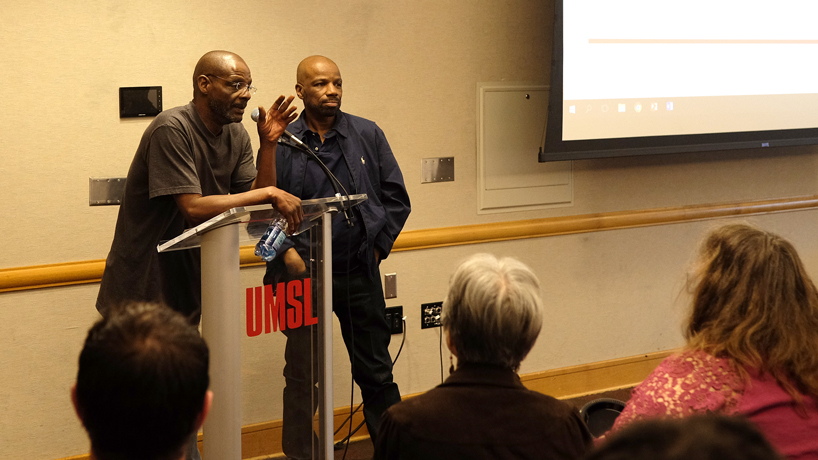

Joseph Amrine (left) addresses a question from the audience as Reggie Griffin looks at during a conservation titled “Two Death Row Exonerees: Death is Not Justice” Friday at the Millennium Student Center. (Photos by Steve Walentik)

Reggie Griffin had his audience captivated as he told them about all the moments of hope followed by disappointment and ultimately desperation that spanned his roughly 23-year fight to get off Missouri’s death row for a crime he didn’t commit.

With each appeal he imagined regaining the freedom he had lost, but they were all met with denials from the courts until he finally seemed out of options.

“I’m disgusted, depressed, angry because you feel like, ‘Hey, what do I have to do to show these people they got the wrong man?’” Griffin said. “None of it was working.”

He added: “You just get tired.”

Griffin was telling his story last Friday afternoon in the Millennium Student Center on the University of Missouri–St. Louis campus for a conservation titled: “Two Death Row Exonerees: Death is Not Justice.”

Former death row Joseph Amrine also took part in the discussion.

The Departments of Philosophy, Criminology and Criminal Justice and Political Science, the Gender Studies Program and the School of Social Work and the Student Social Work Association, the combined to sponsor the event. They did so in partnership with Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, a nonprofit organization dedicated to ending the use of the death penalty in the state of Missouri.

“UMSL’s mission statement is ‘We transform lives,’” Jill Delston, an assistant teaching professor of philosophy, said as she welcomed the near capacity crowd to Century Room A. “I think you’ll very soon understand how this event is to furthering that mission.”

Organizers were still bringing in extra chairs as the event got underway.

Reggie Griffin shares details of his roughly 23-year fight to escape death row for a crime he didn’t commit with a near capacity crowd in Century Room A at the Millennium Student Center.

Griffin began his nearly 40-minute talk by taking the audience through the details of his case.

He’d been imprisoned on an assault charge stemming from a street fight in his hometown of St. Louis when he had been wrongly convicted of first-degree murder in the 1980s.

His conviction came in 1988, but it was for the stabbing death of a fellow inmate at the Moberly Correctional Center five years earlier.

The word of two jailhouse informants helped convince the jury of his guilt. Both had received reduced sentences to testify against him, and he jury deliberated only 45 minutes before reaching its verdict.

Griffin’s two co-defendants had both consistently said that the third person involved in the crime had been inmate Jeffrey Smith, and prosecutors had withheld critical evidence that Moberly guards had confiscated a sharpened screwdriver from Smith immediately after the stabbing.

That information didn’t come out until years later, and it wasn’t until 2011 that attorney Ken Gipson successfully argued for the Missouri Supreme Court to overturn Smith’s death sentence.

It would be another two years – as prosecutors with assistance from the state attorney general unsuccessfully worked to reinstate his conviction – that Griffin was finally free. He was the fourth person exonerated from death row in the state of Missouri and, as of 2017, one of 158 men exonerated nationwide.

“Don’t get me wrong, I’m happy to be free, to have my life back,” Griffin said. “But even though I’m free, I still lost, y’all.”

Amrine, a Kansas City native, next took his turn behind the lectern, but he didn’t begin with his personal story. Rather, he offered sobering facts about the death penalty, including the uneven way it’s applied along racial lines.

“In 1986, they had a survey that showed that if you killed a black person, you stood less a possibility of going on death row than killing a white person,” Amrine said. “There was a thing that said if you were a black person, you probably would have an all-white jury and you were more likely to get convicted. There was another one that said that states that had the death penalty, their murder rate was higher than states that don’t have the death penalty.”

Amrine said those facts have remained unchanged since the 1986 – the year he was sentenced to death for the 1985 murder of fellow prison inmate Gary Barber. His conviction was won largely because of the testimony of fellow inmates, three of whom later recanted their testimony and admitted to lying in exchange for protection.

He noted that 114 people spent time on death row during his 17 years there before his own conviction was overturned in 2003.

Of those, four were exonerated while 64 men were executed.

“If we were cars, out of every 114 cars that we have coming off the assembly line, four would have a defect,” Amrine said. “If that was true, they would recall every last one of them cars – 600,000 cars would be recalled.

“We’re dealing with lives. They ain’t recalled nobody.”

The words of Griffin and Armine seemed to leave an imprint on those in attendance.

“I think that it’s exceptional that you all are coming out and letting everyone know the truth,” said one woman during a question and answer period. “I think this is the greatest way to overcome the whole system and the things that you have went through. I appreciate you, I thank you, and I think you all should continue to do just what you’re doing – speaking to crowds and letting them know what’s going on because I had no idea that the system was broken in this particular way.”