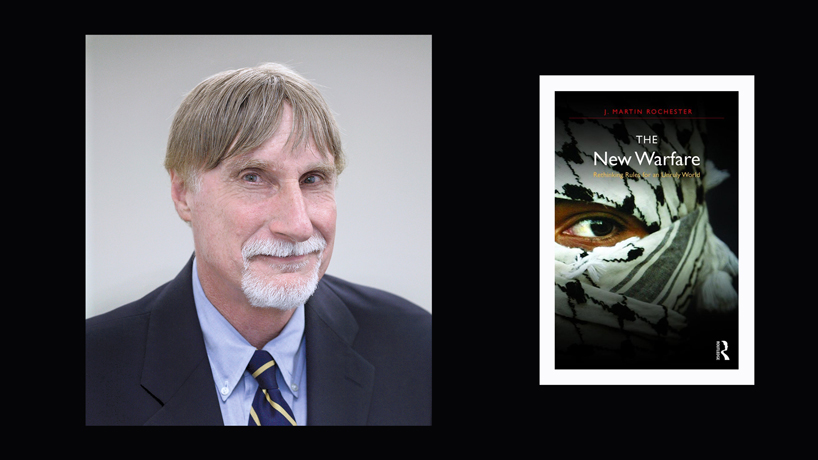

University of Missouri–St. Louis Curators’ Teaching Professor J. Martin Rochester has published 10 books spanning subjects such as international law, education and war. (Photo by August Jennewein)

J. Martin Rochester believes the 1945 United Nations Charter and the 1949 Geneva Conventions are outdated in this age of guerrillas, terrorism and drone strikes.

In his latest book, “The New Warfare: Rethinking Rules for an Unruly World,” Rochester offers a frank analysis of how today’s policymakers should update and adapt the laws of war in response to modern conflicts.

“For hundreds of years the main form of warfare that threatened the world was large-scale armed combat between organized national armies,” said the University of Missouri–St. Louis political science professor. “The wars occurring now are harder to manage, harder to terminate and feature very messy, very complicated combinations of interstate violence, intrastate violence and transnational terrorism.”

As Rochester explores difficult questions of how to fight honorably, he finds that outdated rules of engagement put the United States in a dangerous legal and political gray zone.

“Let’s say we have 99-percent-accurate intelligence that a terrorist cell in Yemen is going to blow up New York’s Lincoln Tunnel and the subway system, rendering the city uninhabitable. And if we know they’re about to do this, can we take a drone strike and eliminate them before they carry out this attack? Do we have the right to engage in the preemptive use of armed force? If we have reason to believe someone is going to attack the U.S., the [United Nations] charter says you can’t shoot first, but do we have the luxury of waiting until New York City is destroyed before we can attack?”

Rochester also considers how the general population may be targeted by a terrorist attack, anywhere, anytime.

“Another quandary is how can the United States be expected to comply with the ‘rule of distinction,’ meaning combatants should be targeted rather than civilians,” he said. “What do we do when our adversary often not only explicitly attacks innocents but hides behind them and places munitions in schools and hospitals?”

Political science senior and Student Veteran Association member James Norris knows that challenging scenarios like the above are at the heart of Rochester’s classroom discussions.

“Professor Rochester makes a point to discuss different perspectives and positions on controversial political issues,” said Norris. “He has made me aware of my own personal biases and helped me strengthen my position using facts. I avoid accepting what the media spits out and evaluate issues with the knowledge of what questions to ask and where to look.”

Beyond his research and lecturing at UMSL, Rochester also engages local K-12 schools and community organizations like the World Affairs Council of St. Louis on the importance of serious, wide-ranging inquiry.

“I want students to take away the notion that the world is an incredibly complex place and that they should cultivate their own view of what the world looks like based on the best available evidence,” he said. “The best definition of education I ever heard was that an educator should teach students to cope with ambiguity.”

Even though Rochester has published several political science books that are used in universities all over the world and has shown himself to be a prolific author, he is never sure what might attract his attention in the future.

When asked about the progress of his next book-length project, he said, “I’ve written ten books, and I have a few more ideas, but I hope I still have something worth saying.”