Associate Professor Nathan Muchhala (right) has been conducting field research on the interaction between flowers and the bats and hummingbirds that pollinate them in cloud forests in South and Central America for more than a decade. (Submitted photos)

Nathan Muchhala was doing field research 10 years ago in a cloud forest in Ecuador when he started noticing an unexpected phenomenon.

On more than one occasion, Muchhala, still a fairly young researcher, supported by a National Geographic Society grant while a postdoctoral fellow with the University of Toronto, observed a flower he was studying that had been knocked over, either by a falling branch or an especially stiff wind.

He’d return a day later and see that it had reoriented itself so that even if the stem remained tipped over, the flower had found a way to right itself.

Muchhala collaborated with Scott Armbruster, a professor of ecology and evolution at the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom, on the study. It wasn’t too far removed Muchhala’s primary research focus on the interaction between bats and hummingbirds and the tropical plants they pollinate.

That observation by the now associate professor of biology at the University of Missouri–St. Louis was part of the origin of a new paper titled “Floral reorientation: The restoration of pollination accuracy after accidents,” published earlier this month in the journal New Phytologist.

The paper received attention from websites such as Science Daily, Cosmos Magazine and The Ecologist. The website Science Friday recorded a conversation with Muchhala about its findings and posted it on April 10. The research also found its way into mainstream news when Vox.com writer Brian Resnick wrote about it in a story titled: “This study on flower resilience is the most beautiful thing I’ve read during the pandemic.”

Muchhala couldn’t help but notice.

“It’s amazing,” he said. “All of the sudden, all these people I haven’t heard from in a long time started contacting me.”

When Muchhala first spotted flowers reorienting, he contacted Armbruster, who’d served as the outside advisor on his dissertation committee.

“Oh yeah, I’ve noticed the same thing,” Muchhala remembered Armbruster telling him.

They decided to investigate whether the phenomenon was real. So Muchhala conducted some experiments on flowers in Ecuador and other cloud forests while Armbruster did the same with flowers he was studying in Australia as well as in his backyard in England.

“We had the idea that it should be different for different types of flowers and that more specialized flowers should have evolved to be able to reorient quickly and others should not,” said Muchhala, who came to UMSL in 2013.

That hypothesis was borne out in their research.

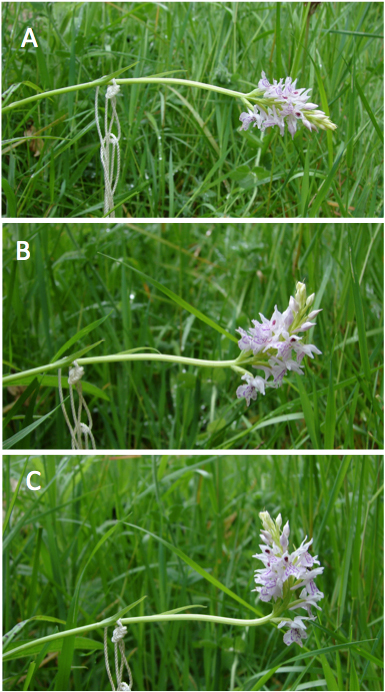

Bilaterally symmetrical flowers, including those in the bellflower family that Muchhala studies as well as its relative the red Cardinal flower, and also Snapdragons and orchids, have demonstrated the ability to reorient themselves when damaged, so long as their vascular tissues remains intact. About a quarter of all flowers are bilaterally symmetrical.

The rest, including flowers such as daisies, are radially symmetrical and do not have the ability to reorient themselves.

“Basically, it’s an adaptation,” Muchhala said. “Flowers, their only function is to try to reproduce, so you’re trying to get your pollen to another flower of another individual, and – for these flowers that are bilaterally symmetrical – you’re putting pollen on a really precise spot. If you put it on the wrong spot, that’s just wasted pollen. It’s never going to make it to another flower. That’s the natural selection. Those flowers that don’t reorient aren’t going to be able to reproduce.”

Muchhala has plans for further research on symmetry and whether bilaterally symmetrical flowers are more efficient at transferring their pollen grains to pollinators.

“With these specialized, bilaterally symmetrical things, it’s still probably low,” he said. “It’s still probably only about 10 percent, but that’s much better than, say, 2 percent for these more generic, generalized flowers.”