Students from UMSL and the Technical University of Dortmund toured the Ruhr Museum in Essen, Germany, last month as the UMSL students visited Germany as a reward for their winning collaboration in the Future of My City Project competition. (Photo courtesy of Liz Gerard)

Liz Gerard and her classmates were excited to soak up their surroundings late last month as they strolled through the streets of the Unionviertel neighborhood of Dortmund, Germany.

The former industrial area – once home to steel manufacturers and breweries in the late 19th and early 20th Century – has been revived over the past decade as a creative quarter for artists and students located just over 3 kilometers west of Dortmund’s city center.

It is now home to a growing number of cafés, pizzerias and bars as well as restaurants and shops owned by members of the city’s sizable Sri Lankan community.

“It was really amazing to get a firsthand look at how the city’s changing,” Gerard said.

She and her fellow graduate students at the University of Missouri–St. Louis had been hearing and reading about all the transformation since last winter when they enrolled in an independent study course overseen by Todd Swanstrom, the E. Desmond Lee Professor in Community Collaboration and Public Policy Administration.

The course had them teaming up with counterparts at the Technical University of Dortmund on the Future of My City Project, created as part of the Year of German-American Friendship (Deutschlandjahr USA) to bring together students from Germany’s Ruhr Valley with students from the American Rust Belt to work on topics related to the economic, urban and social development of their communities. The project aims to help them get actively involved in planning the future of their respective geographical regions.

The UMSL and TU Dortmund students explored the gentrification debate in so-called legacy cities – older, industrial urban areas that have faced population and job loss that has contributed to high residential vacancy.

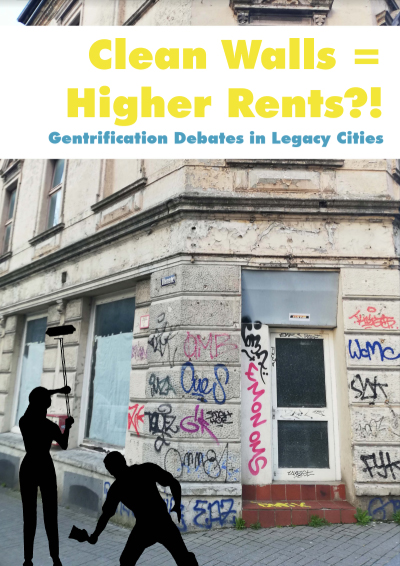

Students from UMSL and TU Dortmund compiled their research into a magazine titled “Clean Walls = Higher Rents?! Gentrification Debates in Legacy Cities.” (Screenshot of magazine cover)

The students conducted both qualitative and quantitative research and arrived at some policy solutions, all of which they compiled in a 42-page magazine. The finished product – titled “Clean Walls = Higher Rents?! Gentrification Debates in Legacy Cities” – earned them a tie for first place in the competition out of 19 groups comprised of students from 13 universities.

“I was very proud of them,” Swanstrom said. “It was just great. It’s hard to collaborate and boil all this stuff down into one little magazine after doing all this work. The magazine represents probably 5 percent of their research.”

Swanstrom had left the structure of the project open-ended when he was recruiting students. Ultimately, he got nine on board – Master of Public Policy Administration students Gerard, Adam Brown, Jodie Lloyd and Julia Spoerry; political science master’s students Nathan Theus and Chancelor Thomas; political science doctoral student Liz Deichmann; education psychology doctoral student Mark Kasen; and Sydney Gosik, pursuing a master’s degrees in public health and social work at Washington University in St. Louis.

“It’s the first independent study I’d ever done,” said Lloyd, who works as a senior analyst in the Office of the Executive Vice Chancellor for Administration at Washington University. “Being in that small group setting and focusing on just one particular project was interesting from the subject matter but also from the whole project management level.”

The nine St. Louis students split into three groups – the Quals, the Quants and the Pols – focusing on qualitative research, quantitative research or coming up with policy solutions.

They examined changes – and the attitudes of people to those changes – in five evolving St. Louis neighborhoods: Benton Park, just west of Soulard; Botanical Heights, which has been rebranded from its former name, McRee Town; Forest Park Southeast, including what is now commonly referred to as The Grove; and the Jeff-Vander-Lou and St. Louis Place neighborhoods northwest of downtown near the site of the new National Geospatial Intelligence-Agency West campus.

