Turn the Page STL and the University of Missouri–St. Louis’ Community Innovation and Action Center joined forces to explore the root causes of literacy barriers in the region in 2020. They subsequently developed the Turn the Page STL 2021-2023 Strategic Plan, which aims to improve literacy rates for children from birth through third grade in seven school districts located in the St. Louis Promise Zone. (Main photo by August Jennewein, others courtesy of Turn the Page STL)

Recent data suggests too many students in the St. Louis region face challenges developing literacy skills. Furthermore, inequalities related to race and socioeconomic status are replicated in literacy.

In light of those realities, Turn the Page STL and the University of Missouri–St. Louis’ Community Innovation and Action Center have joined forces to increase the number of children reading at or above grade level by the end of third grade in St. Louis communities.

Last year, the two partnered to explore the root causes of literacy barriers in the region through a racial equity informed lens. They examined publicly available data and gathered feedback from more than 100 St. Louis organizations, educators, administrators and families.

The organizations took that research and authored the Turn the Page STL 2021-2023 Strategic Plan, which aims to improve literacy rates for children from birth through third grade in seven school districts located in the St. Louis Promise Zone – an area that includes parts of north St. Louis city and north St. Louis County that have seen disinvestment or neglect.

“There’s been a compounding of injustices that have led to Black and brown children not having the same opportunities and the same resources to learn and to have those skills,” said Kiley Bednar, CIAC’s interim co-director. “It’s a social justice issue to try to mitigate that and address that in a variety of ways, not just through school districts but through community connections, through policy change and through taking a comprehensive approach.”

Bednar first connected with Turn the Page STL in the summer of 2019 when Lisa Greening was starting the organization as a St. Louis chapter of the Campaign for Grade-Level Reading.

Greening, project director, had previously worked with Ready Readers, another literacy advocacy organization. However, Turn the Page STL differs in that it was designed to be a collective impact initiative involving a broad coalition of community stakeholders.

At Bednar’s suggestion, Greening pursued a Chancellor’s Certificate in Community Partnerships and Coalition Leadership, which offers aspiring and current community partnership leaders training in necessary competencies and skills. After earning her certificate, Greening started working on the Strategic Plan.

She and other members of Turn the Page STL collected data over the course of 2020.

