“What can we do outside the legal realm to change our society to be more inclusive and equitable?”

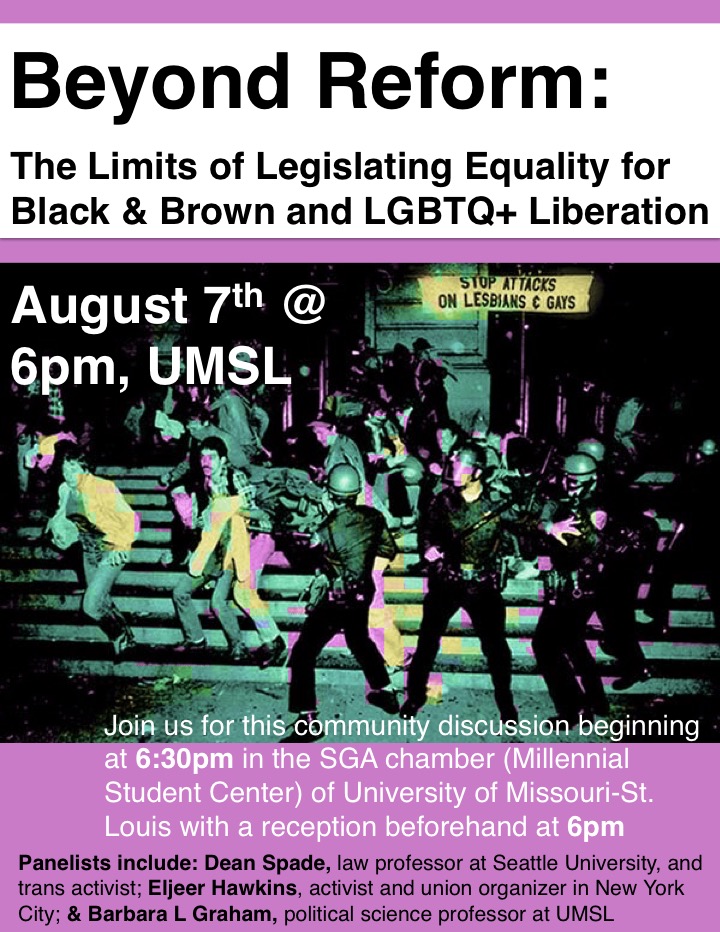

That question is at the center of an upcoming panel discussion at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, says Assistant Professor of Anthropology Sarah Lacy, who will moderate the Aug. 7 event.

Assistant Professor of Anthropology Sarah Lacy will moderate the Aug. 7 panel in the Millennium Student Center. (Photo by August Jennewein)

“Beyond Reform: The Limits of Legislating Equality for Black & Brown and LGBTQ+ Liberation” will explore ways that various groups subject to discrimination can work outside purely legal channels – and collaboratively – to achieve equality in society. The 6:30 p.m. discussion will take place in the SGA Chamber of the Millennium Student Center.

“We all suffer when one suffers, and by embracing the struggles of other communities, our protest spaces become diverse and also safer,” Lacy says. “We should not abandon legal battles and political ambitions, and we should continue to push political candidates to adopt platforms that lift up the oppressed. But we also need to think about how we affect public consciousness more directly, and that is partially the point of this upcoming community discussion.”

Panelists will include Barbara L. Graham, an associate professor of political science at UMSL; Eljeer Hawkins, an activist and union organizer in New York City; and Dean Spade, an associate professor of law at Seattle University and founder of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project.

Spade and Lacy spoke with UMSL Daily about the focus of the campus event, which is free and open to the public.

As a legal scholar, Professor Spade, in what ways have the “limits of law,” to steal a phrase from your book’s subtitle, captured your attention?

DS: The reason I became a lawyer was because I was an activist in movements seeking to end poverty, racism, prisons, gender violence and other harms that permeate our society and our legal systems. I went into law hoping that I could gain skills to help stop people from getting evicted, deported and imprisoned and be part of changing unfair systems that keep people poor, homeless and in danger.

