UMSL students Elizabeth Allison, Lindsay Davis, Jillian Howell, Delaney Schurer and Alyssa Vargas-Lopez, all pursuing a History MA with an emphasis in Museums, Heritage and Public History, curated the exhibit “Have Blues, Will Travel,” on display now at the National Blues Museum. It highlights the experiences of Black Blues musicians traveling during in the Jim Crow era. (Photo by Steve Walentik)

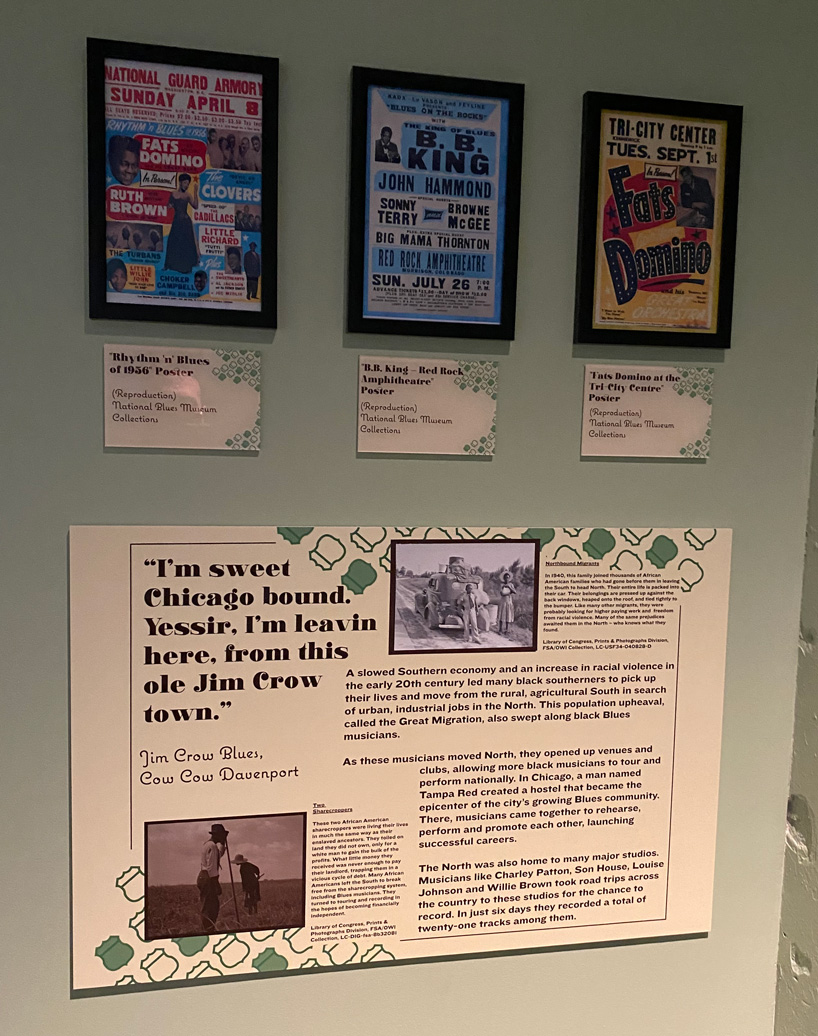

The Black Blues musicians of the early to mid 20th Century typically had to hit the road to make a living, traveling around the country to perform, sometimes in large halls and theaters and other times in backwoods bars and juke joints.

Recording contracts were rare, so they relied on the money generated from live audiences to sustain them. But, as a new exhibit at the National Blues Museum in downtown St. Louis shows, travel to and from shows was not without risk in the age of Jim Crow.

“Have Blues, Will Travel” details some of the experiences of Black performers on the road during segregation and into the 1960s. It also spotlighted the importance of guidebooks like the “Negro Motorist Green Book” and “Travelguide” in helping them navigate by pointing to friendly gas stations, restaurants and hotels.

A group of five University of Missouri–St. Louis graduate students, each pursuing their History MA with an emphasis in Museums, Heritage and Public History, curated the exhibition. In one instance, they included the experience of singer Fontella Bass, who after the success of her 1965 hit song “Rescue Me” found herself staying in a hotel in Pulaski, Virginia, with her husband.

“You guys is the first n—— that stayed up in the Howard Johnson,” the hotel manager told her.

Fontella later remembered that fearful night.

“We was looking at the tree out there, which one they gonna hang us at,” she said.

UMSL students Jillian Howell, Delaney Schurer and Alyssa Vargas-Lopez attended the exhibit opening in December at the National Blues Museum. (Photo courtesy of Andrew Hurley)

The students – Elizabeth Allison, Lindsay Davis, Jillian Howell, Delaney Schurer and Alyssa Vargas-Lopez – share other accounts gathered from research they did for the Practicum in Public History and Cultural Heritage course they took last spring under the direction of Professor Andrew Hurley.

“We offer several practicum-based courses in the curriculum, where students get their hands dirty and work in real-life situations outside of the classroom,” Hurley said. “They get to do stuff that they will be doing in their careers as museum and heritage professionals.”

In previous years, UMSL students have worked on exhibits for the Missouri Historical Society or The Griot Museum of Black History.

Last spring was the first time Hurley partnered with the National Blues Museum, though the museum, opened in 2016, has hosted UMSL students, including Vargas-Lopez, for graduate fellowships.

