Patricia Parker, the E. Desmond Lee Endowed Professor in Zoological Studies, was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. (Photo by August Jennewein)

Patricia Parker was ready to dismiss the message informing her of her election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences when it arrived in her inbox.

She figured it was the latest in a line of unsolicited emails inviting her to join different groups or to submit articles, often from journals with names she didn’t recognize.

But then other emails started showing up from people she did know, offering words of congratulations and admiration for some of her career accomplishments, and Parker, the E. Desmond Lee Endowed Professor in Zoological Studies at the University of Missouri–St. Louis and a senior scientist at the Saint Louis Zoo, began to reconsider.

“I started getting messages from current members, people who are big names in the field, and I realized that it was real,” she said. “I’m so stunned and proud.”

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences welcomed 252 new members – including 10 in Evolution and Ecology – on April 22.

Founded in 1780, the academy honors excellence and convenes leaders from every field of human endeavor to examine new ideas, address issues of importance to the nation and the world, and work together, as expressed in its charter, “to cultivate every art and science which may tend to advance the interest, honor, dignity, and happiness of a free, independent, and virtuous people,” according to its website.

Among its founders were American Founding Fathers John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, and its membership over the years has grown to include luminaries in a wide array of fields such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Jonas Salk, Charles Darwin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Toni Morrison and Nelson Mandela.

Parker has enjoyed a long and distinguished career as an evolutionary biologist, working most frequently with avian populations. She has received more than $4 million in grants for research and other projects and has authored or co-authored 200 articles in peer-reviewed journals with collaborators from around the world.

She also has mentored 50 graduate students from 10 countries who have gone on to work in academia, with nongovernmental organizations or in policy-making positions during nine years as a faculty member at The Ohio State University and 21 years at UMSL.

Parker has been a member of numerous professional societies, including a fellow of the American Ornithological Society, the Animal Behavior Society, the Academy of Science of St. Louis and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The Jennings School District awarded Parker its Exemplary Education Partner Award for her work with the Collaborative Laboratory Internships and Mentoring Blueprint.

Among her many awards is the Order of Scientific Merit she received from the citizens of Galápagos in 2008, the Stephen J. O’Brien Award from the American Genetic Association the same year, the Saint Louis Zoo Conservation Award in 2014, the Brewster Memorial Medal from the American Ornithological Society in 2016 and the Exemplary Educational Partnership Award from the Jennings School District, awarded last year but presented this April, for her work leading the Collaborative Laboratory Internships and Mentoring Blueprint.

Parker is already looking forward to the annual induction weekend for this latest honor from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. It is slated for next spring.

“My family wants to go,” Parker said. “My grandkids want to go. My sisters from all over, they want to go. So that’s going to be fun.”

The news of her election has also led her to reflect on all she’s accomplished since she was a student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, earning her bachelor’s degree in zoology in 1975 and her PhD in biology nine years later.

Parker spent six years as a visiting scholar and research scientist at Purdue University after earning her PhD. She worked frequently with longtime friend Ellen Ketterson, a faculty member at Indiana University, and was one of the first people to take just-emerging genetic techniques and apply them to wild animal populations.

“We learned some very interesting things,” Parker said. “But I think, more than that, the characteristic that I’m proud of is having a sort of fearlessness that if there’s somebody in the world that is doing something, then I can do it too.”

Her expertise, along with her willingness to explore new avenues, opened up doors for future collaboration with other scientists, first at Purdue and then as a member of the biology faculty at The Ohio State University from 1991-2000.

By the early 1990s, she started collaborating with John Faaborg, an ornithologist at the University of Missouri–Columbia noted for his research on Galápagos hawks. Parker conducted genetic testing to better understand the relationships between females and males living in polyandrous groups.

With their preliminary data, she and Faaborg eventually secured a National Science Foundation grant that provided Parker her first chance to do research in the iconic islands in 1998.

Two years later, she came to UMSL to serve as the E. Desmond Lee Endowed Professor in Zoological Studies, a position that came with a dual appointment at the Saint Louis Zoo.

She’d been prepared to take her research in a different direction and, perhaps, to a different part of the world, but the Zoo supported her continued work in Galápagos through its WildCare Institute.

