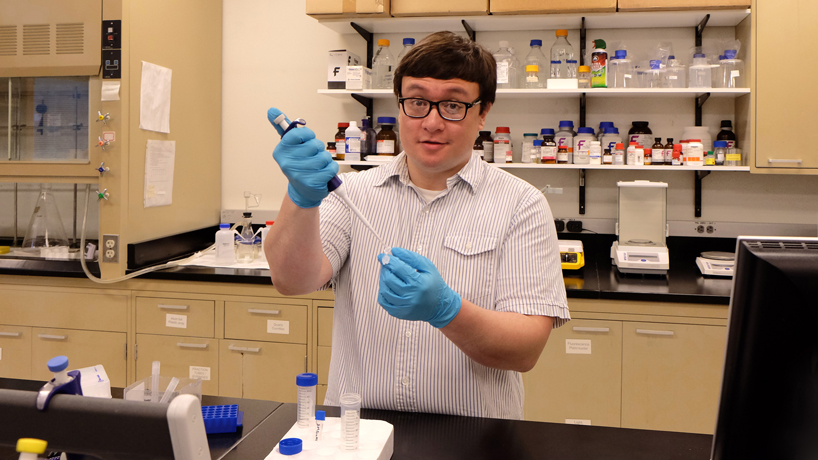

Senior Richard Davenport is one of nine recent recipients of an undergraduate research grant at UMSL. (Photo by August Jennewein)

Misfolded amyloid-beta proteins, inflammatory responses, absorbance ratios – it sounds complicated because it is, admits Richard Davenport, a University of Missouri–St. Louis senior majoring in biochemistry and biotechnology.

“At times it’s overwhelming, the amount of information you have to process on a daily basis,” Davenport said. “Research can be daunting and even monotonous sometimes. You have to do the same kinds of things many times to verify things, to show trends. It takes a lot of patience.”

Davenport has learned this firsthand while conducting research related to neurogenerative diseases. One of nine undergraduate students who were awarded a $1,000 research grant from the College of Arts and Sciences this spring, his project involves the nitty-gritty of protein aggregation, long associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

“We are looking at the different types of species that are formed as a result of amyloid-beta protein aggregation,” Davenport said. “They bind to the immune cells in the brain and initiate this signaling cascade – inflammation – that causes the body to attack good cells.”

That protein is the main focus of work in a UMSL lab overseen by Associate Professor of Chemistry Michael Nichols. Eventually accumulating to form senile plaques or deposits in AD brains, the proteins are naturally occurring but not well understood. Davenport is measuring the amount of inflammatory signaling molecules produced along the way.

“It’s a long, complicated chain of events,” Davenport said. “We’re looking at that chain of events. If we can understand the protein and these stages, we can look and see what points there are for possible therapeutic intervention.”

On top of coursework for his major and the six to 12 hours a week Davenport devotes to Nichols’ lab, he also puts in roughly 15 hours each week at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, working as an assistant in a lab investigating algae. Diving into research as an undergrad has enabled him to make sure it’s something he wants to do. After he graduates next May, he plans to continue on to grad school and pursue a PhD.

Davenport spent about a decade in corporate communications before making what he describes as “a 180-degree switch” and enrolling as a science major at UMSL in 2011. He enjoys the intellectually stimulating nature of research and the way science seeks to advance knowledge of the world.

“The bottom line is not the key thing that’s driving us,” he said. “Learning things, discovering things, advancing our understanding of the world – that’s the driving force in a research lab.”