Professors (from left) Wendy Olivas, Erika Gibb and Cynthia Dupureur serve as the UMSL department chairs for biology, physics and astronomy, and chemistry and biochemistry, respectively. It’s the first time in the history of the university that all three science departments are led by women. (Photos by August Jennewein)

Role models. It’s a recurring theme in President Barack Obama’s 2013 report on “Women and Girls in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math.”

“Giving greater prominence to strong role models is not just the right thing to do, but the smart thing to do,” the report says of addressing the low percentage of women in STEM fields – just 24 percent in 2009.

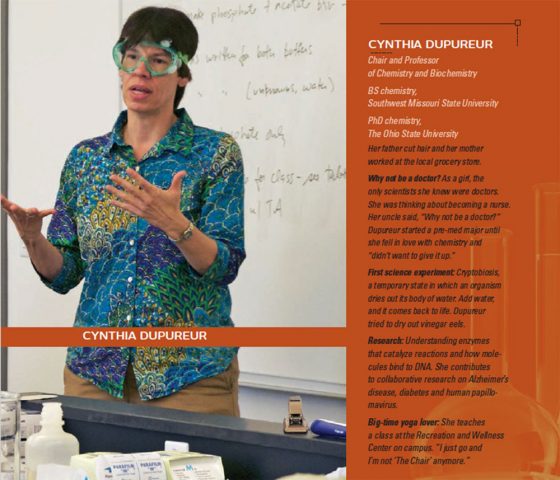

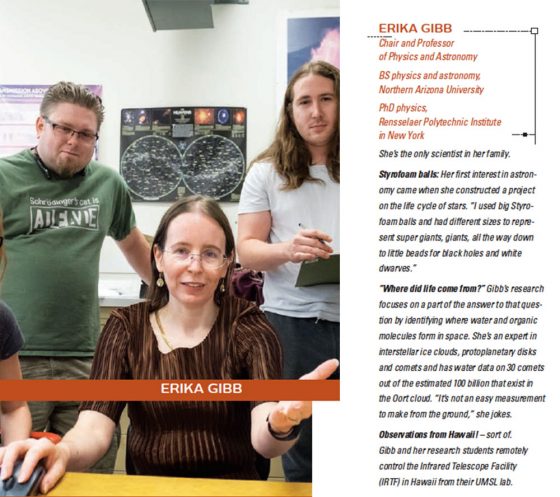

Faculty at the University of Missouri–St. Louis are leading by example. For the first time in the history of the university, all three science departments have women chairs – Cynthia Dupureur for chemistry and biochemistry, Erika Gibb for physics and astronomy, and Wendy Olivas for biology.

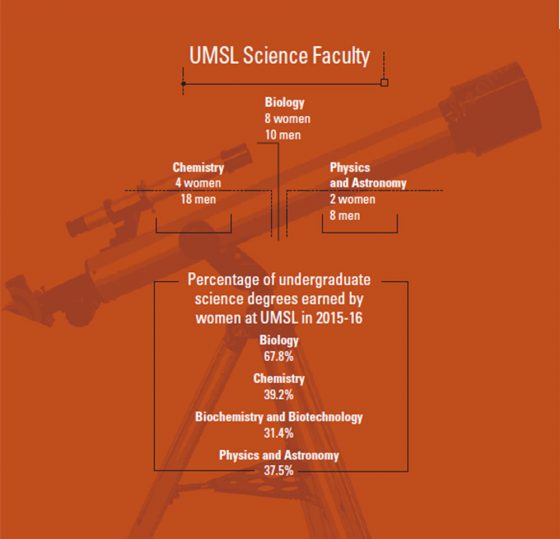

The odds of that happening aren’t high, according to the most recent research. The 2010 survey “A National Analysis of Diversity in Science and Engineering Faculties at Research Universities” by University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson presents startlingly low numbers of women STEM faculty nationally. The data from the top 100 research universities shows women made up only 13.7 percent of faculty in chemistry, 9.5 percent in physics, 15.8 percent in astronomy and 24.8 percent in biology. Many of those positions weren’t tenure-track either, greatly reducing the chance for promotion to chair.

“Having three women department chairs in our sciences is a milestone UMSL is proud to achieve,” Chancellor Tom George says. “Not only is it a testament to the university’s diversity across campus, but it points to the opportunities UMSL affords women who want to study, research and teach in STEM disciplines.”

For Olivas, UMSL’s welcoming environment for women played a large role in her choosing to accept a position in the biology department in 2000. She had other offers but declined when she sensed she might be the token female.

“I saw that there were many women faculty members here and that they were in leadership roles,” says Olivas, who noted that a woman, Blanche M. Touhill, was chancellor of UMSL at the time and that Des Lee Professor of Zoological Studies Patricia Parker has twice been biology chair. “We’ve had this record of women in leadership positions, so it’s been made easier to advance because it’s not odd to have women in these roles. Go around our colleges, and many deans and chairs are women.”

In fact, the three chairs don’t feel that being a woman had much, if anything at all, to do with their advancement.

“When it came time to fill the chemistry chair position, my colleagues asked, “‘Who can do the job?’” Dupureur says. “I don’t get the sense that they were really wrapped up in gender. It wasn’t important. The important stuff was how do we lead the department.”

A woman getting a job or raise based on skill and merit – not so shocking at UMSL. But more important for the three chairs is the influence they have on their students and the hope they represent for young women interested in STEM.

“I remember I was frequently the only girl in the advanced science and math classes in high school,” Gibb says. “After that, it just became the norm. We still lose a lot of girls at that middle-school age. They start dropping out of sciences because they seem to think they’re not good at it or that it’s hard. I think that’s very limiting. It’s important for girls to be interested in everything but especially important for them to be interested in science fields that, for whatever reason, they feel pushed out of.”

The Nelson Diversity Surveys show that national efforts to boost gender equality in STEM education are paying off. In 2005, women at the top 100 universities made up 51.7 percent of conferred bachelor’s degrees in chemistry, 42.4 percent in astronomy, 21.2 percent in physics and 62.2 percent in biology. So the education pipeline is full, but it doesn’t yet seem to translate into equal representation in faculty or field professionals.

Just how did Gibb and her fellow science chairs make it? They all give versions of the same answer – stubbornness to persist because of pure love and curiosity for the science. Gibb also notes that it takes awhile to see results from diversification efforts.

“Two of the last three tenure-track hires, including myself, were women in the department,” she says. “Everybody prior had been here 20 years already and fewer women were in science back then. I think it takes a little bit longer for the demographics to catch up when tenure-track faculty could easily be in their positions for 40 years” – just another reason to celebrate the three women who beat the odds and the departments who celebrate them as leaders and, of course, role models.

This story was originally published in the fall 2016 issue of UMSL Magazine. Have some praise and/or suggestions for UMSL Magazine? Please take the five-minute 2016 UMSL Magazine Survey.