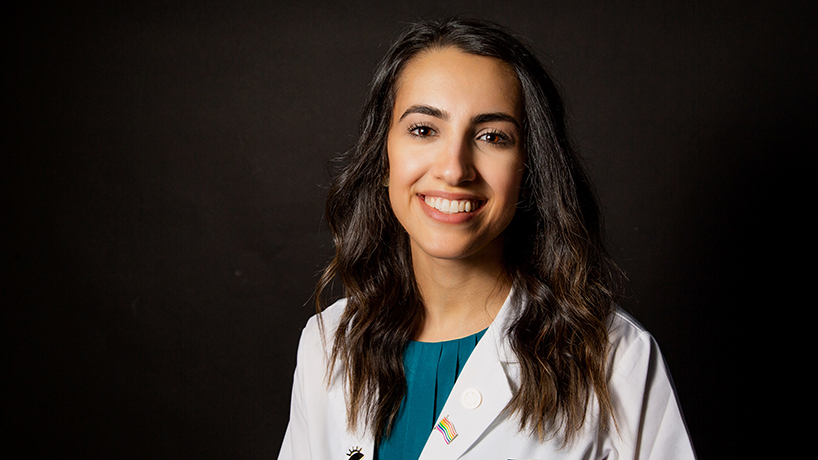

Delaram Shirazian launched her Instagram account, Humaneyezing Healthcare, about six months ago. The College of Optometry alumna hopes to use it to bring light to doctor-patient communication. (Photo courtesy of Delaram Shirazian)

The patient came in for a follow-up during Delaram Shirazian’s clinical rotation at Affinia Healthcare. He’d been to the clinic before, and his optometrist had wanted him to return for a glaucoma assessment.

He didn’t come back for a few years – much too long.

“He had lost a significant amount of vision due to glaucoma,” the University of Missouri–St. Louis alumna said. “You realize that not only is it challenging to take care of patients that only have you as a resource, but there’s so many other factors involved in care as well.

“Your mind goes, ‘Did we not educate this patient enough? Did they not understand the severity of the situation?’ That patient really stuck with me as someone that I wish we would have been able to help.”

When she thinks back to school, that patient flashes to Shirazian’s mind, as does another – one who’d come in with headaches and vision loss and was successfully referred to another provider in the same building.

The two experiences underscored the importance of community care, especially for underserved populations, and doctor-patient communication for Shirazian, and since graduating with her OD in 2016, she’s remained focused on those interests.

After graduating from the UMSL College of Optometry, she completed an ocular disease and low vision rehabilitation residency at the Kansas City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, going on to teach at the State University of New York College of Optometry. Then, this year, she launched Humaneyezing Healthcare, an Instagram page that combines those interests with research and lived experiences as a practitioner.

“In school, we spend a lot of time studying diseases, medication, pathways, etc.,” Shirazian said. “But we don’t spend a lot of time thinking about, ‘How am I going to educate the patient on their condition? How am I going to make sure that they’re taking their medication? How am I going to gain their trust and develop rapport with them?’

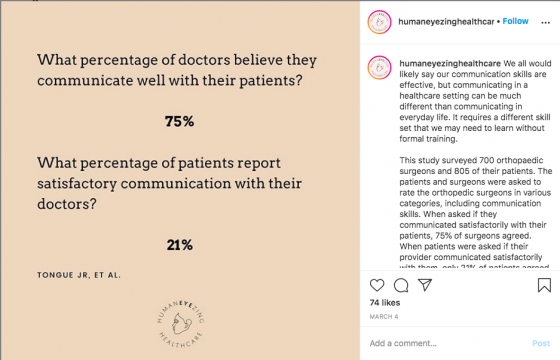

“I stumbled upon this path and have done a lot of research in the past three years. I decided to share my research with the health-care community in hopes that the goal of humanizing health care will inspire people to want to work on the art of doctoring as well as on the science of doctoring.”

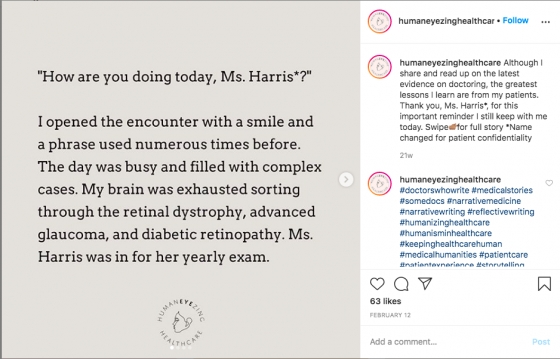

The information she shares ranges from fact snippets to quotes to experiential and more.

In her third post, Shirazian posed a question: How long does it take a provider to interrupt a patient? Answer: 11 seconds.

Another is a snippet from an article by Dr. Michelle M. Kittleson, quoted from The New England Journal of Medicine, about feelings of regret after a challenging communication with a patient.

There’s also a drawing from a young patient illustrating an examination room. The doctor is in the corner of the room on the computer, facing away from the patient and family. In the post, Shirazian writes about the pros and cons of electronic record technology and how it affects doctor-patient interaction.

Though she’s just getting started, her efforts are already having an impact on her colleagues and students – even on doctors outside the field of optometry.

“I hope that it inspires practicing providers to really examine the patient-doctor relationships and how they’re taking care of their patients,” she said. “As an educator, I really hope that it inspires our educators and our medical and health-care professional schools to want to pay more attention to this in school. And not as a side project for their students to learn on their own, but as something that we teach.”

Shirazian already has started to do just that and, with another optometrist, teaches a course on the art of communication. She also hopes to have an effect by continuing to grow the account, doing research and starting to write on the subject.

A St. Louis native, Shirazian comes by her interest in communication and equitable patient care partially due to her background.

“I am very interested in underserved populations,” she said. “I’m a first-generation college student and also from an immigrant family. So some of it was personal. I knew firsthand what it was like to not have health insurance or not to have all of the health-care benefits that maybe most people have in this country, and I realized that someone’s ability to pay shouldn’t reflect on the quality of care that they receive.”

She’d entered as an undergraduate interested in medical school, but at some point in her studies something undefinable changed, and Shirazian began to doubt that career path. Then, while shadowing an optometrist, she found herself drawn to the depth of the relationship the doctor had with patients.

She chose UMSL’s program in part due to the small class sizes and individualized attention. During the final year of optometry school, when students rotate through several different clinical placements in order to gain experience for their future practices, Shirazian primarily selected community-focused experiences.

She rotated through Affinia Healthcare in downtown St. Louis City, People’s Health Center in University City, Missouri; and a community health center in Carondelet, Missouri.

She felt those experiences and her education at the Patient Care Center on UMSL’s campus prepared her well for her residency and then for life after school.

“We trained a lot clinically, and we’d see patients who hadn’t received comprehensive care every year and sometimes they would come in with complex conditions or really advanced diseases,” she said. “UMSL did a really good job of preparing us for those encounters. After graduating, I remember reflecting on a lot of those encounters in the community health clinic and realizing I had learned so much about disease. I actually learned a lot more about people and taking care of patients, just as much as I did about the technical doctor stuff.”