Chancellor Tom George (at right) and UMSL’s Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center Interim Director Patty Parker (at left) present entomologist May Berenbaum her award after Berenbaum gave the 2017 Jane and Whitney Harris Lecture at the Missouri Botanical Garden. (Photos by Marisol Ramirez)

An entomologist with a sense of humor? Of course the two aren’t mutually exclusive, but encountering the combo goes against many people’s stereotype of those who devote their lives to the critters society generally despises.

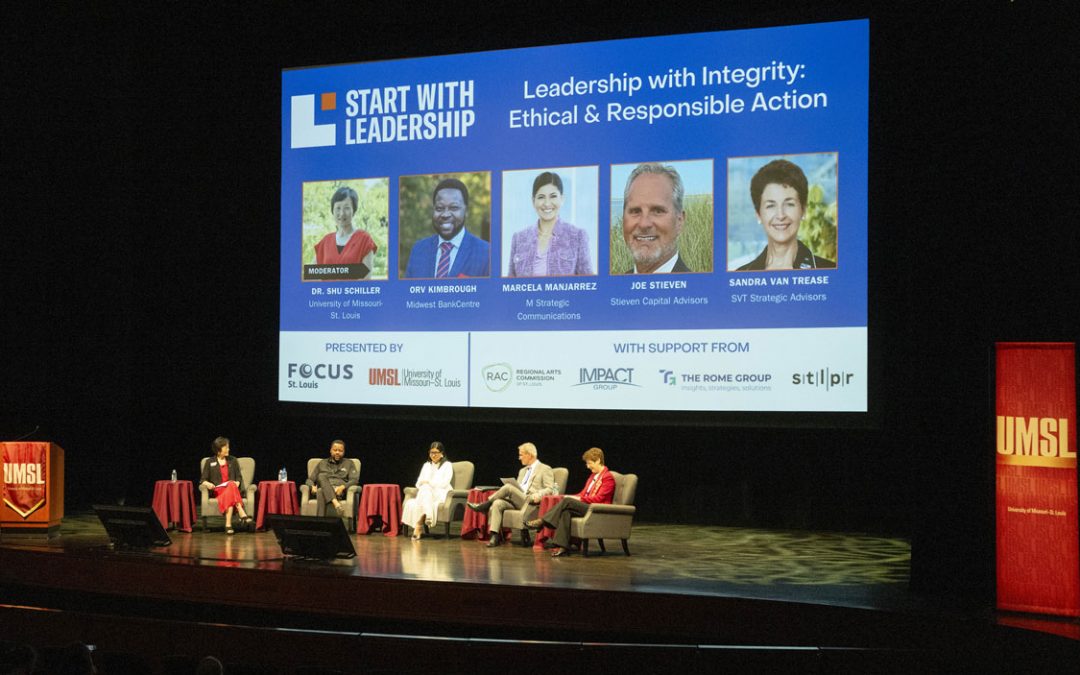

However, May Berenbaum, a professor and head of entomology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, had it all – the facts, the research and the humor – in her 2017 Jane and Whitney Harris Lecture at the Missouri Botanical Garden Thursday night. Nearly 150 were in attendance.

