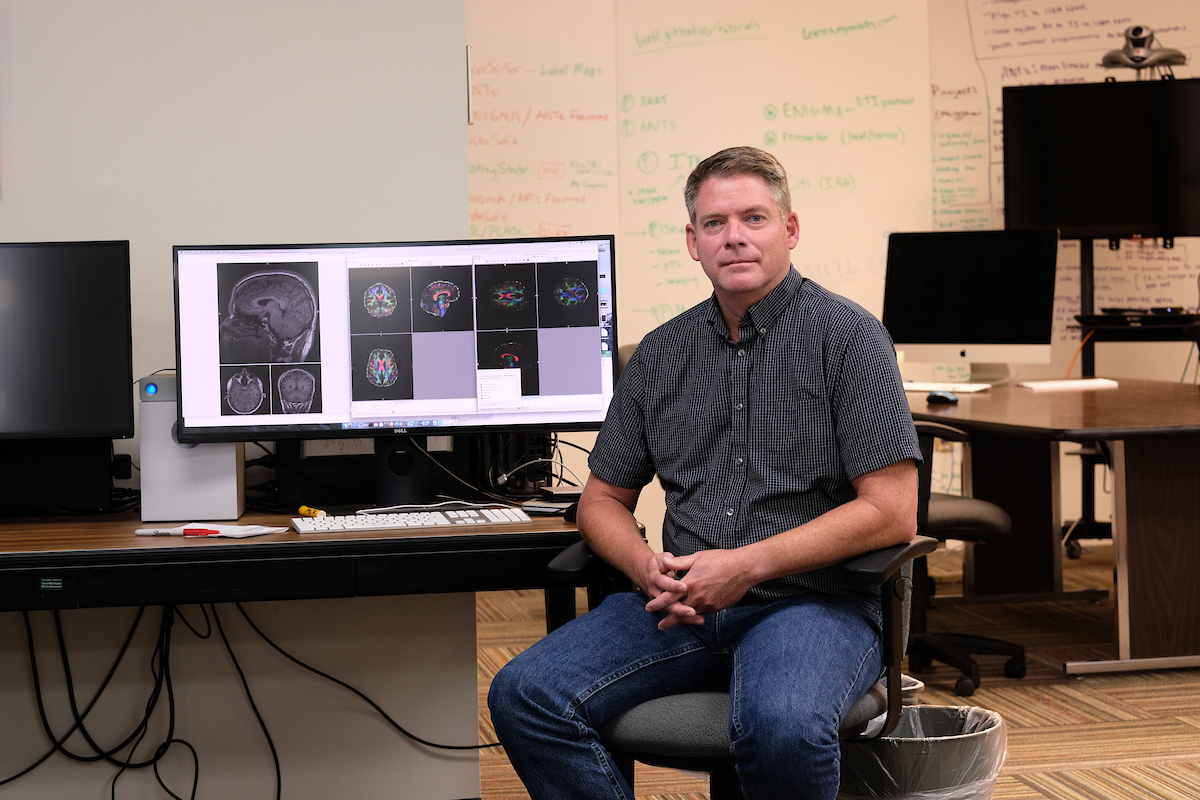

David Tate, an associate research professor at the Missouri Institute of Mental Health, uses diffusion-weighted MRI to study the behavioral effects of traumatic brain injury. (Photos by August Jennewein)

At first glance, they look like abstract paintings with their vibrant colors running and twisting in all directions on the wall across from David Tate’s office.

But the images aren’t modern art. They’re modern science.

They are computer-generated close-ups, created with diffusion-weighted MRI, that represent the flow of water through the brain.

Tate, an associate research professor at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, uses the technology as a central part of his research while directing the Brain Imaging and Behavior Laboratory at the Missouri Institute of Mental Health.

“We actually quantify different aspects of the brain, including just straightforward volumetric type of information – this is how big your brain is, this is how big your ventricles are, this is how big your thalamus is,” Tate said recently while sitting in his office at Innovative Technology Enterprises at UMSL. “We try to see if that relates to some of the behavioral symptoms that we see in patients across a number of different disorders.”

In 2017, he served as primary investigator for three Department of Defense-related grants totaling $793,320 to study such topics as the epidemiology of traumatic brain injury and epilepsy, the impact of high-altitude flying on the brains of U-2 pilots and the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation therapies.

