Jacqueline Patterson (third from left), the director of the NAACP’s Environmental and Climate Justice Program, responds to a question from the audience during the 2017 Whitney and Anna Harris Conservation Forum Thursday evening at the Saint Louis Zoo. Joining Patterson during the panel discussion were fellow presenters (from left) Pandora Thomas, Sacoby Wilson and Carole Gibbs. (Photos by Steve Walentik)

Meghann Humphries remembers first being introduced to the idea of environmental justice during her time as an undergraduate over a decade ago.

“I remember something about a correlation between median income in a community and superfund sites or hazardous waste sites,” said Humphries, who now is in her fourth year working toward a PhD in biology at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. “But I never really pursued it to kind of figure out what does that really mean for these communities that are affected and why certain communities are affected.”

She gained a much deeper understanding of the subject by attending the 2017 Whitney and Anna Harris Conservation Forum last Thursday inside The Living World at the Saint Louis Zoo.

Humphries was one of about 300 people from UMSL and the broader community – among them a group of students from Jennings High School – who packed into the Anheuser-Busch Theatre for the annual event. It’s been put on by the Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center every year since 1997.

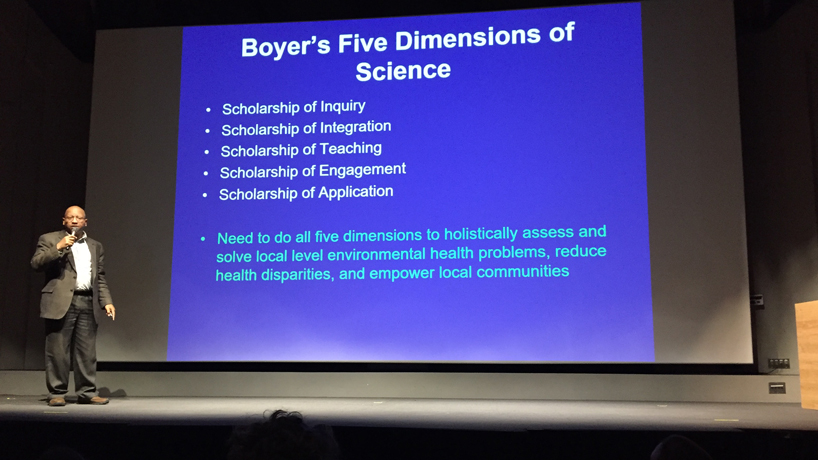

Sacoby Wilson, an associate professor in the School of Public Health at University of Maryland-College Park, discusses the need to take a holistic approach to assess and solve local environmental health problems.

The night featured presentations from ecological designer Pandora Thomas, University of Maryland–College Park public health Professor Sacoby Wilson, Michigan State criminology Professor Carole Gibbs and Jacqueline Patterson, director of the NAACP’s Environmental and Climate Justice Program, each adding a different perspective to the discussion of environmental justice.

Patty Parker, the E. Desmond Lee Endowed Professor in Zoological Studies who is currently serving as the interim director of the Harris Center, was responsible for making that the focus of this year’s forum. She explained the subject’s importance during her opening remarks.

“We understand when we’re working in developing nations that the people there need to own the problem for the conservation efforts to be successful, and we can’t expect them to care about it until their own basic needs have been met,” Parker told the audience. “Somehow we miss that same argument here in our own country, where we have marginalized communities that are disproportionately impacted.

“If we indeed want to do the best job of conserving biodiversity and the environment in our country and elsewhere, we need everyone to care. And we can’t expect everyone to care until we remove these disparities that make basic life much more challenging for some groups than others.”

The Environmental Protection Agency defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

In his presentation, Wilson explained why that definition falls short.

“We know that we want to make sure everybody is protected, but we know that everybody is not,” he said. “All people are not protected. We know people of color are overburdened. We know poor folks are overburdened. We know marginalized folks are overburdened.”

Carole Gibbs, an associate professor at Michigan State University with a joint appointment in the School of Criminal Justice and the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, talks to the audience about the environmental impact of corporate crime.

He went on to define another term coined by African American civil rights leader Benjamin Chavis: environmental racism. That is, as Wilson said, “the intentional or unintentional racial discrimination in the enforcement of environmental rules and regulations, the intentional or unintentional targeting of minority communities for the siting of polluting industries, differential enforcement of environmental laws and statutes, and exclusion from public and private boards, commissions and regulatory bodies.”

It can show up dramatically in cases such as the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, but also in seemingly more mundane policy decisions such as where to locate a chemical plant. Wilson noted that once a chemical plant or hazardous waste site is located in a particular community, that community is more likely to see a second or third constructed nearby.

Disadvantaged communities also find it more challenging to fight corporate criminals – which is Gibbs’ primary area of research.

“Part of what you’ll hear in my work tonight is finding all of the ways that it’s so very easy for businesses and corporations to harm not only the environment but also to have disproportionate impacts on marginalized communities,” she said.

She talked about white-collar crime, which she described as “using specialized techniques of deception or fraud to engage in criminal activity and how that harms the environment in certain communities in particular.”

One topic she discussed was the negative environmental impact created by electronic waste worldwide, with developed countries such as the United States often exporting their waste – and the potentially hazardous material contained in it – to developing nations.

Pandora Thomas, an ecological designer, speaks about the concept of Sankofa, a word from the Twi language of Ghana that emphasizes the importance of learning from the past. It fits neatly with the tenets of permaculture.

But the event offered a brighter side to combat the bleak.

Thomas discussed permaculture and how its principles are useful not only in creating fruitful landscapes but also healthy and productive people and communities.

Gibbs shared some things individuals can do to lower the impact of electronic waste – things as simple as refraining from trading in their iPhones every time Apple releases another model.

Wilson stressed how the work for change at the community level is most effective when it is done alongside the people who live there and not simply on their behalf.

Patterson delivered a wide-ranging presentation about people pushing for systemic changes. In it, she spotlighted an example of organizing in action as a group of citizens in Highland Park, Michigan, got together to bring solar-powered streetlights to their low-income neighborhood, which wasn’t being served by the local power company.

“It was nice to hear, not just that, ‘Hey, there’s this problem,’ but to also work toward solutions,” Humphries said. “I noticed that about all of the speakers, that they were all talking about how we can remedy this, how we can go forward.”