“I really helped the zoo expand their studies in nature,” Parker said. “Not that they weren’t doing any, but they weren’t doing very many, and they weren’t doing them in a very organized way. But for me, that was new. I’m not a veterinarian. We just kind of worked together, and I picked up these skills, and we took another turn toward application of a new set of skills to a new set of problems.”

Parker, who also serves as the interim director of UMSL’s Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center, estimates she’s made about 30 trips to the Galapagos Islands, her research shifting to disease ecology with a particular focus on avian malaria.

In what she considers the most important adaptation in her career, Parker has put much of her attention over the past 15 years to opening access and building capacity among individuals who for too long felt cut off from working in science.

That began in Galápagos, where she helped train some of the Ecuadorians living in the islands to conduct health tests and do other research on the wildlife there.

After the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson in 2014, Parker found herself motivated to unlock opportunities for students much closer to the UMSL campus who’d been marginalized.

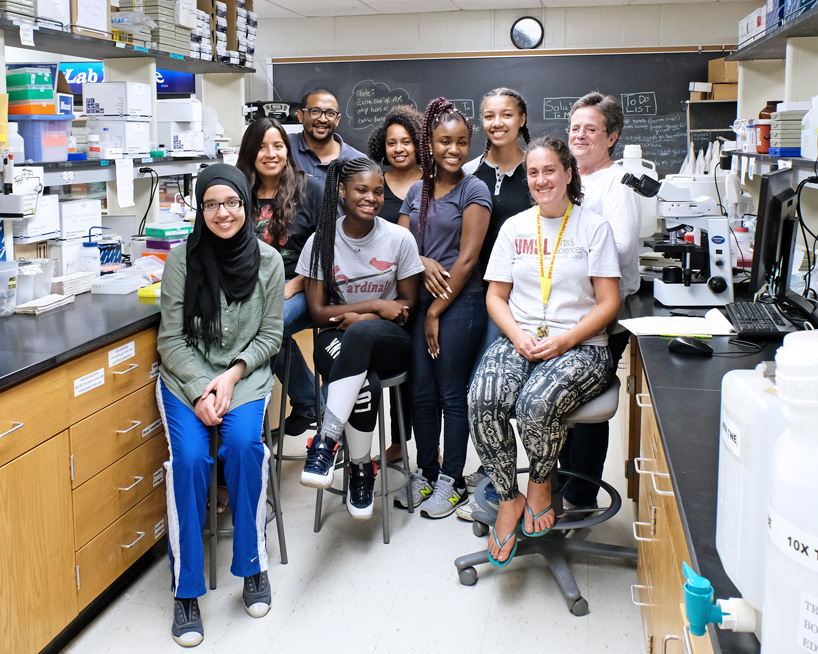

The CLIMB program has been providing paid internship opportunities to high-ability but low-opportunity students since its founding in 2015.

Parker created the Collaborative Laboratory Internships and Mentoring Blueprint or CLIMB program as a joint effort between UMSL and the Jennings School District. It has since expanded to serve students at University City High School, Ritenour High School and Riverview Gardens High School.

The program provides a paid summer internship program for high-ability but low-opportunity students, who spend six weeks – 40 hours per week – working in research groups and getting hands-on lab experience in chemistry, biology, physics, psychology, education, mathematics and computer science.

“The big goal is to see them emerge with the confidence to know that whatever they decide to do, they can do it,” Parker said. “They just have to try hard, and they have to find the right people and establish the right relationships.”

Parker was lucky to grow up with a great sense of independence, much of it coming naturally to her as a middle child.

But she also reinforced it late in her undergraduate career when she abruptly quit school and spent her last $300 on a plane ticket to Italy. Parker eventually found work at a naval base in Naples, saving up her money for two years, before living out of her car for a year as she traveled around Europe.

“I think that that did something to me that no matter what, I was going to be OK, and I could just do what was most interesting to me,” said Parker, who went back to North Carolina to finish her bachelor’s degree after the experience.

It’s why she was willing to take risks early on in her doctoral research as she studied vultures, and also why she’s been so willing to shift gears so often throughout her career since.

In that way, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences seems like the perfect organization for Parker to be part of.

“It’s arts and science,” Parker said. “It’s everything. It is not just focusing in on accomplishments or excellence or achievement or whatever in a particular area. It’s trying to get people who know how to do things from a variety of perspectives and get them together to potentially solve even larger problems. I think that is so cool.”