The UMSL Office of Research Administration honored Tate in May as the Senior Faculty Investigator of the Year at its 2018 Research & Innovation Reception in the Millennium Student Center.

“It was nice to be recognized in that way,” Tate said. “It’s something I like to do, so I don’t know that an award is needed, but it is nice validation.”

Tate only came to UMSL in 2015, but he’s been studying the brain and brain injuries for nearly two decades, going back to his years spent pursuing a PhD in clinical psychology with an emphasis in neuropsychology from Brigham Young University.

He’s published work in leading journals such as “NeuroImage,” “Neuropsychology” and “Brain Imaging and Behavior.”

In the past year, David Tate, the Senior Faculty Investigator of the Year, has been the primary investigator for three grants totaling $793,320.

During his years of research, he’s seen plenty of advances with implementation and improvements in computer technology.

He recalled sitting in a dark room in his early days as a researcher, tracing brain specimens manually so that he could observe differences.

“Now we give it to a computer program and wait a few hours, and we have everything that used to take me months and even years to do,” Tate said. “So sort of the basic premise hasn’t changed that much. After an injury, the brain changes. We want to quantify those changes and then see if that doesn’t help us predict their functional outcomes or help us plan treatments.

“That hasn’t changed. But the methods evolve, and they evolve rapidly.”

Research on brain trauma has been a subject that’s generated plenty of interest outside the research community over the past decade, particularly in the context of concussions in the NFL.

Tate, coincidentally, started on the path to his present career after a football-related injury, though it was hurting his knee – not a blow to the head – as an undergraduate at BYU that helped him discover it.

He was just beginning to ponder what his future might be when he registered for a research design course taught by noted neuropsychologist Erin Bigler, who would become his mentor.

Bigler had been conducting research into Alzheimer’s disease and other developmental disorders and traumatic brain injury, and Tate found himself curious about both because he had a grandfather diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and had experienced several concussions while playing football.

His interest piqued, Tate soon found himself hooked on neuropsychology.

After completing his undergraduate and doctoral degrees at BYU, Tate did an internship and postdoctoral fellowship at Brown University in Rhode Island.

It was at Brown that Tate first met Robert Paul, now the director of MIMH, who was completing his own fellowship.

Paul would play a role in bringing Tate to UMSL, but Tate made several other stops first. After completing his training, he remained at Brown as an assistant research professor, then moved to Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, where he also served stints on the faculty at Boston Medical Center and Harvard Medical School.

In 2011, the Department of Defense was ramping up its research efforts into traumatic brain injury at a time when more and more troops were returning home from overseas conflicts. The department had a vested interest in understanding ways to treat the now nearly 380,000 service members diagnosed with traumatic brain injuries – mild or otherwise – since 2000.

David Tate’s colleagues from the Missouri Institute of Mental Health turned out to support him when he received the Senior Investigator of the Year Award at the Research & Innovation reception in May.

That created an opportunity for Tate to leave the Northeast, and he accepted a position as a research neuropsychologist at the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center in San Antonio, Texas.

After four years working as a researcher there, he decided he wanted to return to academia, and Paul offered him a new home at UMSL. It’s provided him a little more freedom to choose the projects on which he works.

“At this point in my career, I can pursue the things that are interesting to me and, therefore, that I tend to work a little bit harder on,” he said. “I’ve enjoyed being here, being more independent and in control of my own destiny.”

At the same time, UMSL has been a good base. He’s leading a research team of six people, including people with backgrounds in computer science, behavioral neuroscience, MRI physics, neurology and physical medicine rehabilitation.

He’s also found opportunities to collaborate.

Tate is just beginning work on a Veterans Affairs-funded grant to explore the interactions of traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder in cases of domestic violence. He’ll be working with fellow MIMH faculty member Kim Werner and other colleagues with the Center for Trauma Recovery on campus.

“I feel like I’m a good collaborator, and I think that’s probably why I’ve been as successful as I’ve been,” Tate said. “I recognize that I’m not the sharpest tool in the shed and that in order to do this and do it well, you really need expertise across a number of different disciplines coming together to address these kinds of questions. I’m pretty determined, too, and I think that goes a long way.”