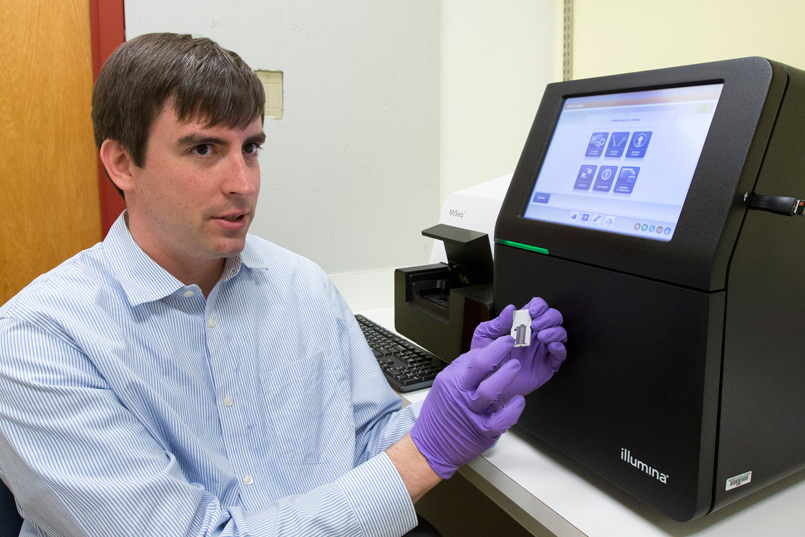

Michael Hughes, assistant professor of biology at UMSL, co-authored a study on gene expression published Oct. 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. (Photo by August Jennewein)

Findings of a study co-authored by a biologist at the University of Missouri–St. Louis provide important clues about how the role of timing may influence the way drugs work in the body.

The research, led by John Hogenesch, professor of pharmacology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, mapped 24-hour patterns of expression for thousands of genes in 12 different mouse organs. The study detailing this veritable “atlas” of gene oscillations, never before described in mammals, was published Oct. 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team found that nearly half of all genes in the mouse genome oscillate on a 24-hour schedule somewhere in the mouse body. They determined that the majority of best-selling drugs in the U.S. target proteins made from genes whose expression changes daily.

“It’s been recognized for a long time by some really intelligent people that when you take a drug makes a huge difference on how effective it is or how severe your side effects are,” co-author Michael Hughes, an assistant professor of biology at UMSL, said in an interview with The Scientist. “I think that we take that field a big step forward because now we can take a look at that phenomenon … in a whole-organism and a whole-transcriptome scale, so we can predict which drugs are most likely to be influenced by time.”

Hughes is a former postdoctoral researcher in Hogenesch’s lab.

The team suggests that the intersection of atlas and drug data can predict which drugs might benefit from timed dosing – “the essential medicines that directly target the products of rhythmic genes and therefore proteins.” This approach is the crux of a growing field of study called chronotherapy.

Specifically, the team found that 43 percent of all protein-coding genes showed circadian rhythms in being transcribed into proteins somewhere in the mouse body.

The study has implications for 100 top-selling U.S. drugs, half of which target daily-oscillating genes. Fifty-six of the 100 top-selling drugs and 119 of the 250 World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines work on genes with circadian oscillation.

The study of drug timing has been going on for 40 years and has had several successes like chemotherapeutics, short-acting statins, and low dose aspirin. However, most of these studies were done by trial and error.

“Now we know which drug targets are under clock control and where and when they cycle in the body. This provides an opportunity for prospective chronotherapy,” explained Hogenesch.

Benefits of proper drug timing could include better compliance, improved efficacy, fewer drug-to-drug interactions, and ultimately, better outcomes at lower costs.

Funding for the research came from a National Institutes of Health grant and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Media Coverage:

The Daily Telegraph

The New Zealand Herald

ScienceDaily

Tech Times

The Australian

Times of Malta