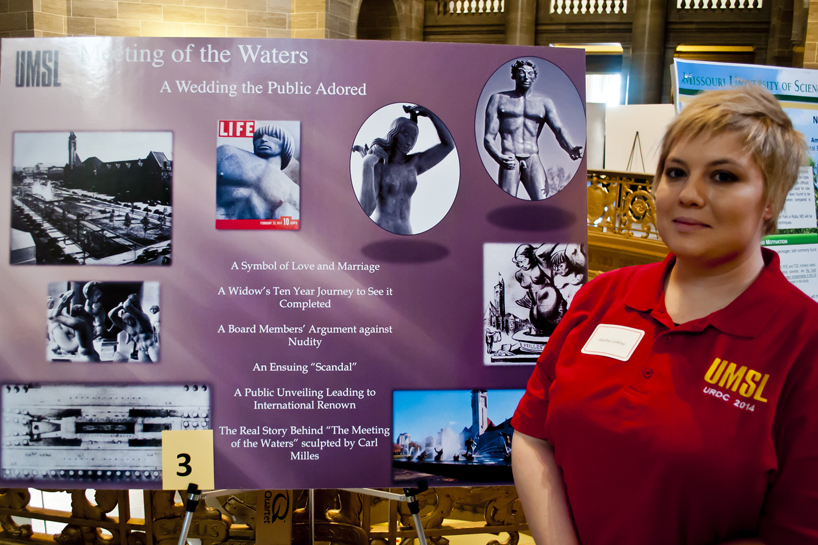

UMSL senior Alysha LeMay presented her research project about “The Meeting of the Waters,” a St. Louis sculpture by Carl Milles, at the University of Missouri Undergraduate Research Day at the Missouri State Capitol. (Photo by David Champlin)

More than two decades before the Gateway Arch was completed, downtown St. Louis was already a destination for a famous sculpture.

“The Meeting of the Waters” by Carl Milles drew the eyes of many tourists in Aloe Plaza as they exited Union Station on to Market Street. Today, the grand fountain is something that many visitors to downtown have seen in passing, but few stop to study it or research its history.

University of Missouri–St. Louis senior Alysha LeMay decided to study the fountain and its significance for an art history class. As a result, her work was included in the University of Missouri’s Undergraduate Research Day held earlier this month at the Missouri State Capitol. The event allowed students to display their research endeavors and discuss their projects with legislators. Serene Darwish, a UMSL senior who was profiled by UMSL Daily in May, also presented her work in biology. Most projects were science-based, but LeMay focused on an aspect of St. Louis history that is often overlooked.

“At the time it was unveiled it was considered a huge coup for St. Louis to have something that prominent,” said LeMay, an art history major. “People would come from all over to see it, similar to the Arch now.”

The piece consists of two people standing in a pool, followed by water creatures such as mermaids and catfish. The two main figures, a man and a woman, symbolize the Mississippi and Missouri rivers that shaped the St. Louis region geographically and economically. Each figure in the piece has its own spout, which was considered cutting-edge technology at the time.

Milles was a Swedish sculptor and student of Auguste Rodin, and developed a new style of sculpture. His work can be seen worldwide and elsewhere in St. Louis, including several pieces at the Missouri Botanical Garden. There was so much publicity over the fountain that Life Magazine did a pictorial chronicling its production.

LeMay’s project focused on the disconnect between the way the piece is often described by contemporary writers and the public sentiment of the time. She consulted primary historic documents that chronicled the piece from the proposal stage to its public unveiling in the spring of 1940.

Milles created “The Meeting of the Waters” after being approached by Edith Rosenblatt Aloe, who wanted to finance a sculpture in St. Louis honoring her husband, Louis P. Aloe, a former president of the St. Louis Board of Aldermen. The idea of a public sculpture received support as a way to benefit downtown, and a council was formed to oversee its design and installation.

Two council members who visited Milles’ studio objected to the fact that the figures were nude and the piece originated with the title “The Wedding of the Waters.” Milles agreed to change the title, and the nudity received little fanfare after that, according to documents of the time. But many modern discussions make it sound like there was a public outcry regarding the main figures’ states of undress.

“I feel like the focus on the nudity doesn’t give the piece the respect it deserves,” LeMay said. “When we talk about these things, we need to be factual.”

Documents from the time show that the public was more concerned that the fountain featured a European aesthetic rather than American images like pioneers and Indians.

“It was supposed to be something grand to reflect the significance of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers,” LeMay said. “Milles also wanted to capture the love story of this wife and her husband.”