What I have learned from being a lawyer and a law scholar is that the oversimplified idea that we can end the harms and violence we see by changing laws through courts, legislatures and elected officials is actually a big obstacle to change. We are raised to believe that legal change is the key way to make change, and we are told stories about how the U.S. was redeemed from systems of slavery, Jim Crow segregation, sexism, racist immigration quotas and the like by legal changes that brought equality and fairness. Yet we live in a society that is deeply unequal and unfair, and often these systems were only changed on paper; meanwhile, racialized and gender maldistribution got sharper and more severe.

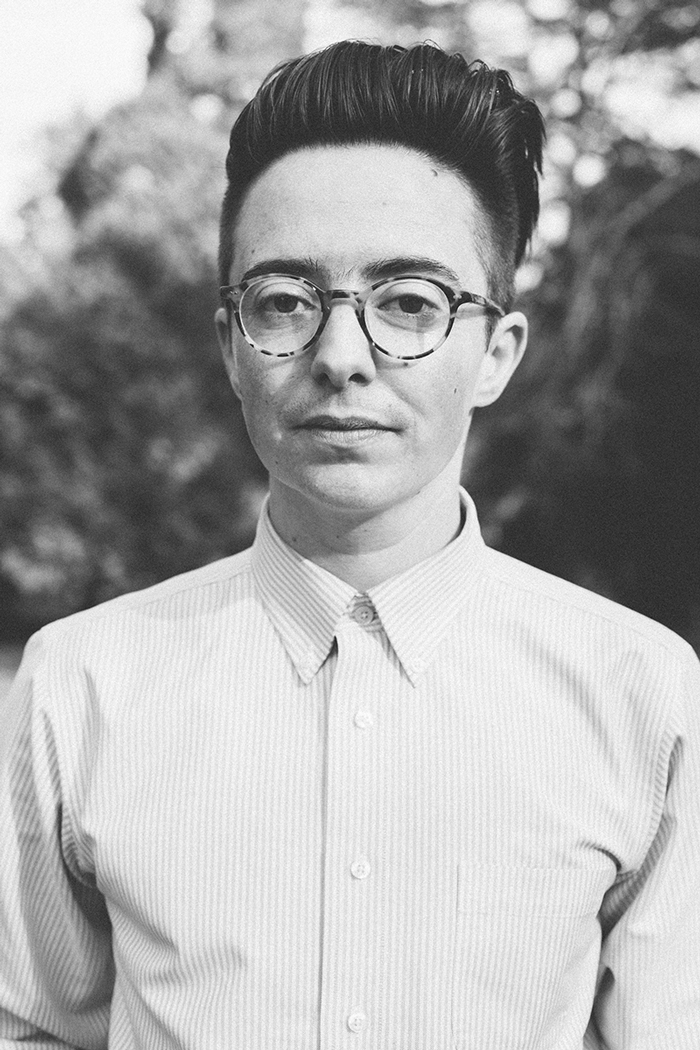

Dean Spade of the Seattle University School of Law is one of the panelists speaking at the event, titled “Beyond Reform: The Limits of Legislating Equality for Black & Brown and LGBTQ+ Liberation.” (Photo courtesy Dean Spade)

One theme in my work is looking at how certain legal reforms are misleading, and analyzing law reform strategies from an understanding that U.S. law was built on racism, colonization and capitalism and is not going to be the way to end those things. Given that, what legal work do we want to do, and how do we want to do it, so that we can bring as much immediate relief as possible to people suffering from the violence of these systems but also work to dismantle, rather than mend and strengthen, these systems?

On first glance, the upcoming panel’s pairing of topics might seem a bit surprising. How do you see them intersecting?

SL: Many communities suffer oppression in our society. Racism, sexism, homophobia, et cetera produce the same outcome: one group does not have access to the same opportunities as another based on identity, and in severe forms, one of those opportunities they are denied is life. The fights for racial equality and gender/sexual orientation equality have focused on different highlight issues, but they both are underpinned by major economic forces.

