UMSL graduate student Emily Anderson (center) explores the portrayal of disabled characters in contemporary children’s literature through an exhibit created by fellow student Kelly Sutton. (Photos by Evie Hemphill)

A new course this fall pushed English graduate students at the University of Missouri–St. Louis to not only delve deep into a topic often dismissed as uncomfortable, but also keep the conversation going beyond the classroom.

Offered by Assistant Professor of English Lauren Obermark, the graduate seminar explored disability as an identity category that is a fundamental part of the human experience, similar to race or gender.

“The seminar has pushed me to question assumptions about disability, such as the stereotypes that to be disabled is tragic, different or something that needs pity or charity,” said class participant Lauren Terbrock, who created an online annotated bibliography on the overlap between disability and gender studies. “Those assumptions make disability sort of difficult to talk about.”

A course like Obermark’s creates a space where that unease fades away, she said, providing room to grapple with the implications of such stigmatization.

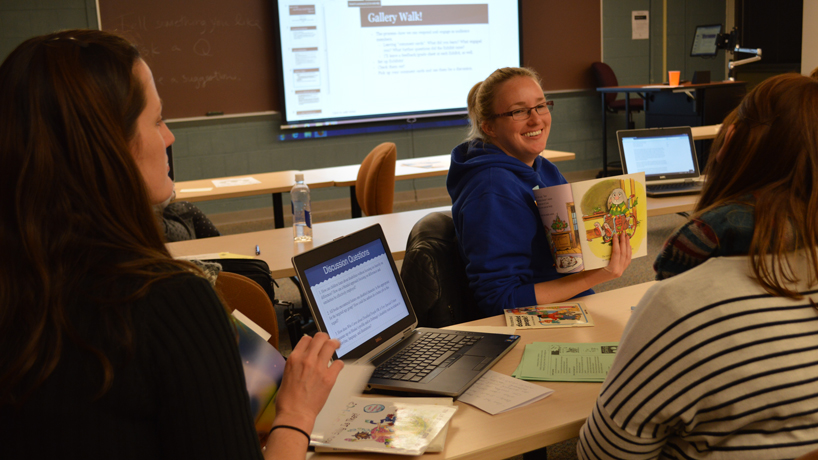

Assistant Professor of English Lauren Obermark (at right) wrapped up her English graduate seminar – The New Normal: Introduction to Disability Studies – with a “gallery walk” featuring the students’ interactive final projects.

“We get over the awkwardness and talk about it,” Terbrock added. “We open ourselves up and say, ‘Yes, I’ve thought these things to be true.’ But then we use those moments as a turning point where we can question everything and seek out a better understanding of disability.”

That better understanding was on full display at the final class session Dec. 11, with the 10 graduate students putting on a “gallery walk” showcasing their final projects. The creations ranged from analyses of public policy and depictions of disability in pop culture, to new online resources for teachers, to videotaped interviews with disabled people.

“These students are immensely smart and thoughtful, and they’ve done incredibly great thinking all semester,” Obermark said. “Many of them are current teachers, so they should have nuanced understandings of disability. And all English grad students are equipped with strong analytical skills that they can bring to bear on these big questions.”

Throughout the semester, the group investigated the social and political dimensions of disability. They explored common assumptions, how the field of disability studies can contribute to change, and ways to keep the voices of disabled people at the center of such inquiry.

The diverse approach to the students’ final projects is one example of how disability studies has changed Obermark’s own pedagogy, she said.

“I’ve been playing around with different ways to do presentations,” Obermark said. “I used to just do standard 10-minute research presentations to end courses I taught. But the students didn’t seem to like them or learn much from them, and I felt bored with it, too.”

UMSL graduate student Lisa Clark watches videos created by her classmate Jami Hirsch during the final session of an Introduction to Disability Studies seminar.

Drawing on a teaching approach known as universal design for learning, Obermark decided to ask her students “what works for them” when it comes to receiving and communicating information.

“I asked them how they thought we could make the sharing of our final projects work, and then we designed a way to do it that let students share in various ways – from short films, to websites, to traditional trifolds,” Obermark said. “The results were thought-provoking and exciting.”

Recently named a 2015 Disability in College Composition Travel Award recipient, Obermark will present her research about using disability studies concepts in graduate courses at the Conference on College Composition and Communication in the spring.

A related case study, “Mad Women on Display: Practices of Public Rhetoric at the Glore Psychiatric Museum,” will appear in the December 2014 issue of Reflections: A Journal of Public Rhetoric, Civic Writing, and Service Learning.

“That article merges two of my research passions – disability studies and rhetorical analysis of museums,” Obermark said. “I argue that such disability museums frequently inform, and hopefully change, public knowledge and discourse about disability, which remains conflicted, misinformed and even unethical – especially when it comes to mental disability.”