Ashland Tate, BA 2008, was attending the University of New Orleans in the fall of 2005 when Hurricane Katrina prompted a major change of plans. With assistance from Boys Hope Girls Hope, Tate moved to St. Louis and enrolled at UMSL, where he was able to finish his semester at no cost. (Photos by August Jennewein)

Eleven and a half years ago, New Orleans native Ashland Tate had two options to choose between: Missouri and Nebraska.

“Nebraska just seemed like a whole other planet at that point,” recalls the self-described ragin’ Cajun, whose beloved hometown was suddenly under water and facing catastrophic devastation. “I thought, ‘Well, St. Louis – I can wrap my head around that. That’s not too far, and we’ve got a lot of things in common as far as urban areas.’”

Born and raised in the Lower Ninth Ward, the area hit hardest by Hurricane Katrina, Tate was a student at the University of New Orleans at the time. He was also a recent alumnus of Boys Hope Girls Hope New Orleans, a program that provides stability and academic opportunity for young people in need.

When the storm happened, shutting down much of the local infrastructure, the organization reached out to ask if he was interested in finishing out his college semester somewhere else.

“They’d already put some feelers out to see which schools were receptive – and a lot of schools were – but those were the choices that stood out to them, for one reason or another,” Tate says. “So I tried out St. Louis, and when I got off the airplane, we drove straight to campus.”

He arrived to a warm welcome at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, which covered his tuition that fall. And while he’d expected his time at UMSL to be relatively short, Tate ended up staying on at the university all the way to graduation.

He remembers immediately feeling right at home thanks to other students in his residence hall, a fraternity he soon joined and many other student organizations as well.

“Initially the goal was to go back to New Orleans, but we had no idea how bad the devastation was, and going back wasn’t going to happen as soon as we thought,” Tate says. “And throughout that time at UMSL, I was making new friends, I was getting comfortable in my classes and I didn’t feel alone.

Ashland Tate (center), the new executive director of Boys Hope Girls Hope St. Louis, stands surrounded by colleagues (from left) Cherae Bullard, Cassandra Sissom, Rachel Bene, Sara Holmes, Jan Wacker, Terrance Lockett, Caitlin Bone and Julie Newman.

“So I just continued to stay. And I’m still here [in St. Louis] – three months turned into 11 years.”

Along with earning his degree in communication and media studies in 2008, Tate became heavily involved with the then-fledgling UMSL Radio efforts, which often kept him and fellow DJs up late into the night.

He says it was all worth it and a highlight of his student experience, despite the frequent lack of sleep.

“At that time it had just started inside Dr. [Charles] Granger’s biology office,” Tate says. “There were jars of frogs and all kinds of stuff that you never would normally see in a radio station. And it started to really get off the ground, and people around campus were getting interested in having radio shows and streaming online.”

With its booth now centrally located in the buzzing Millennium Student Center, UMSL Radio, also known as the U, continues to generate student interest and involvement.

“I was there when we cut the ribbon for that,” Tate says of the MSC space, “and I think I was the third radio station manager we had there.”

Radio wasn’t his only interest. Tate also met his wife while at UMSL. A national exchange student from Idaho, she eventually returned to Boise State University to finish up her own degree.

But their paths soon intersected again in St. Louis, where their connection to their adopted home has grown even deeper, along with Tate’s connection to an organization that has helped him find his way since age 13: Boys Hope Girls Hope.

“I lived with my mom and my two younger sisters when I was younger,” Tate explains. “My mom suffered from bipolar schizophrenia, and her mental illness really prevented her from doing a lot of the basic things she needed to do as far as raising us. She struggled with taking her medications, she struggled a lot with relationships, and there were some really tough times there that really made it difficult for me and my sisters to be in the home.”

One of his biggest fears, as early as age 9, was that he and his sisters would get taken away and “lost somewhere in the system,” Tate adds. He tried to help out around the house however he could. But the situation grew increasingly unstable for the siblings, and eventually a counselor at Tate’s middle school referred him to Boys Hope Girls Hope.

“I went through the application process, and when I went to the home, I really wanted to stay,” he recalls. “I saw all the kids there, and I could hang up pictures and posters on my wall. It was nice. We had sit-down dinners at the table every night, we had reflection in the evening, we got rides back and forth to school and we could get together with friends on the weekend. I hadn’t had the opportunity to engage in a lot of the things that a lot of other kids got to do.”

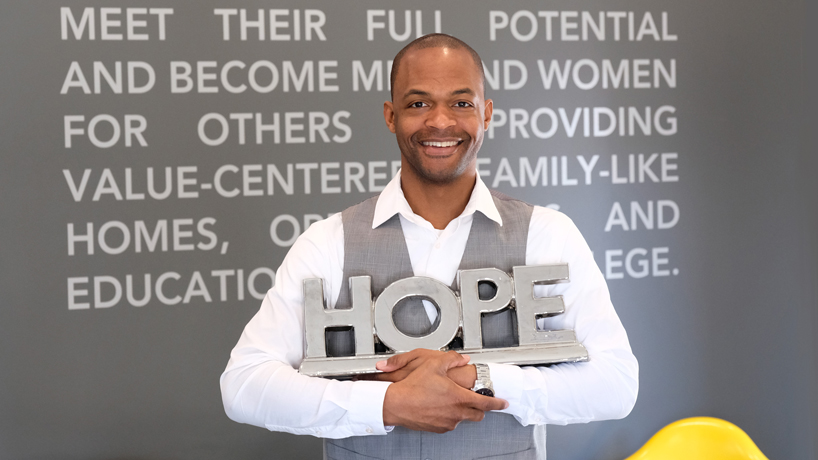

“When you walk into our doors here in St. Louis, our mission statement is on the wall, and every part of that mission has been ingrained in me since I was 13, and I believe every single part of it,” says UMSL alumnus Ashland Tate.

When the New Orleans chapter opened up its first girls’ home during Tate’s high school years, his two younger sisters were among the first to be admitted. His own ties to the nonprofit have outlasted his graduation so many years ago and his move to St. Louis.

He’s continued to contribute as a volunteer in the decade since – and even started an alumni association that helps graduates of the program’s 18 chapters across the country continue to network and find support.

“When I think of the things Boys Hope Girls Hope did for my sisters and my mom, how could I not give back?” says Tate, who is now raising two sons of his own. “And having Katrina happen and coming up here and having them still extend out their hand to help me restart again – it was automatic.”

In December, Tate began a new appointment as executive director of Boys Hope Girls Hope St. Louis. He’s the first graduate of the program, nationwide, to come back and lead a chapter. And it happens to be the original chapter, too.

“Boys Hope Girls Hope started here in St. Louis,” Tate says. “This was the first affiliate in 1977, and this is also where the international office is based. I’m looking forward to having our affiliate and the [alumni] network be a shining example, a model affiliate, for others.

“I thank God every day, and I also pray for strength and leadership and guidance to make sure we make the right choices and decisions for the kids that are entrusted to us. I’m in the seat now to help make them, and I’m excited about the future.”