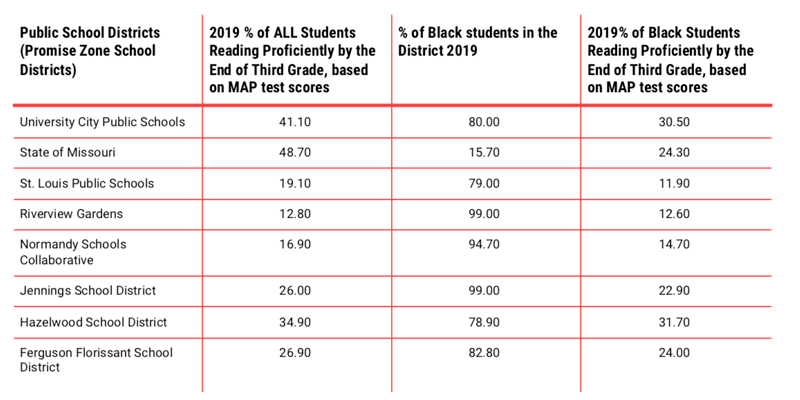

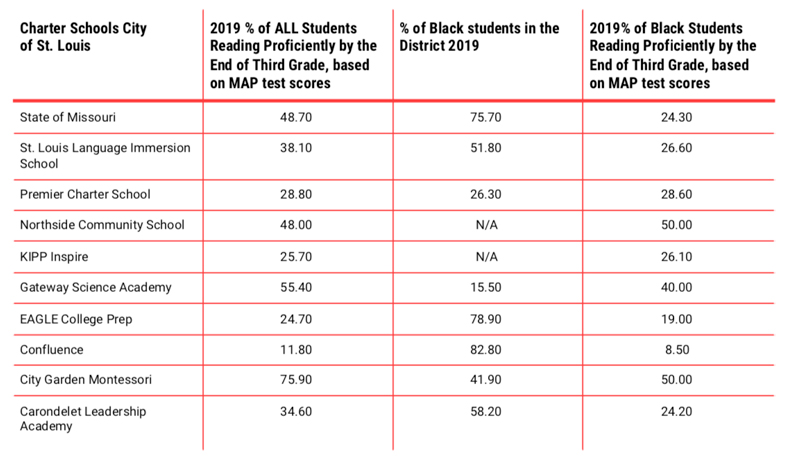

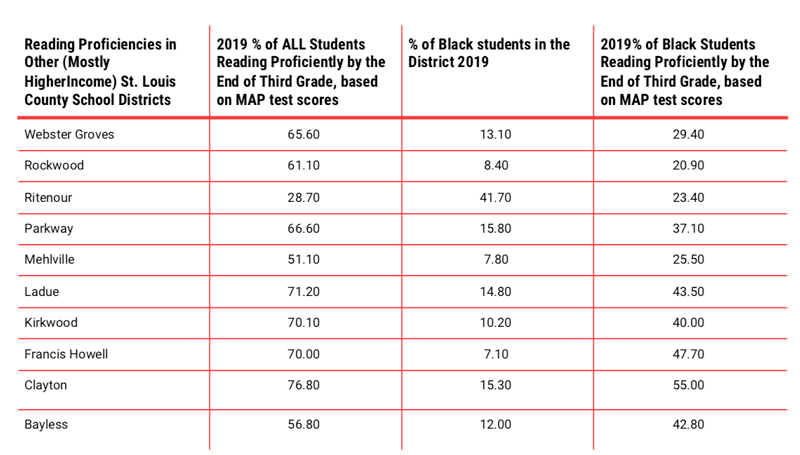

They reviewed Missouri Assessment Program scores in third-grade reading proficiency from Promise Zone public school districts, higher-income St. Louis County public school districts and city charter schools; data from other GLR Campaign chapters; and academic literature.

Additionally, CIAC partnered with Turn the Page STL to facilitate eight focus groups and many one-on-one sessions with educators and families. The organization also helped analyze the resulting feedback.

The stark literacy gaps in St. Louis began to show while compiling the data.

“What became very apparent in the St. Louis community is that it is a racial inequity issue,” Greening said. “Our Black and brown kids across the board, whether they’re in a low-performing district or a high-performing district, have less reading proficiency.”

The report notes that, with a small number of exceptions, a higher percentage of Black students attending a Promise Zone school district closely correlates with lower performing third-grade reading proficiency scores.

While the numbers improve at some city charter schools and wealthier St. Louis County school districts, the percentage of Black students reading proficiently compared to classroom peers is still lower. For example, in the School District of Clayton, nearly 77 percent of students read proficiently by the end of third grade in 2019. The number dropped to 55 percent for the district’s Black students.

The data supported the understanding that racial inequity in the St. Louis region has contributed to disparities based on race and zip code, and CIAC and Turn the Page STL crafted the strategic plan with that in mind.

Feedback from the focus groups paralleled these findings.

Greening said, over and over, educators pointed to systemic racism, which has led to inequities in the region’s schools. Over several generations, education systems funded by personal property taxes have left schools in disinvested communities with less and less funding for teacher salaries and basic classroom resources.

“We heard about trauma, not only for families but for teachers working hard, administrators working hard,” Bednar said. “So often it’s easy to blame this group of folks or this group of folks, but it really is a systemic issue in terms of how our education is funded. That impacts both those who are working to teach, as well as children and families.”

She added that families pointed to stress and fatigue at home. Many are in “survival mode” with hectic schedules – sometimes with parents working two or three jobs. It leaves little time or energy for reading at home. Greening noted lack of trust is also an issue, which becomes a barrier to building relationships between families, educators and other community members.

“We kept hearing families say, ‘I don’t trust this after school program. I don’t trust the library because they say they’re fine-free, but I owed 20 years ago, and they still won’t give me a library card. I don’t trust my schools. All they do is tell me how my kid is doing poorly,’” Greening said.

After reviewing all of the data and community feedback, Turn the Page STL and CIAC identified five strategic priorities to make change: Kindergarten readiness, summer and out-of-school learning, family engagement, teacher preparedness and community awareness.

Turn the Page STL has formed work teams to tackle each priority, and they plan to do so through a variety of initiatives:

- Research a community-based “Reading Captain” model pioneered by Philadelphia’s Read by Fourth organization

- Provide science-based, culturally competent literacy education for teachers

- Support the work of local literacy programs and early childhood centers and schools through alignment and resources

- Work with public and private sectors to professionalize early childhood educators

- Give both families and educators a voice about literacy in a community awareness marketing campaign

- Advocate on behalf of families for quality education

- Inform and share information about the factors that contribute to reading proficiency

The work teams will collaborate with the St. Louis Regional Data Alliance to set baseline data and track outcomes through a proprietary dashboard. Greening said the goal is to increase reading proficiency by the end of third grade for students in Promise Zone school districts by 10 percent by the end of 2023.

Bednar and Greening are aware that moving the needle on literacy education can be a slow, methodical process – but it’s one that’s imperative.

“Childhood literacy is connected to a range of outcomes throughout a lifetime,” Bednar said. “If children are proficient at reading by grade three, they’re more likely to graduate from high school. It’s also connected to being a literate citizen in terms of being in a democracy and being connected to social participation and being able to navigate many of the things we’re dealing with when it comes to elections. It’s not just about third grade. It’s really about a lifetime of literacy.”