People of color and LGBTQ+ people are much more likely to live in poverty. Addressing economic inequality through campaigns for increased minimum wage, rent control or public benefits would raise living standards in both communities. Therefore we address multiple identities with our thesis about ways to achieve liberation outside legal reform.

That is one problem with focusing on issues such as marriage equality. Not only is that issue more relevant to the higher socioeconomic classes of the LGBTQ community, it also does not achieve social equality. How does a queer person living in poverty see their daily existence improve by the legalization of gay marriage? They don’t. Their liberation cannot be legislated into existence.

What do you think these various groups and movements can learn from each other?

SL: We can look at how we as activists, allies and members of marginalized communities effect change locally and nationally that will improve our lives and the lives of our brothers and sisters. In the last year, communities of color have literally taken to the streets in cities across the country to cry out that police execution is inexcusable. However, LGBTQ community members, especially trans women of color, are also being targeted, but the response has been more muted. The death of anyone at the hands of law enforcement should be questioned, and if answers are not forthcoming, local government should anticipate streets full of people.

But I actually think both activist communities have done a good job of studying the history of the other. Still, all movements also need to have more democratic debate within the communities they represent as opposed to pursuing the interests of a limited number of activists.

Professor Spade, in what ways have you observed legal reform and other activities working together toward social justice?

DS: In my Law and Social Movements class, we talk about this exact question. What role should lawyers and law reform have in movements? When have lawyers and legal strategies been successful in helping movements make big changes? One of my favorite readings about this is the 1975 book “Detroit, I Do Mind Dying,” written by Dan Georgakas and Mavin Surkin. It tracks the development of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in the 1960s and 1970s. At the time, activists in the black liberation movement in Detroit were trying to expose the awful conditions that black workers faced and the brutal treatment that black people experienced at the hands of the police, in addition to many other issues.

The book tells stories about how the lawyers in the movement were successful at putting whole systems on trial in cases where usually it would be almost impossible to win. It is inspiring to learn how – within the broader social movement context, and with the ways that the black liberation movement was changing what people across Detroit (and the world!) thought about their lives and what was possible – radical things could happen even in courtrooms.

Unfortunately, these days many legal organizations are very separate from grassroots community organizing groups. Also, many lawyers who provide legal services to poor people are prevented by funding restrictions from engaging in tactics that would mobilize collective action rather than only addressing cases individually in proceedings in which the deck is stacked against the poor person. There is a lot of work to be done to radicalize legal service provision and poverty lawyering and help de-professionalize it and bridge it to social movements.

What do you make of the last year or so when it comes to remaining challenges and oppression in our world, across the U.S. and in our own communities? Where do we go from here?

DS: The last year has been a powerful time to witness the brilliant resistance of black communities to the ongoing pervasive violence they face. I am awed by the ways that grassroots work in local communities across the country has shifted public perception of policing and anti-black violence and brought new attention to the outrageous conditions of mass imprisonment and militarized racist policing that have become normalized across the U.S.

It has also been a time of important conversations about the specific ways that anti-black racism operates and the many roles in which people who want to support black resistance and black life can take responsibility and plug in to this resistance work. I am inspired by all the work people are doing, the risks that activists are willing to take and the generosity that people in different movements and organizations are showing each other.

SL: The last year has been both inspiring and devastating – devastating in that the true numbers of people in the United States being killed by law enforcement are finally coming to light, and it is shockingly high. But it’s inspiring to see that young people are not apathetic about it. Some search for electoral solutions, but many see protest and direct action as the best way to effect change. And the protestors are diverse in age, race, sexual/gender identity and class.

I think UMSL’s location near Ferguson is important. We are seeing the beginning of the next civil rights era with the Black Lives Matter movement, Dream Defenders, demands for greater visibility of the trans community and so forth. It is no accident that presidential candidates have been visiting Ferguson or sending delegates to conferences here. They too see these as seminal issues for the future of our country.

In helping to organize the panel, my aim is to support the movement for black and brown and LGBTQ equality in my own city. My students reflect this diversity. I stand with them, and I hope this shows them that higher education can be a powerful force for social and economic change.