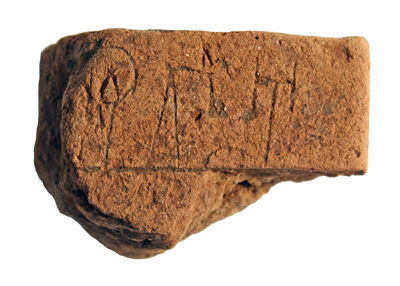

A 2 inch by 3 inch tablet was discovered in Iklaina, Greece. It’s the oldest known tablet in Europe. The back of the tablet is pictured. (Photo by Christian Mundigler)

The oldest written record in Europe was discovered during a recent excavation in Greece by University of Missouri–St. Louis archaeologist Michael Cosmopoulos. The find changes what is known about the origins of literacy and bureaucracy in the Western world.

Measured at 2 inches by 3 inches, the tablet fragment is thought to date back to between 1450 and 1350 B.C. – 100 to 150 years before the tablets from the Petsas House at Mycenae.

“I was in disbelief,” said Cosmopoulos, the Hellenic Government Karakas Family Endowed Professor of Greek Studies at UMSL and director of the Iklaina Archaeological Project, which he has directed for 11 years. “According to what we knew, that tablet should not have been there.”

The rare artifact was unearthed last summer during the UMSL excavation at the site in Iklaina, which sits in the middle of an olive grove in southwest Greece. It is being published this April in the upcoming issue of “Proceedings of the Athens Archaeological Society” and presented in a formal lecture by Cosmopoulos in the Missouri History Museum at 7:30 p.m. on April 12.

Iklaina dates to the Mycenaean period (ca. 1500-1100 B.C.), an era famous for such mythical sagas as the Trojan War. It was one of the capital cities of famed King Nestor, who figures prominently in Homer’s “Iliad.”

“This is a rare case where archaeology meets ancient texts and Greek myths,” Cosmopoulos said.

The Mycenaeans used clay tablets in their palaces to record state property and transactions. These tablets are written in the Linear B system of writing, which is older than the alphabet. It consists of around 87 syllabic signs. These signifying signs stand for objects or commodities and the tablets are mostly lists of property and accounting records. Archaeologists are still studying the Iklaina tablet, but preliminary analysis suggests it may refer to some sort of manufacturing process.

“On the front there is a verb that relates to some sort of manufacturing,” Cosmopoulos said. “On the backside, there is a list of men’s names alongside numbers.”

Tablets like this one were not meant to be kept more than a year and as a result were never sent to a kiln, he said. They are preserved only if accidentally burned, which is the case of the Iklaina tablet.

“This discovery is the biggest surprise in years of excavation. It was found in a burned refuse dump dated to between 1450 and 1350 B.C.,” Cosmopoulos said. “The tablet is only the latest in a series of discoveries at Iklaina. In the last two years, the excavation has brought to light evidence for the existence of an early Mycenaean palace: elaborate architecture, massive ‘Cyclopean’ terrace walls, colorful murals and a drainage system far ahead of its time.”

These pieces are indicative of a major center, potentially an early Mycenaean state capital. Cosmopoulos is cautious, however, and said that it is too soon to tell whether Iklaina was one or not. Currently, there is only a handful of known major state capitals, such as Pylos and Mycenae.

“Iklaina could potentially challenge what we know about the origins of states in ancient Greece,” Cosmopoulos said. “Not only does it push the origins of those states back in time by at least a century and a half, but the tablet shows that literacy and bureaucracy appeared earlier and were more widespread than what we had thought until now. We still have a lot to learn about the ancient world.”

Each summer Cosmopoulos returns to the dig site with a team of about 40-60 students from UMSL and other universities and 25-30 staff and specialists. The land of the excavation was purchased on behalf of the Greek government, and by law all the finds remain in the local museum as property of the Greek state.

The dig is funded with grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Geographic Society, the Institute for Aegean Prehistory, Harvard University, the Pylos Archaeology Foundation, and the Center for International Studies at UMSL.

More information:

cosmopoulos@umsl.edu

iklaina.org