedgwick County Zoo, Wichita, Kansas

Jeff Ettling, executive director, PhD biology 2013

Sedgwick County Zoo Executive Director Jeff Ettling stands along the fence of the new elephant exhibit, which is five acres and boasts the world’s largest elephant pool at 550,000 gallons. (Photos by August Jennewein)

Every day, Jeff Ettling walks Sedgwick County Zoo, visiting the animals and remembering the greater purpose of his work. He wants to ensure that future generations have the same opportunities to experience wildlife as he had growing up.

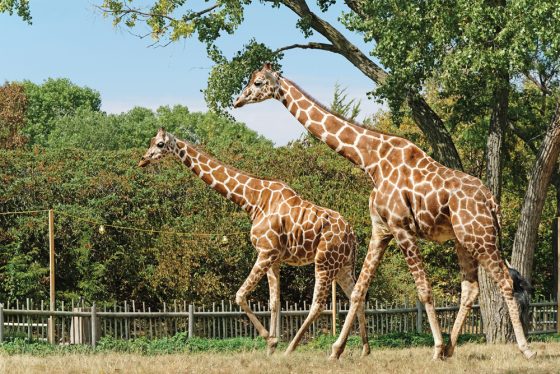

At Sedgwick County Zoo visitors can get an up-close encounter with the giraffes who will often greet people at the fence.

“We know that a child is more likely to develop pro-environmental behaviors if they’re nose to nose with a tiger,” Ettling says. “To do that, we need to get young people to the zoo and make that connection and inspire them to care about wildlife and wild places.”

Conservation is one of the two main goals for the new executive director, who partners with programs locally and internationally to study and protect wildlife. His other goal is renovation.

“We’re going back and looking at things built in the first decade of the zoo’s existence and breathing new life into those exhibits,” says Ettling, who foresees a new, expanded habitat for their Amur leopards and a renovated reptile and amphibian building. “It’s all about animal welfare.”

Built in 1969, Sedgwick County Zoo stands on 247 acres on the west side of rapidly growing Wichita. Over the years, the zoo has made upgrades resulting in the Slawson Family Tiger Trek, Koch Orangutan & Chimpanzee Habitat and a revamped rainforest exhibit.

The biggest renovation came in 2016 with a new elephant exhibit – the third largest in the U.S. It attracted 710,000 visitors the year it opened, surpassing the Wichita metropolitan population by about 80,000 people.

“Sedgwick County Zoo is the top tourist attraction in the state of Kansas,” says Ettling, who calls it “the hidden jewel of the plains.”

Ettling spent the majority of his zoo career as herpetology and aquatics curator for the Saint Louis Zoo, although his time in St. Louis was briefly interrupted for a four-year curator stint at Sedgwick County Zoo in the early ’90s.

An endowed partnership between Saint Louis Zoo and the university, through UMSL’s Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center, allowed Ettling to pursue the PhD he always wanted. He studied Armenian vipers’ spatial ecology and holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

In August, Ettling celebrated three decades of working in zoos.

“If someone had told me 30 years ago that this would be my journey I would have never believed it,” he says, “but it has been absolutely wonderful!”

Micke Grove Zoo, San Joaquin County, California

Kevin Hertell, zoo and interpretative services manager, MS biology 1992

Kevin Hertell, zoo and interpretative services manager of Micke Grove Zoo, holds a Western screech owl. A rescue, like many of the zoo’s animals, an eye injury diminished her chances of survival in the wild. (Photos by Bea Ahbeck/Lodi News-Sentinel)

Kevin Hertell calls Micke Grove Zoo “a little gem” just south of Lodi, California.

Micke Grove’s golden-lion tamarin poses for the camera. The species is named for its golden-red mane reminiscent of male African lions.

Established in 1957, the zoo sits on five acres of Micke Grove Regional Park, named after local philanthropists William and Julia Harrison Micke, and has 170 animals of 49 different species.

It’s all Hertell’s to oversee now as the new zoo and interpretive services manager.

“For local school children, adults and students from two nearby universities, this is their zoo,” says Hertell, who notes that Micke Grove is the only zoo between Fresno and Sacramento.

But before Hertell took over, Micke Grove had gone through tough times, losing AZA accreditation and operating without a manager for three years.

“I did my homework,” Hertell says, “and I saw a situation that could be helped and moved forward.”

This snow leopard is the largest animal to call Micke Grove Zoo home. Snow leopards are a highly endangered animal species.

His reinvigorating leadership and some new funding has spurred improvement projects aimed at gaining back accreditation. Zoogoers can experience a new playground and look for an expanded enclosure for the snow leopard – the zoo’s biggest animal.

Micke Grove also has an unusual inhabitant – a fossa. A relative to the mongoose and unique to Madagascar, fossa are found in only three or four zoos across the U.S.

Like some, Hertell didn’t always enjoy the zoo.

“A lot of times, I would come away feeling sad after seeing the animals,” says Hertell, who recalls the old practice of stealing animals from the wild for display. “But that’s not the way it is anymore.”

Micke Grove Zoo is home to three scarlet ibises. Like flamingos, their brilliant color comes from pigment in the bodies of crustaceans on which they feed.

Zoos like Micke Grove, participate in the AZA’s Species Survival Plan program, helping animals in need and preserving those on the edge of extinction.

Take Micke Grove’s golden eagle, for example. Her damaged wing would have prevented her survival in the wild.

Hertell lives for this type of work and credits his UMSL master’s degree with granting him greater opportunities to do it. He also holds a bachelor’s degree from Missouri State University.

Hertell’s 38-year career with animals – wild and domestic – exposed him to more than 300 species and took him to several states for animal care and environmental specialist work before he ended up at Micke Grove Zoo.

His leadership has good timing too. Micke Grove Zoo just celebrated its 60th anniversary this August.

This story was originally published in the fall 2017 issue of UMSL Magazine. Have a story idea for UMSL Magazine? Email magazine@umsl.edu.