Counter clockwise from top left: University of Missouri–St. Louis students Luke Lauter, Ngoc Nguyen and Rachel Gabrian along with Assistant Teaching Professor and Community Engagement Coordinator Rob Wilson hold up a tourism banner the group designed on the behalf of the census-designated area Spanish Lake. The three students were four of 12 in Wilson’s “Where We Live” community engagement class last semester. (Photos courtesy of Rob Wilson)

Grace Morrow, Sophie Loban and Ngoc Nguyen are in complete agreement about the best part of spring semester at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

Getting out of the classroom.

The trio – along with nine classmates – did so as part of the Pierre Laclede Honors College class “Where We Live,” taught by Assistant Teaching Professor and Community Engagement Coordinator Rob Wilson.

Wilson, who first debuted the course in 2011, examines two St. Louis communities per semester, focusing on the relationships between historic resources and present-day environment. He breaks the class into two groups to work on problems identified by community leaders.

The class partnered with the Missouri communities Spanish Lake and University City last semester, and Wilson both brought the leaders into the classroom and sent his students out to Spanish Lake and University City.

“The tours were cool,” said Morrow, who worked with Spanish Lake. “Going and getting out and seeing everything and listening to them explaining their city, you could see them light up.”

That Morrow, Loban and Nguyen appreciated experiencing the communities firsthand demonstrates how well they got the point of the class.

“Getting them outside the classroom walls is my big goal here,” Wilson said. “Sometimes students don’t understand the implications of what we’re teaching. Getting them out of the classroom helps them understand the importance.

“The best part about community engagement is the satisfaction students have after it’s over. They really feel like they make a difference, a sense of purpose. I can sit there and teach in the classroom, but it’s different to see what they create and how it impacts where they live, work and play.”

For each class, Wilson chooses two communities with differing histories and challenges. The students treat the communities as clients and, after a consult with leadership, agree upon projects to work on for the remainder of the semester.

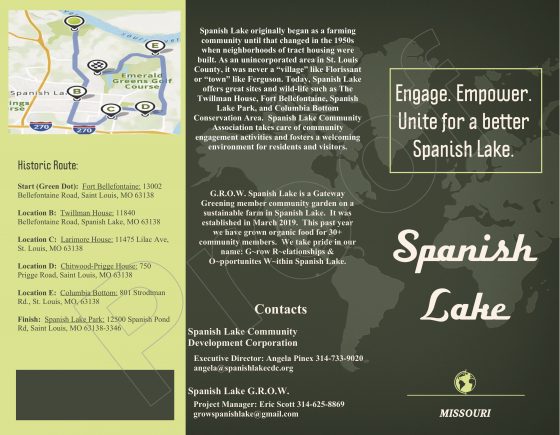

Spanish Lake, a census-designated place in St. Louis County, is unincorporated and, because of that, has less resources to work with than cities with a tax base. Angela Pinex, the executive director of the Spanish Lake Community Development Corporation, explained that one of their biggest needs was changing perceptions.

“We needed something conducted that changed the narrative about the community because when someone hears about North County, the first thing that comes out of the top of mind is crime,” Pinex said, explaining that there had also been a negative documentary about Spanish Lake that came out in 2014.

That need spoke to Nguyen. She noticed the passion of everyone who worked at the Spanish Lake CDC but didn’t feel the same sense of cohesive community when driving around.

“Spanish Lake just popped out a lot more for me, knowing that the community needed a lot more in terms of funding and engagement,” she said. “We designed banners to hang, a brochure for the community to hand out. It gives us hope that the community would come to realize that Spanish Lake is a wonderful city and that they should cherish that.”

Pinex and the Spanish Lake CDC were also hoping for a video of their own – one that could help counteract the negative effects of the documentary. Morrow, a communication major, put one together.

She was drawn to Spanish Lake because a close family friend – Morrow’s honorary “aunt” – lives there and was able to give Morrow extra insights about the community.

“The documentary didn’t even talk about the historical value of Spanish Lake,” she said. “We hit on that and the conservation area and wildlife, the Zoo moving there. Also, that these are people’s homes, and they do love Spanish Lake, and they’ve been living there for years. So, people can see the potential that Spanish Lake has and what it already does have.”

Though University City has a completely different history and set of challenges, some of the solutions were similar.

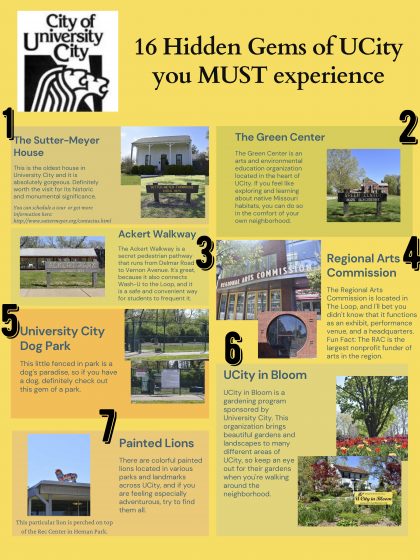

Loban, who lives in University City, embarked on cataloguing the unknown facets of the city for her project, 16 Hidden Gems of University City. She was already passionate about her hometown, but the experience opened her eyes to what she’d been missing.

“There was a lack of the residents in seeing what they have,” she said. “The resources and the beauty and the parks and the infrastructure and community that they actually have. For example, we have a farmer’s market, and I didn’t even know about it. There’s an African market, and it’s home to what’s basically the Chinatown of St. Louis. I feel like a lot more people could do with the knowledge that there are such cool, unique things that are either in walking distance or five minutes away from where they live.”

Learning about the intricacies of the city, such as the lack of tax revenue from properties owned by nonprofits in the loop or what tax incremental financing will mean for some businesses on Olive, was fascinating to Loban.

Though the class normally ends with a presentation of the projects to the community leaders in person, that wasn’t possible last semester with the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Instead, the students presented over Zoom at the end of term and then, in late June, as stay-at-home orders relaxed, brought the printed banners and pamphlets to the communities in person.

The results were felt deeply.

“We loved it,” Pinex said. “What they were able to do in such a short time, just a number of months… We’re looking forward to possibly working with the Honors College again.”

The effects of the students’ works weren’t only apparent for the recipients but also on the makers as well.

Nguyen, a mechanical engineering major, felt the experience made her more conscious of how some engineers have failed Missouri historical, especially in regard to the sewage system in St. Louis.

“It made me think that as an engineer, part of your purpose is to serve society,” she said. “You shouldn’t be acting in a way only to profit yourself. It made me reflect a lot upon what I want to do with my degree or what I want to do in my career.

“It made me want to be more active, going to community meetings, making sure that our voices are heard. Even if I’m not working within infrastructure, I will still be actively participating in other means.”

Loban, who’d come into the semester a vocal performance major, ended up adding an urban studies minor.

“I didn’t really have a sense of direction, but in this class, I realized I had a passion for learning about the city and working in the community,” she said. “I really liked seeing what people were doing to help their city.

“I realized that I don’t want to be that person on stage getting all the attention. I want to be the person behind the scenes, getting to know people, making relationships and connecting people with other people. When I finally came to that realization, I was like, ‘I need to do something with this. This is my passion.’”