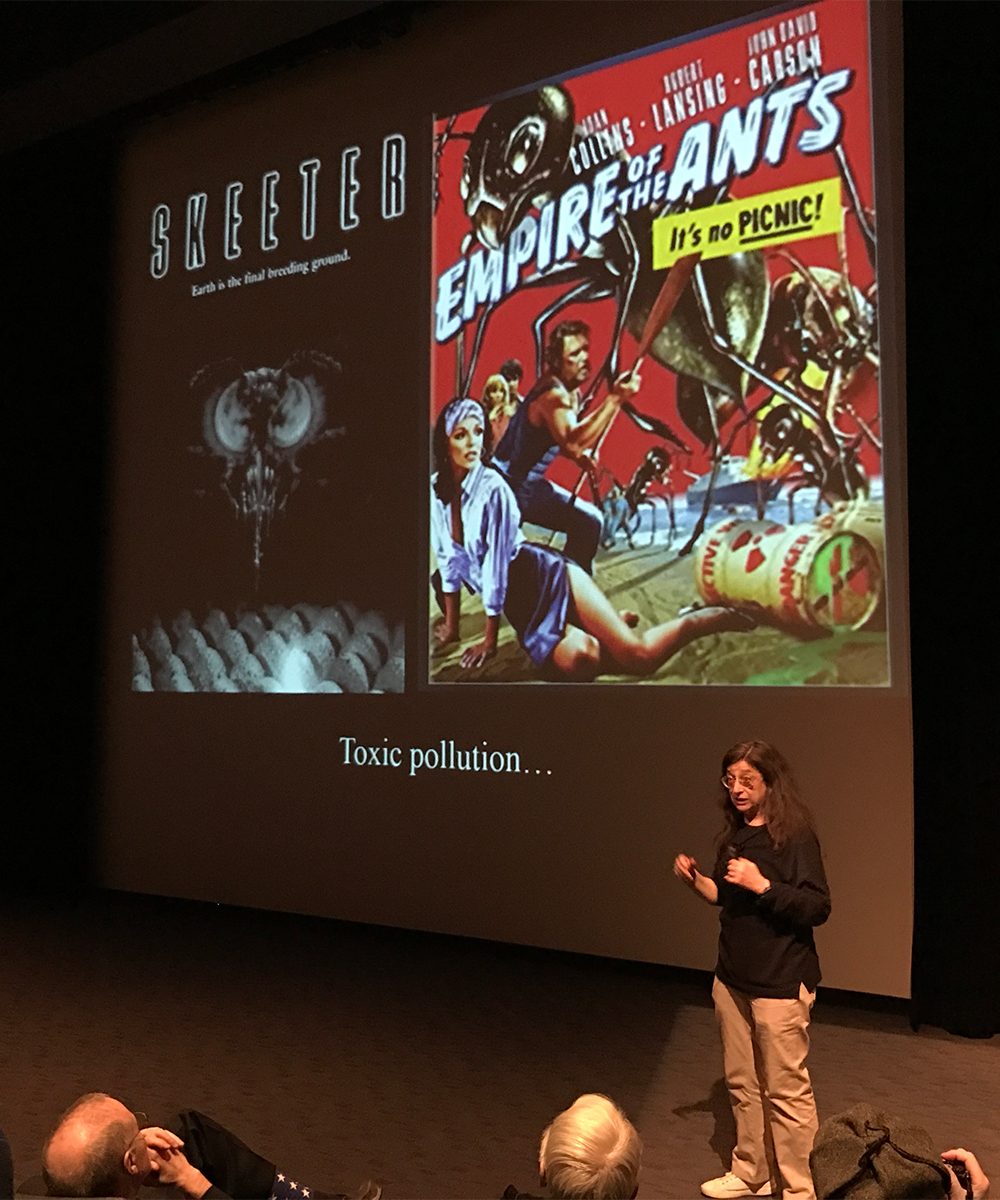

“Skeeter” and “Empire of the Ants” were two of more than a dozen environmental disaster films with which May Berenbaum opened her lecture. Both flicks are about giant mutant insects taking over, but Berenbaum said the inverse story, where humans drive insect extinction, is not so commonly depicted in Hollywood.

Organized by the Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, this year’s lecture was titled “Human Impacts on Insect Affairs.”

One might think Berenbaum would start with the standard images of bugs, but instead she opened with a series of movie posters showing Hollywood’s fascination with environmental disaster, including those caused by pests.

“Here’s a classic,” Berenbaum said. “‘Skeeter,’ where toxic mine waste led to the appearance of mutant giant, blood-thirsting mosquitoes. And then there’s ‘Empire of the Ants’ with toxic radioactive waste dumped on Florida swampland that gave rise to giant mutant ants.”

In the movie, the ants enslave local inhabitants using pheromones and force them to run the local sugar factory.

There were plenty of laughs but also plenty of facts as Berenbaum dug into the real world problems insects face that aren’t depicted in the movies, including extinction. Research citation after citation, she left no room to question that the rate of insect extinction is growing, and much too fast.

“This is due to anthropogenic extinctions,” Berenbaum said. “Extinctions of plants and animals aren’t caused by outside forces like asteroids in Bruce Willis movies but instead by humans.”

Her next fact: Without insects, the world just wouldn’t be the same.

While no insects certainly sounds appealing to some, the consequences of insect extinctions often don’t. Berenbaum used the beloved McDonald’s Big Mac hamburger meal to get at the point.

“One pollinator species alone contributes to 90-plus crops,” she said. “Without them, we’d have no patties, no cheese, no lettuce, no onion, no pickle – we’d have the bun, but no sesame seeds – no milkshake and no chocolate.”

Two-thirds to three-fourths of all flowering plants depend on pollination. There are about 200,000 species of insect pollinators compared to the 12,000 vertebrate pollinators.

And pollinators account for only a fraction of the insects in existence. Pollination itself is only one way insects contribute. They also act as natural control for other species, break down decomposing bodies, eat manure and serve as nutrition to animals.

But insects, Berenbaum said, don’t get nearly as much love as humans’ fellow vertebrates, especially mammals. Comparatively few insects earn the “at risk” distinction often given to mammals.

“No tears shed for the yorba linda weevil,” teased Berenbaum, who said that 61 percent of the critically endangered insects don’t even have a common name compared to the 1.6 percent of critically endangered mammals without a common name.

She also noted that the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which manages the endangered species list, includes insects, but almost all are butterflies. The first bumblebee species made the list this week, but only after President Donald Trump reversed his previous decision to freeze the rusty patched bumblebee’s listing.

Outside of naming and pushing for protective status, Berenbaum insisted that people take their cues from Hollywood and tell more insect stories, though perhaps ones that educate society about all the ways insects indirectly help create and maintain the world in which people live.

From the well-known stories like the monarch butterfly’s journey to Mexico to the lesser-known stories about dragonflies that inspire wind turbine technology or the beetle crucial to the fungus in a medicine that helps people to not reject kidney transplants – these stories help demonstrate the complex ecosystem humans rely on and insects contribute to at every turn.

“If they aren’t surviving,” Berenbaum said, “that’s an important reason and sign for us that if we keep living how we’re living, we may not survive too.”

Through events like the Harris Lecture, the Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center at UMSL aims to raise awareness of the need for biodiversity conservation. The center partners with the university, the Missouri Botanical Garden and Saint Louis Zoo to support awareness efforts as well as education and research ecology. The lecture is sponsored by the partnership.