Any talk of “gentrification” evokes thoughts of trendy neighborhoods experiencing rising rents in major cities such as New York, Boston and Berlin. The word typically conjures negative thoughts among longtime residents who find themselves pushed out by the increased cost of living.

Quantitative data – including the assessed property values, residential sales and the poverty rate – shows that significant displacement has not accompanied the changes occurring in the St. Louis neighborhoods, some of which were confronted by problems of vacancy before the recent investment. Rents in the neighborhoods have remained relatively affordable.

But, as the students learned through focus groups with local residents, man-on-the-street interviews and conversations with elected officials and police officers, concerns about what might occur still exist.

“One of my primary interests is what’s happening in North St. Louis, with regard to NGA moving in,” said Kasen, who hosts a local radio show called “Something’s Happening” on TalkStl.net. “I was not surprised by the fact that the members of the community are very sharp and up-to-date on what the potential problems will be that they may face. They have huge suspicions.”

In many cases, people still welcome the byproducts of reinvestment.

Theus talked specifically about the attitudes he encountered in Botanical Heights, which local residents told him had come to be known colloquially as “New Jack City” because of the recurring problem of car thefts that used to occur in the neighborhood.

“If I had to summarize everyone’s feelings of it, the older residents – older white and older black residents – who live on the west side of town, which hasn’t been remodeled by the developers yet, they see gentrification as both a mix of good and bad,” said Theus, who finished his master’s last spring and is now exploring a career in the foreign service. “They see it as a potential bad that it could pressure other people out of the area. But they see it as good because the gentrification forces, if you will, forced positive change in their neighborhood, i.e. more economic development, new people moving in, lower crime, beautified streets. They recognize that the old neighborhood was dilapidated, crime-ridden and likely not good to live in.”

There are concerns that development be equitable, particularly with too many parts of the city struggling with disinvestment. African Americans, in particular, also tend to desire historical recognition of how these changing neighborhoods were first created.

Their counterparts in Germany conducted their own research on neighborhoods that have undergone recent transformations in Dortmund, and the magazine the students produced compared and contrasted the data they collected in the two cities.

The two groups participated in a series of Zoom conferences throughout the project to discuss their findings. One thing the German students didn’t understand was their American counterparts’ instinct to consider race as a data point for investigation. It was perhaps the most significant of the cultural differences that exist between St. Louis and Dortmund.

Graffiti art adorns a concrete wall in one of the changing neighborhoods of Dortmund, Germany. (Photo courtesy of Liz Gerard)

When coming up with policy solutions to ensure neighborhood change doesn’t harm existing residents, the students tried to put forward proposals that could work across cultures. High on that list was inviting input from the people already living in those areas.

“That’s something in my professional experience that I really believe in – that the more you can get people who are affected by neighborhood change involved in the process of what’s happening, the more equitable it’s going to be,” said Brown, a planner who works for the City of University City. “Also, it’s more sustainable in the long term because you have buy-in and you have the enthusiasm and the energy and the spirit of the people who live there.”

The students spent days designing and editing their magazine and submitted their edited work near the end of May. They learned they were chosen one of the co-winners in July.

A part of the prize for their success was the trip to Germany that Gerard and seven of her fellow students in St. Louis made to Dortmund in late October.

They got to meet with the students they’d talked to over email and Zoom for so many months last spring and toured the neighborhoods in Dortmund as well as the city’s soccer stadium. They also talked to professors about policies that have led to neighborhood change there.

“I was surprised that the government plays a more active role in the development of low-income housing,” said Gerard, who works with the U.S. Bank Community Development Corporation. “Compared to the United States, private investors have a more limited role. In the States, we have programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit and Historic Tax Credits to incentivize the development of low-income units and historic preservation. Those programs don’t exist in Dortmund.

“I also think there is better collaboration between public and private actors in Dortmund, compared to the fragmented St. Louis economic development model.”

Swanstrom and the students in St. Louis will get to serve as guides for their German counterparts later this week when the Dortmund students visit St. Louis for four days beginning Sunday.