Erin Mahony, the deputy director of the National Blues Museum, came up with the idea for an exhibit connected to the “Negro Motorist Green Book” after a movie, “Green Book,” captured the Academy Award for Best Picture in 2019.

“I thought it’d be recognizable to audiences,” Mahony said. “They might be familiar with it from the movie, and I thought it might pique the interest of the students. From a conversation with Dr. Hurley, I threw out a couple ideas. I think that was something that the students were interested in.”

The movie tells the story of a classical pianist, not a Blues musician, but it brought attention to the travel guide first published by New York City mail carrier Victor Hugo Green in 1936 and updated regularly until 1966. At its height, the guide had a circulation of more than 2 million.

The students used reprints of old concert posters and lyrics from Blues songs to help tell the story of what Black musicians experienced as they traveled and performed. (Photo by Steve Walentik)

The students spent weeks learning about people who relied on the guide, which came with the tagline: “Carry your Green-Book with you … You may need it.” They scoured old newspapers, particularly from the Black press, and read autobiographies of Blues musicians who rose to prominence during that period, while also collecting lyrics from Blues songs to incorporate into the exhibit.

“The key to making this work, particularly with only five students in the class, was dividing the responsibilities,” Hurley said. “People worked in teams or even independently, so all the research tasks were divided. There was a lot of photographic research. We divided up the archives. One student would go through Library of Congress images. Another student would see what was at the Missouri Historical Society.”

Mahony and her colleagues also connected them with Blues musicians and others who were part of the industry, including one woman who worked with Albert King, to ask them about their own experiences out on the road.

“That was some crucial information, just to get that one-on-one perspective, that first-person perspective on what had happened,” Vargas-Lopez said. “Without that, I don’t think we really would have had the real feeling behind the exhibit, had that emotional push that we did for our final product.

“It also helped it all hit a little harder. This was not even 100 years ago, and we should take it more seriously, that we should talk about it more. Because it is so close to us, and we’re still going through the process of getting rights and preventing discriminatory practices.”

Indeed, they even connected the exhibit to the present day by pointing to violence committed against Black citizens, including motorists, and highlighting the activism of St. Louis rapper Tef Poe.

Vargas-Lopez and her classmates were fortunate to finish their interviews and the bulk of their other research early last March, right before COVID-19 halted everyday activities across the country.

With UMSL’s campus closed and classes shifted online for the remainder of the spring semester, they had to finish the work for the exhibit remotely. That included writing the exhibit panels, shopping for the different types of display cases and negotiating with printers.

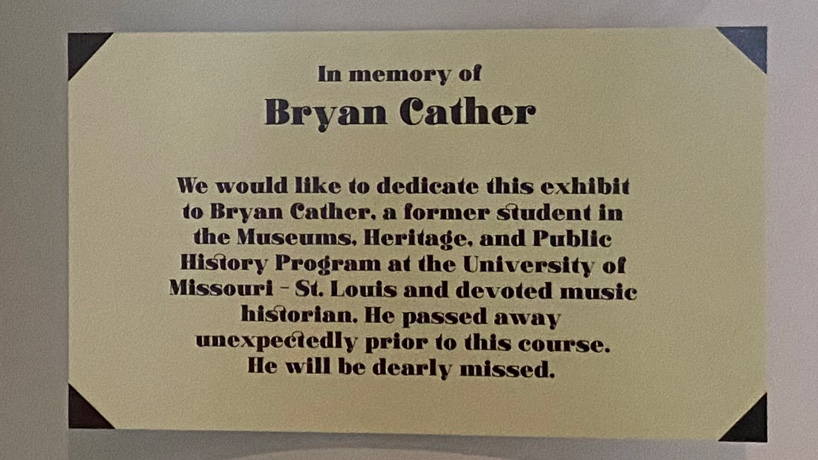

The exhibit was dedicated to Ragtime researcher Bryan Cather, who was to be a student in the course but died suddenly on Jan. 4, 2020, only a few weeks before the start of the spring semester. He was 53. (Photo by Steve Walentik)

They engaged with each other via email and in Zoom meetings and again divided up the tasks, trying to match each with an individual’s strengths.

The exhibit had originally been slated for a May opening, but city orders kept the National Blues Museum closed until late in the summer. Museum staff took charge of setting up the exhibit, and the students had their first chance to view it during a scaled-down opening in mid December.

“To see the work was amazing,” Vargas-Lopez said. “All the other shows I had been part of before didn’t have framed photos or artifacts. So to be able to see those on the wall, to see that we collected those and we were able to go through that process – it was another thing checked off my box. It was like ‘I’m moving forward.’”

Mahony and her colleagues are equally pleased by the results.

“We’ve had a really great experience with UMSL,” she said. “We’ve had a great experience with our fellows. We had a great experience with that class. We would love to just continue the relationship and partnership, and we’ve been really impressed with the students that have come.

“They’ve been extremely professional. They’re really eager and excited about working in the field. They’re very thoughtful and conscientious, especially about issues in the modern museum today. The work ethic of the students who come from UMSL is just exceptional.”

“Have Blues, Will Travel” will remain on display at the National Blues Museum until August and is included in the $15 admission. For museum hours and to purchase tickets, visit nationalbluesmuseum.org.