Last week, the Graduate Women in Science hosted a viewing of Professor Meg Urry’s talk, “Women in Science – Why So Few?” The viewing was followed by a discussion about the talk and bias in STEM fields. (Photos by Burk Krohe)

When scientists are presented with a problem, their natural reaction is to dig into the data and study it.

That’s how Meg Urry, Israel Munson professor of physics and astronomy at Yale University, came to investigate gender bias in STEM fields. In 2011, Urry presented her work in a talk titled, “Women in Science – Why So Few?”

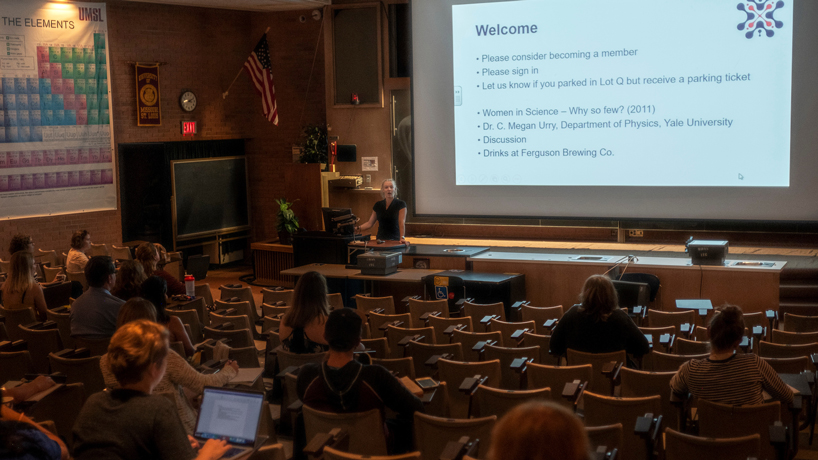

Last Monday, the St. Louis chapter of Graduate Women in Science hosted a viewing of her talk followed by a discussion at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. It was attended by students from UMSL and other local universities. Sandra Langeslag, assistant professor of behavioral neuroscience at UMSL and GWIS member, coordinated the event.

Langeslag attended Urry’s presentation in 2011 and thought she effectively addressed the gender biases that persist in fields such as computer science, engineering and mathematics.

“I really love the presentation,” Langeslag said. “I think she really explains very clearly what the problem is and what potential solutions are to increase diversity in STEM fields. I really wanted to share this presentation with as many people as possible, and Graduate Woman in Science is the perfect platform to do that.”

Assistant Professor Sandra Langeslag addresses attendees at the viewing. (Photos by Burk Krohe)

Urry started her talk by recounting early experiences in her career. At the time, she didn’t think there was any discrimination in the sciences.

“It took me a long time to figure out that what I was seeing was a kind of subtle discrimination,” Urry said. “The light bulb went off for me in the early ’90s when I started reading social science literature. It turns out that we scientists are a species of great interest to them, and they understand very well why there are so few women.”

Urry included statistics illustrating the disparities in the presentation. Eight years later, there is some improvement. However, data from the National Science Foundation’s benchmark reports tells largely the same story:

- Women received 59 percent of bachelor’s degrees in biological and agricultural sciences and 77 percent of bachelor’s degrees in psychology in 2015 but only 20 percent of bachelor’s degrees in engineering, 18 percent in computer science and 43 percent in mathematics and statistics.

- From 2000 to 2015, the share of women receiving bachelor’s degrees in computer science dropped from 28 percent to 18 percent.

- Minority women received 13 percent of bachelor’s degrees, 8 percent of master’s degrees and 5 percent of doctoral degrees in science and engineering in 2015.

- Women only account for 28 percent of the science and engineering workforce despite making up about half of the U.S. college-educated workforce.

Urry doesn’t believe the discrimination is intentional, rather it’s unconscious bias. She subscribes to the theory of “gender schemas.”

Gender schemas are expectations of others people develop unconsciously based on their own experiences. Urry noted they are natural and something all people do – not just men. They’re not necessarily malicious but can lead to stereotyping instead of objective assessments.

“Gender schemas aren’t wrong,” Urry said. “It’s wrong when they affect how we evaluate people.”

Langeslag agreed with her assessment.

“Both men and women have those stereotypes, so this is a society-wide problem,” she said. “We need to not let stereotypes influence our judgements so that everyone can be the best version of what they want to be.”

There isn’t one catchall solution, but Urry believes there a number of things that can help.

She suggests women in STEM mentor other women and network. Additionally, they should “own their ambition,” prepare an elevator pitch about themselves and their research and insist on being credentialed properly in professional settings. STEM leaders should also work to learn about bias and to validate female colleagues and peers.

Alyssa Specht and Jazlen Rice, both juniors majoring in psychology, enjoyed the event. Rice was motivated to attend because Langeslag is her advisor.

“I just think she’s an awesome scientist,” she said. “She’s really inspiring to me.”

Rice found it informative and said she would be interested in attending another presentation on the subject. She also stressed that these discussions are beneficial for STEM fields as a whole.

“Even though this is called Women in Science, it’s actually inclusive of men and minorities as well,” she said. “It’s to help us all change as a culture.”

Specht said she was previously aware of the issues Urry addressed but believes it’s an important topic that should be talked about more. She also said she would take away one of Urry’s suggestions – practicing positive daily affirmations about her work to be more confident in the future.

“That’s just a little thing that you don’t really think about that much,” she said.

Langeslag has seen things change during her career in STEM but a lot of work still needs to be done.

“It’s just that the change is too slow,” she said. “At this rate, the question is, ‘Is this ever going to be resolved?’ Times are definitely changing and a lot of stuff is getting better. But we’re not there yet.”