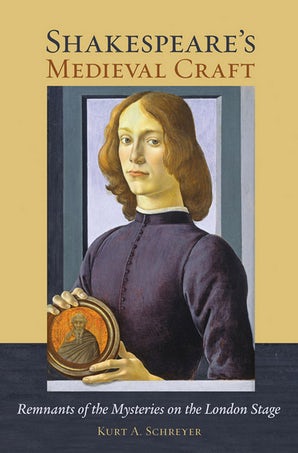

Sotheby’s, a renowned international auction house, cited Associate Professor Kurt Schreyer’s 2014 book, “Shakespeare’s Medieval Craft: Remnants of the Mysteries on the London Stage,” as an authoritative source on the Sandro Botticelli portrait. Schreyer’s book reexamines the link between the late Middle Ages and Renaissance works, such as William Shakespeare’s plays and Botticelli’s paintings. (Photo by August Jennewein)

In January, Kurt Schreyer’s brother texted him a link to an article about a record-setting art auction.

Sandro Botticelli’s painting, “Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel,” had just sold for $92.2 million at Sotheby’s. It was the highest price ever paid for an Old Masters painting. Schreyer’s brother isn’t an art buff, but he did recognize the painting from the cover of Schreyer’s book, “Shakespeare’s Medieval Craft: Remnants of the Mysteries on the London Stage.”

Curious about the sale, Schreyer started perusing the Sotheby’s website and received a shock.

Kurt Schreyer’s book, “Shakespeare’s Medieval Craft: Remnants of the Mysteries on the London Stage,” explains that the round object in the portrait is actually a Medieval remnant that was not painted by Sandro Botticelli. (Cornell University Press)

“I was wondering whether I would find some of the scholars I knew from my own research in Sotheby’s list of academic references,” he said. “Sure enough, there they were, and then my eye caught my own name.”

Sotheby’s cited his book as an authoritative source on the Botticelli portrait. Schreyer, an associate professor of English at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, is quick to note that he is not an art historian, but he was honored nonetheless.

“It felt like a great recognition, and after all, I was able to offer my opinion, my scholarly reading such as it is, of the painting,” he said. “I think, humbly, it’s a deserved citation, but it was a great surprise because I’m a literary scholar.”

Schreyer teaches courses on William Shakespeare and early English drama. However, his academic interests and research extend beyond the Bard of Avon. He has also studied the link between the late Middle Ages and Renaissance works, such as Shakespeare’s plays.

He first became interested in the subject as an undergraduate when a professor theorized that the pre-Reformation English drama had a greater influence on Shakespeare than it had ever been given credit. The idea stuck with him as he continued on to graduate school and a career as a literary scholar.

Eventually, it led to the release of “Shakespeare’s Medieval Craft: Remnants of the Mysteries on the London Stage” in 2014. The book reexamines Shakespeare’s relationship to the culture of the late Middle Ages.

“We often like to hold up Renaissance authors as people that define their age,” Schreyer said. “Think of Shakespeare but also think of Da Vinci, think of Botticelli. There’s a tendency to wall them off in their own time period in the Renaissance and say they were a Renaissance painter, author or artist. In fact, the book is arguing that if you look more closely at their work, their paintings, their plays, you can see influences from the previous age – not just influences but that there’s a deep reference.”

Schreyer noted that there are specific works of the late Middle Ages that inspired Renaissance artists and authors. As he was finishing his book, he came across Botticelli’s “Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel,” a painting that perfectly exemplifies that idea.

Botticelli painted several portraits of young men holding round objects, such as a medal. However, the painting in question hides a secret that most onlookers wouldn’t think twice about.

“Here’s the thing about this particular painting, if you look at it closely at the round object, it looks as if Botticelli just painted that round saint figure,” Schreyer said. “He didn’t. The painting is on a wooden panel, and he actually carved out a space in the panel so he could insert a Medieval remnant of a Medieval painting – probably an altarpiece – that had this saint figure in it. He stuck it into this portrait. When you have that, you have a Renaissance artist building his modern work around the Medieval object.”

The portrait perfectly illustrated the argument of the book, which is why Schreyer featured it on the cover and discussed it in the first chapter.

Schreyer is excited that the high-profile sale has brought attention to such a distinctive piece of art. He also feels lucky to include himself among those Sotheby’s cited.

“I was just humbled and thrilled to be included in that group of scholars,” he said, “for this really fascinating unique art object.”